Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2005-06 | Foreword

Foreword

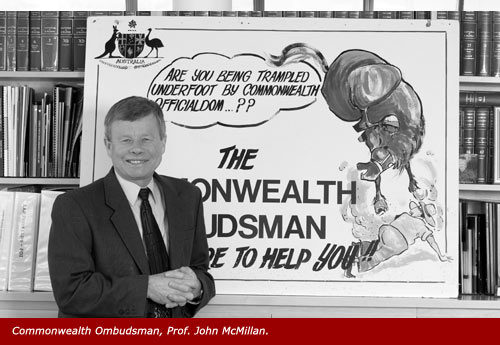

A foundation task of the new Commonwealth Ombudsman office in 1977 was to make itself known and understood by Australians. One amusing way of doing this was with billboards that invited people to contact the Ombudsman if they were being 'trampled underfoot by officialdom', 'strangled by bureaucratic red tape', or were having their problems 'swept under the carpet'.

Those stereotypes of government are still with us, but the situation of the Ombudsman's office has changed markedly. This annual report contains many examples of the constant growth, adaptation and maturation of the office.

An outward change is in the structure and appearance of the office, which now wears the hats of seven Ombudsman roles—Commonwealth Ombudsman, ACT Ombudsman, Defence Force Ombudsman, Taxation Ombudsman, Immigration Ombudsman, Postal Industry Ombudsman, and Law Enforcement Ombudsman. That change in structure was explained in the foreword to last year's annual report. Government and the public now expect an oversight agency to have both a generalist role that covers most functions and problems in government, as well as a specialist understanding and distinctive profile in some areas being monitored.

The cascade of 'Os' on the cover to this year's annual report depicts this change in the office and its diversity of functions.

An area of important change is immigration oversight. This is a traditional function of the office, but now with specialist functions and activity in the combined role of Commonwealth and Immigration Ombudsman. One new function is to prepare a report on each person held in immigration detention for more than two years. During 2005–06, my office finalised 66 reports that were tabled in the Parliament, with many more in preparation. This reporting role is a new type of function for an Ombudsman's office, and has required us to develop a format for examining and reporting on each case after consultation with the department and the person in detention. The function has also provided an opportunity for the office to demonstrate that the underlying Ombudsman values—independence, impartiality, integrity, accessibility, professionalism and team work—can suitably be adapted to a range of different oversight tasks.

The more active role of the office in immigration oversight has occurred in other ways. Among them are the investigation of 248 individual cases referred to the office by government; participation in the department's newly-established committees to provide advice on training, detention health, and values and standards; and the instigation of new own motion projects on matters such as complaint handling, notification of review rights, and compliance operations.

The new role of Postal Industry Ombudsman (PIO) poses a challenge of a different kind. The PIO jurisdiction extends to private postal operators that are registered with the PIO scheme, as well as Australia Post. It is a new step for the office to develop an Ombudsman scheme covering both public and private sector bodies. The core principles of good complaint handling and administrative investigation apply equally to both, but there are differences. The criteria for administrative deficiency are not identical, reflecting the fact that private sector functions are commercial and not statutory in nature. There is also a different method for classifying the investigation of complaints, since the cost of investigations is charged to the participants in the scheme.

Private sector activity also comes under the scrutiny of the Commonwealth Ombudsman through a recent amendment to the Ombudsman Act 1976 that confers jurisdiction over Commonwealth service providers. My office can now investigate complaints about government contractors providing goods and services to the public under a contract with a government agency. This extended jurisdiction confirms the role the office has long played in dealing with complaints that arise within immigration centres and the Job Network. The jurisdiction is also important to oversight of the Welfare to Work program, which incorporates a large role for private sector bodies in activities such as job referral, job capacity assessment, and financial case management.

The other new Ombudsman role to be developed during 2006–07 is that of Law Enforcement Ombudsman. This again is a traditional function of the office, to be modified under a new statutory framework for dealing with complaints and conduct issues in policing. The Ombudsman retains a complaint investigation function (notably for serious conduct issues), but will otherwise play a more active role in oversighting and auditing the way policing agencies handle complaints and conduct issues. This monitoring and auditing role adds to the office's existing (and growing) function of inspecting the records of law enforcement agencies to examine their compliance with statutory controls applying to telecommunications interception and access, electronic surveillance and controlled operations.

These and other changes in the work of the office have fed into a general review of methods and operations that commenced in the last reporting year and was completed in 2006. Innovations that are described in this report include the establishment of the Public Contact Team as the first point of contact with the office; the introduction of a new complaints management and recording system; the conduct of an active outreach program, especially in rural and regional Australia; and more active engagement with other public sector and industry ombudsman offices to share experience and initiate research projects.

Individual complaint handling across all areas of government remains the core function of the office. In 2005–06, we handled over 17,000 individual approaches and complaints that were within jurisdiction. Those figures alone demonstrate the need for a vibrant Ombudsman's office to which people can turn with unresolved problems and grievances about government agencies.

Another side to those complaints is that they shed light on newly emerging problems within government; some problems transcend the responsibility of individual agencies but nevertheless arise within government. This and previous annual reports have drawn attention to those issues in the chapters on 'Problem areas in government decision making', 'Challenges in complaint handling' and 'How the Ombudsman helped people'. The complexity of legislation and government programs, and the complications that poses for members of the public, is one such theme taken up in this report. Another is the importance of internal complaint handling in agencies and the Ombudsman's role in externally scrutinising that activity.

This period of change and growth in the Ombudsman's office (staff numbers have risen from 82 in 2003 to 146 this year) has been possible and seamless only through the professionalism and commitment of the staff. They have continued efficiently to resolve tens of thousands of individual approaches and complaints, while developing new roles, activities and work practice methods. The total staff commitment has been displayed in many ways, ranging from the 100% staff voting approval of a new certified agreement to the voluntary effort of many staff to befriend and play host to many visitors from Asian and Pacific ombudsman offices. Together with my two Deputy Ombudsmen, Ron Brent and Vivienne Thom, I would like to acknowledge the key role this staff effort has played in the work of the office over the past year.

John McMillan

Commonwealth Ombudsman