Chapter 6 | Promoting good administration | Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2006-07

CHAPTER 6 | Promoting good administration

Introduction

A core objective of an ombudsman’s office is to move beyond the individual problems highlighted in individual complaints, and to foster good public administration that is accountable, lawful, fair, transparent and responsive.

An individual complaint may highlight issues that are systemic in nature, such as the provision of inadequate or misleading advice on a particular aspect of government service delivery, or the application of a policy that is inconsistent with an agency’s governing legislation.

An issue that arises in an individual complaint about a specific agency may open a window onto similar issues in other areas of government administration.

Through thirty years of experience in dealing with individual complaints, the Ombudsman’s office has built a broad base of knowledge about government administration and the ways in which good, and poor, administration can have an impact on people. We draw on this experience to promote improvements in public administration through a variety of mechanisms.

‘An issue that arises in an individual complaint about a specific agency may open a window onto similar issues ...’

This chapter discusses some of the ways the Ombudsman’s office has promoted good administration. We made submissions to a number of parliamentary and other government inquiries. We also initiated or participated in projects that aim for systemic reform in areas such as the use of automated decision making and protection of internal whistleblowers. Own motion investigations undertaken by the office are described in other chapters, and briefly noted in this chapter. Cooperation with other oversight agencies, and with Ombudsman offices in Australia and the Asia-Pacific region, enables joint projects to be undertaken, best practice experience to be shared, and a mutual support network to be developed.

Submissions, reviews and research

Parliamentary committees and submissions

The Acting Ombudsman and staff made a submission and appeared before the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee concerning its inquiry into the provisions of the Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Veterans’ Affairs Legislation Amendment (2006 Budget Measures) Bill 2006. The Bill, which was not enacted, would have given significant new search and seizure powers to Centrelink officers.

We made a submission to the same committee, and appeared before it, in relation to its inquiry into the provisions of the Crimes Legislation Amendment (National Investigative Powers and Witness Protection) Bill 2006. Our comments related to controlled operations and delayed notification search warrants.

We also made a submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services regarding its inquiry into the Exposure Draft of the Corporations Amendment (Insolvency) Bill 2007, and a supplementary submission to the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit inquiry into taxation administration in Australia. We appeared before the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee in relation to its review of the implementation of reforms to Australia’s military justice system. More details about this review are provided in the ’Defence section’ of Chapter 7—Looking at the agencies.

We provided submissions to the Australian Law Reform Commission inquiry into legal professional privilege and Commonwealth investigatory bodies, and into its review of the Privacy Act 1988.

Whistleblowing project

Our office continued its leading role in the national research project, Whistling While They Work: Internal Witness Management in the Australian Public Sector. This three-year collaborative project is the first national study of the management of whistleblowers and other internal witnesses. The project aims to describe and compare organisational experience under varying public interest disclosure regimes across the Australian public sector.

By identifying and promoting current best practice in workplace responses to public interest whistleblowing, the project will use the experiences and perceptions of internal witnesses and first and second level managers to identify more routine strategies for preventing, reducing and addressing reprisals and other whistleblowing-related conflicts.

‘The project aims to describe and compare organisational experience under varying public interest disclosure regimes ...’

During 2006–07 the project conducted three major surveys. The first survey involved the distribution of a questionnaire ‘Workplace Experiences and Relationships’ to approximately 23,000 randomly selected employees across 117 Commonwealth, New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australian public sector agencies. Over 7,600 responses were received, providing the project with a comprehensive dataset.

The second survey covered 15 public sector ‘case study’ agencies, including four Australian Government agencies. This phase involved distributing a questionnaire to employees who had volunteered (on a confidential basis) to describe their experiences of providing information about alleged or suspected wrongdoings in their workplaces. It was followed by the distribution of questionnaires to employees within the agencies, who were either specifically selected on the basis that their work role may have involved them dealing with the internal reporting of wrongdoing, or randomly selected because of their managerial responsibilities.

The third survey was directed at 27 ‘integrity agencies’ across the four jurisdictions. The term ‘integrity agency’ is used here to describe agencies that have an independent or whole-of-government responsibility to ensure and promote public integrity in their jurisdiction, with direct reference to public sector whistleblowing. This survey covered agency practices and procedures for receiving, investigating and managing reports from public sector employees about wrongdoing in the sector, and the experience of individual staff members dealing with issues and cases involving public sector employees who had reported wrongdoing.

Some data collection is continuing, and it is expected the data analysis and reporting will continue into 2008.

In addition, in November 2006 an issues paper, Public Interest Disclosure Legislation in Australia: Towards the Next Generation, written by the project’s leader, Dr AJ Brown, from Griffith University, was released. A joint foreword to the paper by the Commonwealth, New South Wales and Queensland Ombudsmen drew attention to the importance of developing a national and coherent approach to the design of whistleblower protection laws. The paper is available on our website at www.ombudsman.gov.au.

Automated assistance in administrative decision making

Australian Government agencies are turning increasingly to computer systems to automate or assist in the administration of programs. Automated systems that are properly constructed and implemented have the potential to improve the efficiency, accuracy and consistency of many government administration processes.

Our office, together with the Australian Government Information Management Office, the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) and the Privacy Commissioner, was involved in the publication of the Automated Assistance in Administrative Decision-making Better Practice Guide. The guide was jointly launched in April 2007 by the Ombudsman and the Secretary of the Department of Finance and Administration, Dr Ian Watt.

The guide was developed by the AAADM Working Group, which involved sixteen Australian Government agencies. The Ombudsman was pleased to see the cooperative approach taken in the development of the guide, with a wide range of agencies making a significant contribution to the content.

The guide aims to assist public officials understand how key administrative law and public administration principles apply to automated systems that are used to assist with administrative decision making. Transparency and accountability are particularly important in this regard, and are key components of the better practice guide. The guide includes the following key principles.

- The underlying rules contained in the automated system should accurately capture the relevant legislative and policy provisions as well as the relevant procedures.

- Matters of judgement or discretion should be carefully considered to ensure that there is no inappropriate restrictive modelling in the automated rule base, and that discretionary decisions are capable of scrutiny and review.

- The underlying rules of automated systems should be readily understandable and publicly available.

- Automated systems should have the capability to automatically generate an audit trail of the decision-making path. This capability should also be able to generate statements of reasons or notification letters, and be available for external scrutiny.

‘... to assist public officials understand how key administrative law and public administration principles apply to automated systems ...’

Maintaining these principles benefits individuals who are affected by administrative decisions that may have been automated or assisted by automation. Adherence to these principles also enables external review agencies like the Ombudsman to investigate such administrative decisions more easily.

Cooperation with other oversight agencies

The Ombudsman’s office can be considered to be one part of the ‘integrity’ arm of government. It is one of a number of independent statutory agencies that discharge a ‘watchdog’ role in relation to the public sector. Some of those agencies have a role similar to the Ombudsman of receiving and investigating complaints from the public, initiating inquiries into systemic issues in government administration, or auditing compliance by agencies with legislative requirements. Examples are the Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS), the ANAO, the Privacy Commissioner, and the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI). Given our similar objectives of oversighting and improving government administration, we continue to look for ways to work cooperatively with these agencies, to complement each other’s work and to avoid unnecessary duplication of effort.

Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

ACLEI was established in December 2006 to detect, investigate and prevent corruption in the Australian Crime Commission, the Australian Federal Police and other prescribed Australian Government agencies with law enforcement functions. We meet as required to share information and discuss issues of mutual interest.

Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security

The Ombudsman and the IGIS continued to work together during the year, discussing common issues that arose in the handling of complaints about Australian Government agencies. For example, a number of complaints in the immigration area relate to delays in processing visa applications due to the time involved in undertaking external security checks. In some cases the check is conducted by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, over which the IGIS has jurisdiction. We liaised with the IGIS and refined our contact and referral procedures relating to the investigation of such cases.

Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission

During the year the Ombudsman and the President of the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission agreed upon a protocol for complaint handling between our agencies to reduce duplication of effort. We also agreed on a procedure to coordinate visits to immigration detention centres to maximise the opportunities for detainees to raise issues of concern, while reducing the impact on the day-to-day operations of the centres.

Privacy Commissioner

Privacy Commissioner

In November 2006 the Ombudsman and the Privacy Commissioner signed an agreement to enable greater cooperation when dealing with privacy-related complaints. The aim of the agreement is to facilitate exchange of information and avoid unnecessary duplication between the two offices. The agreement allows for the exchange of relevant information where both offices are considering the same issue; joint investigation; and the referral of complaints to the other office if it is relevant and the complainant consents.

Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force

The Ombudsman works closely with the Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force (IGADF) to ensure the most appropriate agency takes carriage of issues within their particular areas of responsibility. This approach has proven effective in dealing with persistent complainants, in finalising complaints that have become protracted, and in avoiding investigation of the same complaint issues by both organisations.

In the past year we have participated in joint training activities. Senior staff from our office regularly gave presentations at IGADF training courses. Similarly, at the invitation of the IGADF, we observed the practices employed during IGADF military justice audits, which are conducted at military units throughout Australia. This experience increased our understanding of military justice issues that the IGADF encounters and provided us with some ideas about how we could use similar techniques and methods in our own Defence investigations.

In April 2007 the IGADF also co-hosted a series of familiarisation visits for Ombudsman staff to Defence facilities around Australia. The visits helped our staff develop a better understanding of Defence issues, such as the pressure which can arise from an increased operational tempo, and the conditions in which many Defence personnel live and work.

Administrative Review Council

The Ombudsman is an ex officio member of the Australian Review Council, established by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal Act 1975 Part V. The Council provides advice to the government on administrative law issues and reform. During the year the Ombudsman was a member of the Council’s sub-committees responsible for reports on coercive information gathering powers, and complex business regulation, and for the development of a series of Best Practice Guides to Decision Making (to be launched in August 2007). The work of the Council is covered in a separate annual report prepared by the Council.

Meetings with other oversight bodies

We continued to work cooperatively with other oversight agencies by participating in multi-agency forums on issues of mutual interest.

In September 2006 we participated in a forum ‘Responding to the Anti-Terrorism Legislation’ jointly hosted by the Equal Opportunity Commission of Victoria, the Institute for International Law and the Humanities of the University of Melbourne, and the Federation of Community Legal Centres. Our staff gave a presentation on the role of the Ombudsman in relation to federal counter-terrorism law.

In February 2007 the Acting Ombudsman participated in a Police Accountability Round Table hosted by the Victorian Office of Police Integrity, to discuss police oversight and corruption prevention.

We also met during the year with the Inspector-General of Taxation, and provided information to his office to assist in its inquiries.

Own motion and major investigations

The Ombudsman can conduct an investigation as a result of a complaint to the office or on his own motion. During 2006–07 we publicly released 13 reports on own motion or major investigations.

Seven of the reports covered cases referred to the office by the Australian Government concerning the immigration detention of 247 people by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC). Other reports dealt with:

- the ATO’s administration of garnishee action

- Strand I funding decisions by the Australian Film Commission

- the Migration Agents Registration Authority’s complaint-handling process

- the management of complaints about unacceptable behaviour in the Australian Defence Force

- complaint-handling systems in airports

- a review of AFP ACT Policing’s Watchhouse operations.

Further details on most of these reports are provided in Chapter 5—Challenges in complaint handling and Chapter 7—Looking at the agencies, and all are available on our website at www.ombudsman.gov.au.

In 2007–08 we expect to finalise a number of other own motion investigations and commence some new ones, as detailed in Chapter 7.

International cooperation and regional support

Under our international program we continued to work with colleagues in other Ombudsman offices to improve public sector capacity in the Pacific, Papua New Guinea (PNG), Thailand and Indonesia. The program assisted Ombudsmen in the region to develop management strategies tailored to their specific challenges through placements, short advisory visits, and ongoing dialogue.

Over the last twelve months, our programs focused on activities to broaden the social impact of high quality complaint investigation services.

- In Indonesia we continued working to extend access to the National Ombudsman Commission (NOC) to more people in more areas.

- Our work with the PNG Ombudsman Commission helped to reinforce cooperative relationships with other law and justice agencies, contributed to better use of information technology and helped reduce complaint backlogs.

- In the Pacific we strengthened our existing network of Pacific Island Ombudsmen and began to expand opportunities for those Pacific countries currently without an ombudsman.

- We completed a successful three-year partnership with the office of the Thai Ombudsman. In this final year, we supported activities to strengthen community outreach, to improve use of information technology and to reduce complaint backlogs.

Our work in PNG, Samoa and Thailand has built institutional capacity on a number of levels, giving individuals an opportunity to extend their professional skills, while also supporting larger scale institutional and sectoral change.

PNG Ombudsman Commission police oversight project

The impact of the Twinning Program on the Ombudsman Commission of Papua New Guinea has been encouraging and very obvious. One area where the program has had a visible strategic impact is on the relationship between the Ombudsman Commission of Papua New Guinea and law enforcement agencies.

Mr John ToGuata, Director of Operations, Ombudsman Commission of PNG

A particular project of great importance in which the office has been involved is the PNG Ombudsman Commission Police Oversight Project. One step in this project was a placement in Canberra of Mr John Hevie, the PNG Ombudsman Commission manager responsible for overseeing the investigation of complaints about the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary. Mr Hevie observed our procedures for overseeing investigation reports of the AFP and the way our staff work collaboratively with the AFP in resolving complaints.

On his return to PNG, Mr Hevie was responsible for finalising the memorandum of agreement between the Ombudsman Commission and the Royal Papua New Guinea Constabulary. A senior investigator with our Law Enforcement Team worked with the Police Oversight Project during a placement to PNG to assess the resource implications and possible implementation issues of a range of oversight models.

On 1 June 2007 the Police Oversight Project entered a new stage in PNG with the signing of a memorandum of agreement between the Commissioner of Police and the Chief Ombudsman for an Ombudsman Oversight Mechanism for Complaints Against Police. The agreement aims to regain the public’s confidence in investigation of complaints against police personnel and represents a heightened commitment between the two agencies to work together in the best interests of the public.

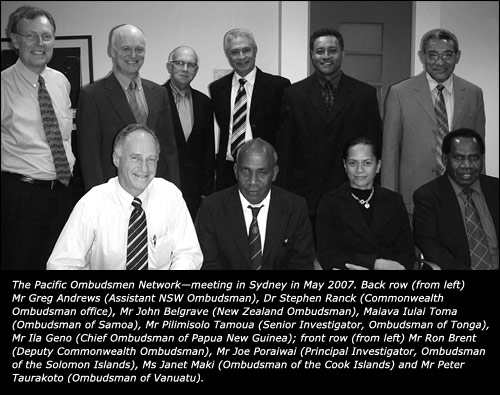

The Pacific Ombudsmen Network

During the year we participated in a forum with the Ombudsmen, or their representatives, from the Cook Islands, New South Wales, New Zealand, PNG, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga and Vanuatu. The forum focused on building the framework for more regional cooperation in the Pacific Island Forum states.

Mr Maiava Inlai Toma, Ombudsman of Samoa has stated:

’Samoa has been directly assisted by the office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman under the umbrella of the ‘Pacific Ombudsmen Network’ since the earliest days of the Network’s establishment. Activities have focused on strengthening identified needs of the Ombudsman’s office. I have absolutely no complaints about the quality, either of the specific assistance given or of the people that were involved in its delivery. I would like to emphasise however that the benefit to us of involvement in the Network has been much more than functional improvements that may have been designed into the actual activities. The physical existence and operation of an Ombudsman office in a country that is not a mature democracy does not necessarily mean very much. In my own country, the priority task all along has been to achieve understanding, acceptance and respect for the Ombudsman function by the Government and by the people to be served by the Ombudsman. In this endeavour the existence of the Network and membership in it has been invaluable.

’It has to be borne in mind that conventional ombudsmanship is not something that one makes up as one goes along or brings about by a wave of a magic wand. Acceptance and respect for it has to be freely given for it to realise its potential as a powerful yet friendly tool for fairness and good governance that is indispensable in today’s democratic society. Pacific countries are striving for this ideal and they are spurred on by the achievements and successes in neighbouring countries where the ombudsman function is strong and well established. Involvement at the personal level with fellow ombudsmen from those jurisdictions and the latter’s own demonstrated interest in the strivings of the struggling Pacific Islands ombudsmen generate immense encouragement and reassurance. It is vital in my view that the Network be maintained as we know it today and that it be at the centre of regional efforts and developments in our area of interest.’

Case Handling at the Office of the Thai Ombudsman

The Thai Ombudsman office has learned a great deal from the thirty-year experience of the Commonwealth Ombudsman ... Thai Ombudsman staff who received training came back with a fuller understanding of the Ombudsman’s task and operational systems. More than 70% of the officers who participated in the partnership program with the Commonwealth Ombudsman have subsequently been promoted to senior investigator and senior officer positions, and continue to support organisational development in their new roles. We hope that the relationship between the two offices will continue well into the future.

Ms Roypim Therawong, Deputy Section Head, Technical Support Division, Office of the Thai Ombudsman

During the year we hosted staff from the Thai Ombudsman office. They participated in ‘train the trainer’ seminars, covering issues such as dealing with difficult complainants, investigation planning, mediation and negotiation. On their return to Thailand a fortnightly training program was implemented for all Thai Ombudsman staff. The training manual was translated and published in the Thai Ombudsman Journal. More than 1,500 copies were distributed to schools, universities, institutes, government and non-government organisations, spreading the benefit of this program beyond the office to the general public.