Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2008-09 | Chapter 6 Looking at the agencies

Chapter 6 | Looking at the agencies

Introduction

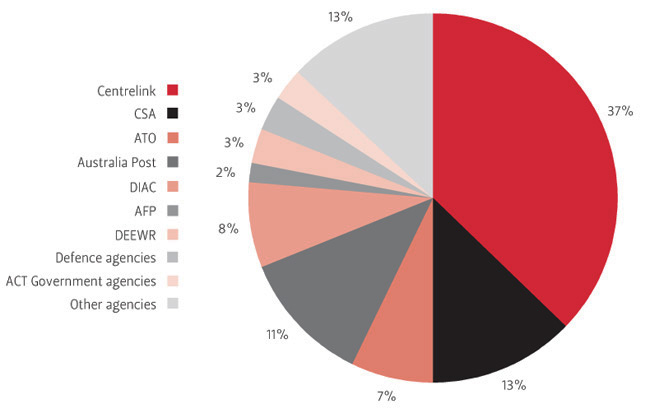

Most of the approaches and complaints received about Australian Government agencies that are within the Ombudsman's jurisdiction (79%) relate to the following agencies:

- Centrelink—7,226 approaches and complaints

- Child Support Agency—2,471 approaches and complaints

- Australia Post—2,219 approaches and complaints

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship—1,459 approaches and complaints

- Australian Taxation Office—1,422 approaches and complaints

- Department of Education, Employment Workplace Relations—571 approaches and complaints.

This chapter assesses our work with these agencies in handling complaints and dealing with other broader issues during 2008–09. It also looks at other areas of our work:

- as Defence Force Ombudsman, dealing with complaints by current and former members of the Australian Defence Force

- dealing with complaints about the Australian Federal Police, including under the role of Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- the broader Postal Industry Ombudsman role

- dealing with Indigenous issues, and in particular approaches and complaints raised in the context of the Northern Territory Emergency Response

- dealing with complaints about some other Australian Government agencies

- handling complaints about the way agencies deal with freedom of information requests.

The last part of the chapter covers the monitoring and inspections work we undertake for Output 2—Review of statutory compliance in specified areas.

Figure 6.1 shows the number of approaches and complaints received in 2008–09 about agencies within the Ombudsman's jurisdiction. Detailed information by portfolio and agency is provided in Appendix 3—Statistics.

FIGURE 6.1Approaches and complaints received about within jurisdiction agencies, 2008–09

Australian Taxation Office

Complaints overview | Most frequent complaints | Reviewing tax administration

Introduction

The Ombudsman has been investigating complaints about the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) since 1977, when the Ombudsman's office commenced operation. The Ombudsman was given the title of Taxation Ombudsman in 1995 to give a special focus to the office's handling of complaints about the ATO. This was a result of recommendations of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts, which recognised the unequal position of taxpayers and the ATO.

As the only external complaint–handling agency to which taxpayers can bring complaints about the ATO, the Taxation Ombudsman is uniquely placed to draw on our regular contact with taxpayers to assist in improving taxation administration.

Complaints overview

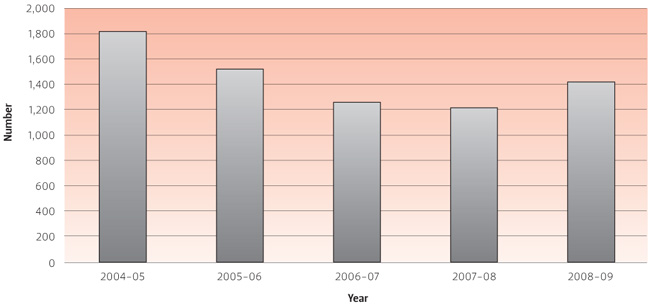

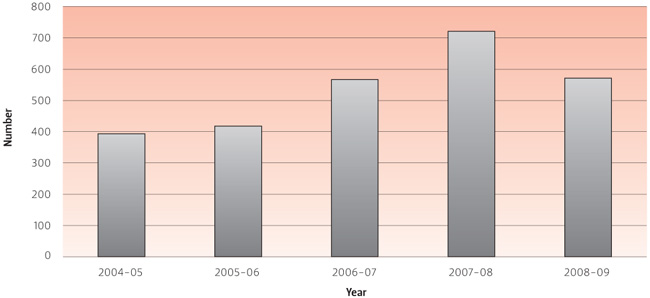

In 2008–09 we received 1,422 approaches and complaints about the ATO, an increase of 17% from the 1,219 received in 2007–08. While this is the highest number of complaints about the ATO in three years, it is in line with the average number of complaints over the past five years, as Figure 6.2 shows.

The ATO itself also received an increased number of complaints in 2008–09. These increases probably stem from the impact of some significant events during the year, including the tax bonus payment and changes to some ATO systems as part of its Change Program. We will closely monitor Change Program releases during 2009–10 for possible problems.

During the year we finalised 1,400 approaches and complaints, of which 321 (23%) were investigated. While this is more than double the percentage of cases investigated last year, this increase is largely due to a change in categorisation of tax complaint investigations. Most of the complaints we investigate have already been through the ATO's complaint–handling system. As a first stage of investigation we seek information about the outcome of the ATO complaint handling. Previously we did not record this stage as an investigation, but from this year on it will be included as an investigation in our reports.

We achieved one or more remedies in 49% of the cases we investigated. The most common remedies were better explanations (28% of all remedies), apologies (21%), financial remedies (9%) and actions being expedited (7%).

We transferred approximately 14% of the complaints directly to ATO Complaints under the assisted transfer process introduced in 2007. This is a significant decrease from the 25% complaint transfer rate in 2007–08. We have not analysed fully why there has been a drop in the rate of transfers. We consider that the assisted transfer process is a valuable service to assist people to pursue their complaints through the most appropriate mechanism.

FIGURE 6.2Australian Taxation Office approach and complaint trends, 2004–05 to 2008–09

Most frequent complaints

The complaints we received covered a broad range of ATO activities and products. The most frequent complaints related to the lodgement and processing of forms (31%), debt collection (15%), superannuation (11%), ATO complaint handling (8%) and taxpayer information (6%). While these have been the most frequent complaint topics in previous years, the most significant change is an increase in the number and proportion of lodgement and processing complaints.

Lodgement and processing

Almost a third of the complaints we received during the year were about lodgement and processing issues, most commonly related to income tax assessments and refunds. Many of the complaints were related to delays in receiving a refund or confusion about the basis for assessment. There was also an increase in lodgement and processing activity in the ATO, following the announcement of the Australian Government's tax bonus payment, which included as an eligibility requirement that a taxpayer had lodged their 2007–08 income tax assessment.

The case study Processing error resolved is an example of how we were able to assist a complainant to resolve an ATO processing error that resulted in a debt wrongly being raised against him.

Processing error resolved

Mr A complained to us about an outstanding pay as you go (PAYG) instalment debt. Mr A had been contacted by one of the ATO's outsourced debt collection agencies about payment of the debt. According to Mr A he did not have a PAYG instalment debt because his primary income since 2000 had been Centrelink benefits.

As a result of our investigation, the ATO identified that it had failed to properly remove Mr A from the PAYG instalment system after he had advised it that he would not be lodging income tax returns because he did not receive sufficient income. Mr A was actually entitled to a refund of more than $3,000.

The ATO apologised to Mr A and paid the refund to his bank account.

Debt collection

Complaints about debt collection increased from 12% of complaints in 2007–08 to 15% in 2008–09. This followed an earlier increase in 2006–07. The most frequent issues were payment arrangements, debt waiver or write off, actions of debt collection agencies and garnishee and bankruptcy action. In most cases the appropriate outcome from these complaints was to provide the taxpayer with a better explanation about the debt situation and their options for resolving it.

In some cases, such as Unfair garnishee decision, we highlighted problems with ATO administration of debt collection, leading to fairer decision making.

Unfair garnishee decision

Ms B complained that it was unfair of the ATO to garnishee her entire bank account balance for a partnership debt of $60,000. She had only found out about the debt two weeks earlier as previous correspondence had been sent to her former business partner. Ms B had advised the ATO that she could not afford to pay. She agreed to contact the ATO after seeking professional advice about her options, but did not do so by the agreed date. Without attempting to contact Ms B again, the ATO issued a garnishee notice for 30% of the debt, resulting in the total balance of her bank account being sent to the ATO. While the garnishee notice was not legally incorrect, we expressed concern to the ATO that it had not acted consistently with its policy to take into account the likely implications of garnishee action on a debtor's ability to provide for a family or maintain the viability of a business.

The ATO agreed that it should have made further enquiries about the balance of Ms B's account to enable it to make an informed decision about the appropriate action to take. The ATO also advised that it would explore a possible modification to its garnishee practices, to ensure that only a specified and reasonable percentage of the contents of a bank account would be removed under a garnishee.

As part of our process to follow up on recommendations arising from complaints, we will check with the ATO about the implementation of any changes to their garnishee practices and procedures.

Superannuation

In 2008–09 close to 12% of the complaints we investigated were about superannuation. The number of such complaints has decreased over the past three years.

One area of increase was in complaints related to superannuation co–contribution. This increase was related to problems with the ATO's implementation of one of its Change Program releases in February–March 2009 that affected superannuation co–contribution payments. The ATO advised that payments to around 200,000 people were delayed as a result. In June 2009 the ATO implemented a 'workaround' that allowed it to expedite payments to people eligible to receive these payments who experienced hardship as a result of the delay (usually people who are relying on their superannuation in retirement or because of adverse personal circumstances). The ATO advised that it is working with superannuation funds to clear the backlog of payments and interest will be paid for the period of delay. We expect to continue receiving complaints about this issue until the ATO fixes the problem completely.

There was a decrease in complaints from employees about unpaid superannuation (32% of superannuation complaints compared to 47% in 2007–08: a decrease from 52 to 32 complaints). We attribute this decrease to two factors. One is the improved processes the ATO put in place to better manage investigations and recover established superannuation debts, as a result of additional funding provided in the 2007–08 Budget. The other factor is that, following legislative changes to secrecy restrictions, the ATO can now provide more information to employees about progress in investigating unpaid superannuation guarantee. Even though the number of these complaints has decreased, we consider that there is value in further scrutiny of this area of ATO administration and we will cooperate with the Inspector–General of Taxation's review of the administration of the superannuation guarantee charge in 2009–10, discussed later.

The case study Compassionate response is an example of how the ATO responded effectively and compassionately to our approach on behalf of a complainant who was seeking the release of superannuation funds held by the ATO.

Compassionate response

Ms C had been diagnosed with terminal cancer with less than six months to live. She had superannuation funds in the Superannuation Holding Accounts special account (administered by the ATO) and she wanted this money paid directly to her so that she could take a holiday with her son before she became too ill to do so. Ms C complained to us that the ATO had advised that it could take three months for her to be able to access her funds. While the ATO normally undertakes to process payments within 21 days of receiving the necessary information, a scheduled upgrade to the superannuation system would interrupt these types of payments for the next few months.

When Ms C complained to us, we asked the ATO to look at the matter urgently. The ATO responded within three days and advised that, because of Ms C's exceptional circumstances, she should complete a withdrawal form and send it to ATO Complaints so that they could issue a manual cheque. This would take two weeks but it was still much sooner than would have occurred if the funds were transferred to her superannuation fund. The ATO Complaints manager took charge of the process to ensure that Ms C received the funds as quickly as possible.

Taxpayer information

Taxpayers rely on the ATO to accurately record and manage their personal information. If a mistake is made, it is important that the ATO acts appropriately to address this, taking into account how the mistake occurred. The case study Incorrect assumption resolved shows how we were able to assist a complainant to have a mistake in processing their personal information corrected.

In 2008–09 we received a number of complaints related to taxpayer information security and compromise. They highlighted two areas of concern. The first is the ATO's approach to resolving a suspected duplication (either two taxpayers using the same tax file number (TFN) or two TFNs thought to relate to the same taxpayer). The case study Error in resolving suspected TFN duplication is an example of this type of complaint. The second area of concern is the effectiveness of the ATO's systems and processes for deterring TFN fraud and assisting taxpayers whose identities have been stolen or misused. Cases involving TFN compromise and suspected fraud are complex and involve judgement and sensitivity to resolve.

Incorrect assumption resolved

Ms D was a serving Army officer. Her tax agent recorded her title as Captain D when lodging her tax returns. Based on this information, ATO staff made the assumption that Ms D was in fact a male and updated its records to reflect this, without contacting her for clarification.

Ms D made repeated requests to the ATO to correct her record, but it did not do so. At one stage ATO staff asked Ms D if she had had a sex change operation, and subsequently told her that she would have to provide her birth certificate to prove she was female.

As a result of our investigation, the ATO updated its databases without requiring further evidence from Ms D and sent a letter of apology to her.

Error in resolving suspected TFN duplication

Mr E complained that he had not received tax refunds for the past two years and he could not submit a tax return because he did not have a valid TFN.

When Mr E lodged his income tax return, he discovered that the ATO had processed another person's tax records with his TFN. The ATO had incorrectly decided that he and another taxpayer with similar identifying information were the same person, and merged information together under Mr E's TFN. Mr E's tax return was processed as an amendment, adding the income from the two lodgements together. Our investigation highlighted a lack of action to correct the error or to consider how it could have happened and whether there were appropriate safeguards against it recurring.

As a result of our investigation, the ATO apologised to Mr E, and expedited action to provide a new TFN and his tax refunds. The ATO also reviewed its TFN compromised procedures to ensure that investigating officers are prompted to make adequate enquiries to properly identify if there are two taxpayers with similar details.

Reviewing tax administration

In addition to resolving individual complaints, we use information from complaints to identify potential systemic problems in tax administration. Through our external project work, including own motion investigations and less formal reviews, we review the effectiveness of specific areas of tax administration and consider areas for improvement.

During the year we worked on three own motion investigations:

- the ATO's processes and practices for re–raising debt

- the operation by several agencies of the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme (more detail is provided in the Centrelink section of this chapter)

- the ATO's use of its unannounced access powers.

We also finalised an informal review of aspects of the superannuation guarantee.

We discontinued an own motion investigation into the complaint–handling practices of state tax agents' boards. We decided that this would no longer be pertinent because these boards will be replaced by a national Tax Practitioners Board under new legislation reforming the regulation of tax agent services.

In January 2009 we made a submission to the inquiry by the Senate Standing Committee on Economics into the Tax Agent Services Bill 2008. Our submission was based on observations from the complaints we receive about tax agents and the various state–based tax agents' boards.

If implemented effectively, the reforms are likely to provide a more centralised and structured approach to the regulation of tax practitioners, and should facilitate increased professional accountability and service delivery standards to the benefit of taxpayers, tax professionals and tax administration generally. We look forward to working with the new national Tax Practitioners Board.

Re–raising written–off tax debts

This investigation was initiated in response to complaints we received about the operation of ATO policies to re–raise debts which had been written off many years earlier, sometimes where taxpayers were unaware that they still had a collectable debt. The trigger for a debt being re–raised was a taxpayer receiving an income tax assessment of over $500 credit. In some cases taxpayers were asked to pay the general interest charge (GIC) applied back to the write–off date. In other cases the GIC was remitted automatically.

The investigation report Australian Taxation Office: Re–raising written–off tax debts (Report No. 4/2009), published in March 2009, identified a number of areas where the ATO could improve its administration of debt re–raise decisions, including:

- improving communication with taxpayers

- more comprehensive recording of reasons for decisions

- ensuring that the criteria used for deciding to re–raise debts are clearly related to whether it is economic to pursue the debt and efficient, effective and ethical to do so

- monitoring the impact of the ATO's bulk write–off process to ensure it is operating appropriately.

The ATO agreed or partially agreed to all the recommendations in the report. It implemented revised criteria for re–raising debts, with a view to promoting a more consistent approach to the re–raise of debt and avoiding the impact on low income earners that resulted from the previous approach.

Unannounced access powers of the ATO

Many government agencies administer legislation that authorises staff to access premises or information—often described as coercive powers. The ATO administers several pieces of legislation that contain such provisions. One of the best known and most commonly used is s 263 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 that empowers the Tax Commissioner or his delegate to enter premises, private or business, for the purpose of administering the tax legislation.

The ATO regularly uses these powers to gain access to premises to examine and copy documents. The ATO has in place internal checks and balances, but the use of these powers receives only intermittent scrutiny by external government bodies.

During 2008–09 we commenced an investigation into the ATO's unannounced access powers. The aim of the investigation is to foster good public administration by providing independent oversight of the use of coercive powers and to identify areas for improvement. The report from this investigation will be published in 2009–10.

Informal review of superannuation guarantee charge

During the year we finalised an informal review of ATO administration of the superannuation guarantee charge (SGC). We revised the scope of this review after the ATO implemented changes to SGC administration and received additional funding to address a backlog in unpaid superannuation cases. Our revised review looked at the two main employee complaint issues we had received about the SGC:

- ATO delay in collecting unpaid superannuation from employers

- lack of information provided by the ATO to employees about the collection of their unpaid superannuation.

The Commissioner of Taxation agreed in principle with our recommendations that the ATO:

- continue reviewing the processes and resources used to increase the timeliness of follow–up and finalisation of investigation of employee notifications about employers' failure to pay their superannuation entitlements and collection of established superannuation debts

- review its business processes to ensure that employees receive advice when no further action is being taken by the ATO to collect unpaid superannuation (pending full implementation of the Change Program)

- ensure its new systems are able to provide management and client information for the entire process from investigation of unpaid superannuation claims to payment of money collected from employers, and in particular the collection of unpaid superannuation guarantee.

We are continuing to monitor the ATO's administration of SGC and we receive updates about progress with business and systems improvements. In the coming year, we will work closely with the Inspector–General of Taxation in his review of the ATO's administration of SGC.

The review will consider the ATO's:

- risk assessment strategies for the SGC and ATO implementation of strategies to improve compliance by employers (such as education, employer assistance, audit and enforcement)

- communication strategies the ATO could adopt with employees who have raised concerns about their employer's compliance, the timeliness of actioning employee notifications and the level of information provided by the ATO to employees about the collection of unpaid superannuation guarantee

- timeliness in collecting unpaid superannuation guarantee from employers.

Centrelink

Complaint themes | Centrelink payments and benefits | Service delivery issues | Cross–agency issues | Compensation for Detriment Caused by Defective Administration | Looking ahead

introduction

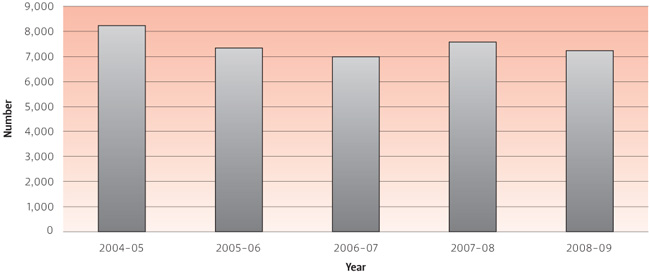

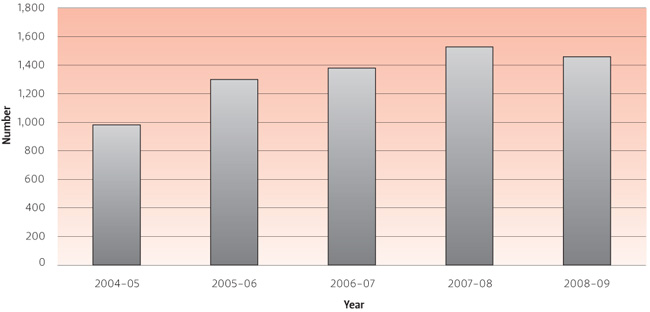

In 2008–09 the Ombudsman's office received 7,226 approaches and complaints about Centrelink, compared to 7,573 in 2007–08, a 5% decrease. Given the volume, complexity and diversity of Centrelink's work, it is not surprising that we receive this number of approaches and complaints. Figure 6.3 shows the trend in approaches and complaints from 2004–05 to 2008–09.

Complaint themes

The largest number of complaints about Centrelink was from people claiming newstart allowance (NSA), followed in order by disability support pension (DSP), family tax benefit (FTB) and age pension. Common issues raised by complainants were Centrelink review of decisions, delays, the management of debt raising and recovery, and payment pending review.

From the beginning of 2009 there was a notable increase in complaints about access to Centrelink services. The large majority of these were calls made to our office by people unable to get through to Centrelink's normal service or customer relations unit phone lines. Through liaison with Centrelink we were able to identify this trend early on, and inform our public contact officers that Centrelink's capacity was being affected by the series of natural disasters, including the Victorian bushfires, and the economic stimulus packages. While this did not resolve the issue for those complainants, these timely explanations were valuable in helping to manage their expectations and the demand on our resources for complaint investigation.

FIGURE 6.3Centrelink approach and complaint trends, 2004–05 to 2008–09

We have found that Centrelink is generally very responsive to our enquiries and suggestions. Complaints can be resolved within as little as 24 hours of being received, as the case study Urgent response shows.

Urgent response

Ms F complained about Centrelink's delay in processing her claim for carer payment in respect of her critically ill son. She contacted Centrelink for an update nine days after lodging the claim. Centrelink advised her that it was experiencing a systems problem that prevented her claim from being progressed. Ms F contacted Centrelink a number of times over the next few days, attempting to have the matter resolved, with no success. When she was told the matter could take up to 49 days to correct, Ms F complained to us.

We contacted Centrelink the next day to establish what was delaying the processing of Ms F's claim. Centrelink indicated that a systems error had been identified in her claim and the matter had been referred to Centrelink's systems section to resolve. We asked Centrelink to give the matter some priority, given the sensitivity of the case. As a result, Centrelink resolved the matter and granted carer payment to Ms F that day.

Often when we investigate an individual complaint, it becomes apparent that the issue being complained about is more widespread or systemic. In these situations we usually ask Centrelink to take a course of action that will ameliorate the problem so that it does not recur. The case study Misleading information illustrates how consideration of an individual complaint can provide a systemic solution.

Misleading information

Ms G complained that Centrelink's Disability and Carer Payment Rates brochure stated that the basic conditions for eligibility for DSP include an 'inability to work for at least the next two years as a result of impairment'. Ms G argued that potential claimants who might be eligible for DSP would not apply on the basis of the apparently definitive information in the brochure. More detailed information in other publications explained that the relevant level of incapacity was inability to work for 15 hours or more per week. After we raised the matter, Centrelink undertook to update the brochure from 1 July 2009 to include a reference to the 15–hour rule.

Centrelink payments and benefits

Job Capacity Assessments

Job capacity assessments (JCAs) assist Centrelink to determine eligibility for DSP and activity test requirements for activity–tested customers. The JCA program was administered by the Department of Human Services (DHS) in 2008–09, but is now administered by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). Centrelink carries out approximately 50% of the assessments.

We received a number of complaints about the JCA process that indicated a lack of confidence in the assessor's understanding of the complainant's condition. Although we investigated few of these cases, it was clear that the perception that assessors did not have an adequate appreciation of the complainant's medical condition was widely held.

In early 2008 the Ombudsman's office published an own motion investigation report Implementation of job capacity assessments for the purposes of Welfare to Work initiatives: Examination of administration of current work capacity assessment mechanisms (Report No. 5/2008). One of the major recommendations arising from this report was that assessors be encouraged to consult treating doctors where it appears a lack of information about a person's medical condition may affect the assessor's understanding of its impact. The agencies commented that often doctors are unwilling to take the time to discuss their patients' medical issues over the phone, given they have already completed a medical report form, especially when there is no financial incentive to do so.

The 2009–10 Budget measures included funding for a Health Professional Advisory Unit within Centrelink to give assessors and Centrelink staff making decisions about income support eligibility specialist medical advice to complement a claimant's treating doctor's report. In addition, payments for doctors will be available when they provide additional diagnostic or further information about a claimant at the request of the unit.

We believe that these measures will go a long way in addressing the recommendation. The changes are due to take effect from 1 July 2010.

Acute and terminal illness

The Ombudsman's 2007–08 annual report highlighted the experience of some people suffering from acute or terminal illness, their inability to access DSP, and the difficulties in having to rely on the activity–tested alternatives such as NSA or parenting payment. In March 2009 the Ombudsman released a report Assessment of claims for disability support pension from people with acute or terminal illness: An examination of social security law and practice (Report No. 2/2009). The case study Limited information, taken from that report, illustrates the problems that people can experience.

Limited information

As part of her treatment for leukaemia Ms H commenced aggressive chemotherapy and radiation therapy almost immediately. The DSP medical report completed by her treating doctor indicated that she did not have a terminal condition with a prognosis of less than 24 months and that her condition was likely to improve significantly within the next two years. The doctor did not indicate that he would like to discuss any aspect of his report with Centrelink.

An assessor conducted a JCA on Ms H on the basis of the information provided in the DSP medical report. Although the doctor's diagnosis indicated Ms H had a particularly aggressive and usually terminal form of leukaemia, the JCA assessor did not have the necessary information to identify that Ms H's condition was serious and likely to prevent her from working for more than 24 months.

Centrelink rejected Ms H's DSP claim because it was not satisfied her condition was permanent for the purposes of the social security law. Instead she was granted NSA with an exemption from the activity test on the basis of medical certificates from her treating doctor. Ms H was still required to submit a continuation for payment form to Centrelink every 10 weeks.

The Ombudsman's office noted that in light of her ongoing and exhausting treatment it was physically difficult for Ms H to obtain and submit new medical certificates quarterly and a continuation for payment form every 10 weeks.

As a result of our intervention, Ms H's doctor provided further information that revealed that his initial prognosis and Ms H's own assessment of her circumstances had been overly optimistic. It had become clear that there would be no significant improvement in her condition for at least two years. Based on this information Centrelink decided to review its original decision and grant Ms H DSP from the original date of claim.

The Ombudsman report made seven recommendations for consideration by the four agencies involved—Centrelink, DEEWR, DHS and the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA).

The report recommended the creation of a new category of payment for people experiencing an illness requiring a lengthy period of treatment or recovery, or requiring further investigation to reach a more conclusive prognosis. It also recommended that a list of conditions might be developed that would automatically qualify a customer. In the alternative, the report suggested that consideration be given to allowing longer periods of exemption from activity testing for people who were on NSA or youth allowance.

While not agreeing with the recommendations, DEEWR and FaHCSIA acknowledged the issues and undertook to review them in order to achieve a more sensitive response. Changes made as part of the 2009–10 Budget should go some way to addressing the concerns raised in the report. The Minister for Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs announced a simplification of the DSP assessment to fast–track claimants 'who are clearly or manifestly eligible due to a catastrophic, congenital disability or cancer, enabling them to receive financial support more quickly'. A new policy will be implemented from March 2010 to allow customers with a serious illness receiving an activity–tested payment to be granted a long–term exemption from the activity test with a significant reduction in reporting requirements and without the need for referral to a JCA or to repeatedly lodge medical certificates.

The report recommended changes to the advice given to doctors and the format of the report they complete, in order to give them further context on how their responses will be treated in the decision–making process. It also recommended that JCA assessors reviewing the medical report be encouraged to seek further information from doctors. All the agencies agreed on the need to support doctors and facilitate their involvement in the process.

Economic Security Strategy payment

On 14 October 2008 the Government announced the Economic Security Strategy payment (ESSP) that was payable to eligible pensioners, veterans, families and concession card holders. FaHCSIA was responsible for the policy of the payment while Centrelink was responsible for its delivery.

The majority of payments were to be delivered between 8 and 19 December 2008. In order to qualify for the payment, a person had to be in receipt of an eligible pension or family assistance payment, or be the holder of an eligible concession card, on 14 October 2008.

Shortly after the majority of ESSPs had been made in December 2008, we received a large number of complaints from people who were expecting the payment, but had subsequently been advised by Centrelink that they did not qualify. These people told us that they did not qualify because they did not receive an instalment of their eligible payment for a period covering 14 October 2008. Further investigation revealed that people must have received an instalment of their payment for the period including 14 October 2008 in order to qualify for the ESSP. A large number of the complaints we received were from people who qualified for an eligible payment, but their rate had been set to nil for the fortnight that included 14 October 2008 due to casual earnings.

While this criterion was clear in the legislation governing the ESSP, it was not as clear in the communication regarding the payment, including media releases, advertisements, and fact sheets on the agencies' websites.

At the end of the reporting period we were still in discussion with Centrelink and FaHCSIA about a number of issues stemming from the administration of the ESSP. A draft Ombudsman report had been prepared and provided to the agencies.

Equine influenza assistance

Our 2007–08 annual report discussed some of the issues we observed through complaints about the Equine Influenza Business Assistance Grant (EIBAG) which assisted those affected by the equine influenza outbreak and related movement restrictions. The Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (DAFF) held policy responsibility for the EIBAG and Centrelink administered it.

In May 2008 we received five complaints about Centrelink's decision to reject claims for the third round of assistance. The policy guidelines for the third EIBAG specified that, in order to qualify, businesses needed to be located in, or demonstrate that the majority of their income was derived from, a restricted movement zone.

Each of the claims was rejected on the basis that the claimants were not located in a restricted movement zone, nor did they conduct their business activities in one. While this was true, each of the businesses relied on customers that were located in restricted movement zones and therefore derived their income from those zones. DAFF subsequently reviewed and upheld Centrelink's decisions on the basis that the claimants had not provided sufficient evidence to demonstrate that their businesses qualified for the payment.

Upon investigation it appeared that Centrelink had misinterpreted the EIBAG policy guidelines and had been rejecting claimants incorrectly on the basis of whether they were actually conducting business activities in a restricted movement zone, rather than whether their income was derived from a restricted movement zone. Further enquiries revealed that DAFF was aware that Centrelink had misinterpreted the guidelines, yet failed to intervene.

DAFF was, in fact, rejecting these claims on appeal on a different basis: that claimants failed to demonstrate they derived their income from a restricted movement zone. While this was the correct basis, many claimants would have been able to provide further evidence to demonstrate they derived their income from a restricted movement zone, had they been given the opportunity to do so. Given that applicants were not provided with the correct reason for rejecting their EIBAG claims by Centrelink originally, they were denied the opportunity to provide the necessary evidence when appealing to DAFF. DAFF did not acknowledge this. As DAFF would only review a case once, people who would have technically been eligible for the EIBAG missed out.

In November 2008 the Ombudsman published a report Centrelink and Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry: Claim and review processes in administering the Equine Influenza Business Assistance Grant (third payment) (Report No. 13/2008). As a result of this report, Centrelink (in consultation with DAFF) undertook to contact all claimants of the third EIBAG who had been rejected incorrectly and invite them to reapply with evidence that demonstrated they derived income from a restricted movement zone. As a result, an additional $2,315,000 was paid to 463 claimants whose claims were originally unsuccessful.

This demonstrates how a small number of complaints to the Ombudsman's office can result in far–reaching, substantial remedies for others who may not have contacted us.

Service delivery issues

Alternative servicing arrangements

For several years the Ombudsman's annual reports have referred to the number of complaints received about the withdrawal of face–to–face service options for customers whose behaviour has been inappropriate. The Ombudsman released an own motion investigation report Centrelink: Arrangements for the withdrawal of face–to–face contact with customers (Report No. 9/2008) in August 2008.

The report made five recommendations about the implementation of guidelines for alternative servicing which had been in place and supported by a Centrelink Chief Executive Instruction since February 2007. Despite staff training and the issuing of the instruction to support their introduction, the report found that inconsistent application of the guidelines continued. The main areas of concern were the provision of alternative contact details, the duration and review of arrangements, and the consideration of alternative approaches before face–to–face services were withdrawn. The report recommendations included that letter templates include advice about review rights, and that Centrelink record and monitor the implementation and regular review of arrangements. Centrelink agreed to all the recommendations.

We are aware that Centrelink has been reviewing its policy on alternative servicing arrangements since the publication of the report, and that updated guidelines currently under development are intended to address the concerns raised in the report. We have provided comments to Centrelink on these guidelines. The Ombudsman believes there needs to be greater clarity for both customers and Centrelink officers about how informal alternative service arrangements should be managed, and the continuing right of access to all face–to–face service points under those arrangements made clear to customers. The case study Banned for life illustrates this issue.

Banned for life

In 2005 Centrelink withdrew face–to–face servicing from Ms J for 12 months, a ban which was later extended to life. Following our intervention in September 2008, Centrelink restored face–to–face services because it had failed to review Ms J's case along with all other alternative servicing arrangements in February 2007 (as required by the Chief Executive Instruction).

In March 2009 Ms J was incorrectly told to leave a Customer Service Centre (CSC) because she was banned. Centrelink apologised to her, and gave her written advice of the arrangements in place. She was able to call the manager of her local CSC directly, or if she needed to visit an agent's office, she should call the CSC manager who would then arrange for her to have an appointment with the agency manager or a 'suitable staff member'.

In response to our enquiry about the failure to provide Ms J with details for a backup contact; start, end or review dates for the arrangement; or advice that she could ask for the arrangement to be reviewed, Centrelink advised that it had 'not entered into an alternative servicing arrangement with Ms J rather we have negotiated how to best meet her servicing needs in a different management response which is likely to have a more positive result'. Based on this conclusion, Centrelink did not believe it needed to apply the alternative servicing guidelines. Our view is that any decision to limit a customer's contact with Centrelink should be made according to the guidelines on the alternative servicing arrangements.

Reviews and delays

Our 2007–08 annual report noted continuing concerns with Centrelink's internal review processes. Concerns were expressed about:

- the practice of sending customer reviews to the original decision maker (ODM) when a customer has indicated that they want it referred directly to an authorised review officer (ARO)

- reviews not automatically progressing to an ARO review when the ODM has affirmed their original decision

- review forms which advise customers that, even if they ask to go directly to ARO review, the ODM may examine their matter first.

As the case studies No DSP and No card show, these problems continue. We have commenced an own motion investigation into Centrelink's internal review processes. We expect to release a report on the outcome of that investigation during 2009–10.

No DSP

Centrelink rejected Mr K's application for DSP in June 2008. Five days later, he asked for a review of the decision. More than four months after the initial review request, the ODM wrote to Mr K affirming the original decision and advising him that, as previously requested, a review by an ARO was underway. In November 2008 the ARO upheld the ODM's decision, and notified Mr K in writing nearly three weeks later. By that time Mr K had already lodged an appeal with the Social Security Appeals Tribunal, presumably on the basis of verbal advice of the review outcome.

No card

Mr L complained that he had sought a review of a decision not to grant him a Commonwealth Seniors Health Care Card at the end of December 2008. Centrelink advised us that, due to a large backlog of review requests, and given that the matter did not appear to involve an issue of hardship, it would not be given priority. By late April 2009, the matter had still not been seen by an ARO. In response to our investigation Centrelink apologised for the delay, and noted that it was improving its process for transferring cases between sites and staff, and increasing the number of staff to prevent this situation recurring.

Use of interpreters

In 2009 the Ombudsman's office conducted a cross–agency review of the use of interpreters, with the intention of providing best practice principles against which all agencies could measure their performance and make informed decisions about their potential for improvement.

The Ombudsman's report Use of interpreters: the Australian Federal Police; Centrelink; the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations; the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (Report No. 3/2009) identified eight principles for clear and comprehensive policies to guide staff in the use of interpreters. It also considered the provision of staff training, a community language scheme for multilingual staff, recordkeeping, complaint–handling mechanisms and the way in which agencies address challenges when using interpreters. Encouragingly, Centrelink's policies were found to generally align with best practice principles in the use of interpreters.

Inability to contact by phone

It is not uncommon for the Ombudsman's office to receive a few complaints from people who are experiencing difficulty getting through to Centrelink call centres when contacting the agency by telephone. However, during 2008–09 we received a substantially higher number of complaints about this issue.

We found that Centrelink had been dealing with abnormally large call volumes over 2008–09. Centrelink attributed this to the number of unusual functions it had to perform during the year. These included the delivery and operation of:

- the Economic Security Strategy payment

- the Household Stimulus payment

- assistance relating to the Victorian bushfires

- assistance relating to the Queensland floods

- the information line for the Mumbai crisis

- the swine flu hotline.

It appeared to us that Centrelink was handling the call volumes as best it could, given the circumstances. Centrelink advised us that customers would not be disadvantaged as a result of not being able to get through on the phone. For example, if a person was unable to report their income to Centrelink due to telephone congestion, Centrelink would take this into account in making decisions about the person's payment.

While we did not investigate the individual complaints, we were able to explain the reasons for the telephone difficulties to complainants and that they could contact us again if their payments were affected in some manner as a result of not being able to get through to Centrelink.

Cross–agency issues

Cross–agency issues frequently arise where one agency has policy responsibility for a scheme or payment, and another agency is responsible for delivery. One of the most common interdependencies involves the relationship between DEEWR and its contracted providers (providers of government employment services—now called Employment Service Providers) and Centrelink.

Income support recipients on activity–tested payments are usually required to register with a provider, and Centrelink supports provider referrals. Because of the relationship between a person's payment and the activities they are required to participate in with their provider, much information is exchanged between Centrelink, DEEWR and its providers. Sometimes this exchange is automatic, and invisible to the parties involved. At other times, the exchange relies on a manual intervention by one or more parties. Complainants to this office are often put at a disadvantage in not knowing where and how to pursue an issue if the boundaries of responsibility are not clear. In some cases this confusion extends into the agencies themselves. In these cases it is imperative that agencies define their respective roles through clear procedures and guidelines and liaise with each other frequently on these. The case study Too voluntary shows one such case.

Too voluntary

Mr M was on DSP and was a voluntary job seeker. Mr M complained that DEEWR would not allow him to participate in an intensive employment support program even though DEEWR had referred him to it in March 2007. Mr M had tried to clarify with both Centrelink and DEEWR why he was not able to participate in the program, to no avail.

On contacting Centrelink to investigate his complaint, we established that Mr M's referral to the program stalled because his DSP was cancelled six days before the referral. Centrelink explained that the cancellation occurred due to a systems error which resulted in Mr M's report of earnings not being registered. Centrelink discovered the error and restored Mr M's DSP in April 2007. Centrelink advised us that, while information on payment restoration automatically transfers to DEEWR where job seeking is compulsory, this does not happen for voluntary job seekers. It must be done manually.

Ultimately, although Mr M had been on DSP since May 2006, he had to wait until July 2008 to be eligible for intensive support, an avoidable 12–month delay. In response to our investigation, Centrelink apologised to Mr M, and undertook to update internal reference materials to ensure that future restorations for voluntary job seekers are recorded on the DEEWR system.

Compensation for Detriment Caused by Defective Administration

We have been undertaking an own motion investigation into the administration of the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme by Centrelink, the Australian Taxation Office and the Child Support Agency. The Department of Finance and Deregulation is responsible for the policy underpinning the scheme, and the practices of the other agencies were used to illustrate the complexities and challenges in administering the scheme.

The final report, to be published in August 2009, focuses on the accessibility of the scheme to potential claimants, the treatment of evidence in support of claims, and the moral, rather than legal, obligations which underpin decision making under the scheme but which are often frustrated by a legalistic approach to its administration.

Looking ahead

This year we have been closely monitoring preparations for changes under the same sex legislation and employment service reforms, both of which come into full effect from 1 July 2009. Through regular liaison with Centrelink and stakeholder groups in the community, we have been able to contribute constructively to the identification of issues that may lead to complaints in relation to these changes. We will monitor their implementation closely.

Child Support Agency

Own motion investigations | Complaint themes |

Introduction

The Child Support Agency (CSA) is a program within the Department of Human Services. The CSA has two main functions:

- to make administrative assessments of child support payable by a parent to the person caring for their child (usually the child's other parent)

- to register, collect and transfer amounts payable for child support from the liable parent (the paying parent or payer) to the person with primary responsibility for caring for the child (the receiving parent or payee).

The CSA works in the difficult area of family breakdown, and it is not unexpected that there can be a complaint from one or other party. A particular challenge facing the CSA is to ensure that its processes do not unintentionally inflame or disrupt the relationship between separated parents, or unduly affect the arrangements those parents have made for their support of their children.

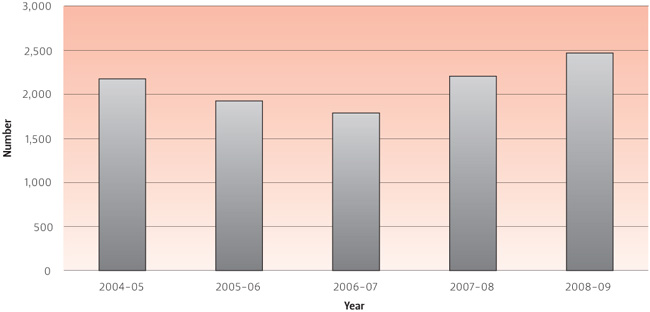

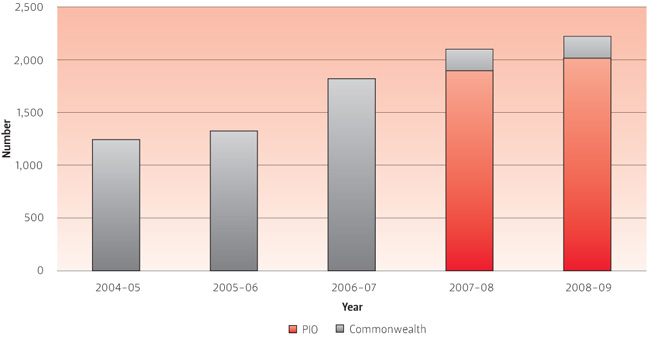

In 2008–09 we received 2,471 approaches and complaints about the CSA. This was an increase of 12% from the 2,208 complaints and approaches we received in 2007–08, and the highest number since 2002–03 (2,515). This increase was greater than for any other major agency. Our analysis of the complaints does not point to any single reason for the continued growth in CSA complaint numbers. We have identified some prominent themes, discussed below. Figure 6.4 shows the trend in approaches and complaints about the CSA over the last five years.

Many of the complaints we receive about the CSA's decisions could be addressed in another way. For example, a parent could lodge an objection to a disputed decision with the CSA or apply to the Social Security Appeals Tribunal for review. The CSA also has an internal complaints service to deal with other matters not subject to review, such as complaints about delay, rudeness, or general service delivery. In general we expect people to use these options before we consider investigating a complaint. Given the complexity of the system, sometimes it is necessary for us to contact the CSA to get a proper understanding of the nature of a person's complaint and the avenues available to the person to address it.

We investigated 29% of the CSA complaints that we finalised in 2008–09. When we investigate complaints, we focus on identifying whether the agency has acted reasonably in the particular case. We assess this in the context of the CSA's role, the relevant legislative framework, and taking into account the circumstances of the payer and payee, and by extension, the children. We also consider whether the complaints we receive indicate any systemic weaknesses in the CSA's processes. We draw such issues to the CSA's attention through the individual complaint, by discussing the broader problem with senior CSA staff in one of our regular meetings, or by conducting an own motion investigation.

FIGURE 6.4Child Support Agency approach and complaint trends, 2004–05 to 2008–09

Own motion investigations

CSA's response to allegations of fraud

In November 2008 we published a report Child Support Agency, Department of Human Services: Responding to allegations of customer fraud (Report No. 12/2008). The report highlighted inadequacies in the CSA's processes for identifying customer fraud, including its arrangements for assessing fraud reported by a member of the public. We made five recommendations. Four recommendations were aimed at improving the CSA's processes in order to better safeguard the integrity of the child support scheme. The other recommendation was for the CSA to reconsider its handling of a specific case, where its failure to investigate a parent's income led to the other parent suffering financial loss.

The CSA accepted all our recommendations about its processes for responding to customer fraud. The CSA also agreed to provide a remedy to the specific complainant, compensating her for her legal costs and refunding the child support that she had overpaid.

Departure Prohibition Orders

In June 2009 we published a report Child Support Agency: Administration of Departure Prohibition Order powers (Report No. 8/2009). This report analysed the CSA's processes for making a Departure Prohibition Order (DPO), which can be used to stop a parent with a child support debt from leaving Australia. The report examined a sample of DPO decisions. We found weaknesses in the CSA's procedures, and deficiencies in each case examined. We made eight recommendations in the report. Six recommendations were aimed at improving the CSA's administration of its DPO powers. We also recommended that the CSA review all the cases where a DPO was in force to ensure that the decision was valid and appropriate, and that the CSA consult with its policy department (the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs) about the suitability of the current arrangements for challenging DPO decisions. The CSA largely accepted the recommendations.

Complaint themes

New child support formula

On 1 July 2008 the legislative formula that the CSA uses to make an administrative assessment of child support changed. Our 2007–08 annual report acknowledged the CSA's thorough preparation for the start of the new formula, including the efforts it made to ensure that its customers were aware of the changes. Our monitoring of CSA complaints in 2008–09 did not suggest any major implementation problems.

We received a small number of complaints that suggested the CSA's computer system was not programmed to handle all the possible variations in the family arrangements of its customers. In at least four cases where the child was in the care of a person other than a parent, the CSA was unable to make an accurate child support assessment promptly. One carer did not receive any child support for nine months because the CSA was unable to make an assessment of the child's parents' liabilities under the formula.

Objection delays

Our 2007–08 annual report noted the CSA's considerable backlog of objections—that is, customer requests for an internal review of a CSA decision. In most cases the CSA is obliged to make a decision on an objection within 60 days of receiving it. In 2007–08 it met this obligation in only about 77% of cases. The CSA introduced new arrangements for the distribution and monitoring of objections, which have reduced the backlog and improved the timeliness of its decisions. The CSA has also built expertise in particular teams that concentrate on specific types of objections, which it says has improved the quality of its decisions. It finalised 85% of objections within 60 days in 2008–09. This is better, but the CSA is still not meeting the timeframe required by Parliament in a substantial number of cases.

Estimate reconciliations

Initially a child support assessment is based on a parent's most recent tax assessment. If the parent's income has reduced, he or she can elect to have the CSA use an estimate of their current income. Once the parent lodges their tax return, the CSA compares the estimate with the tax assessment. If the estimate was too low, the CSA adjusts the assessment. This process is referred to as an 'estimate reconciliation'.

In our 2007–08 annual report we noted that as at 31 March 2008 the CSA had around 200,000 unreconciled estimates. This is an area of ongoing concern. In June 2009 the CSA advised us that it had around 207,000 cases with incomes that needed to be reconciled, and a further 190,000 unreconciled estimates awaiting lodgement of the parents' tax returns. In the 2009–10 Budget the CSA was allocated $85.8 million over three years to complete the outstanding reconciliations. We continue to monitor the CSA's progress in this area.

Failure to collect child support

Around 12% of the complaint issues that we investigated related to the CSA's alleged failure to collect child support. This was the most common issue we investigated, as it was in 2007–08. We consider this is an important part of our role in relation to CSA complaints. For privacy reasons, the CSA is generally reluctant to provide the payee with detailed information about the steps that it has taken to collect outstanding child support and it does not include the payee in any negotiation with the payer to reach a suitable payment arrangement. However, the CSA can provide that information to the Ombudsman's office for the purposes of an investigation. Even though we are not able to pass on all the details to the complainant, we are often able to provide an objective assessment of whether the CSA has taken reasonable action to collect arrears from the payer. In some cases, the CSA will take extra steps following our investigation.

The 2009–10 Budget allocated the CSA $223.2 million over four years to reduce the growth in child support debt and maintain customer service standards. We will continue to monitor the CSA's performance in this area.

Payee overpayments

A payee can be overpaid when the CSA retrospectively reduces the child support assessment, or if by error the CSA paid an amount to the payee without first having received it from the payer. In 1998 this office published a report of its investigation of the CSA's processes for raising and recovering child support overpayments from payees: Child support overpayments—A case of give and take? Following that report, we received few complaints about payee overpayments. This was partly due to changes to the child support legislation, which limited the CSA's power to make a retrospective decision. The CSA also improved its approach to overpayments in response to that report.

This year we started to receive complaints that the CSA had intercepted tax refunds to recover overpayments from people who had previously been payees. Some of these debts were more than a decade old. In some cases the CSA had never provided the person with a written explanation of the debt.

Our investigation of these cases revealed that the CSA had started recovering these old debts after 1 January 2008, when its power to intercept and apply tax refunds to a child support overpayment was reinstated. Approximately 20,000 cases were involved. The CSA has now accepted that it may not always be reasonable for it to recover these debts after such a long delay. In several cases the CSA has agreed to explore the possibility of waiving at least part of the debt because of the circumstances in which the debt arose and the fact that recovery may leave the person worse off than if they had not been overpaid. The case study No deductions shows one such case. The CSA is currently reviewing all payee overpayments over five years old to decide whether it is now appropriate to recover them.

No deductions

Ms N complained that the CSA took her tax refund of $900 in July 2008, without warning, to recover an overpayment that occurred in 1997.

The CSA had paid $4,000 to Ms N as child support in 1996 and 1997. The CSA had notified the employer of Ms N's former husband (Mr O) to deduct these amounts from his salary, and it had made payments to her for the same amounts. In 1997 the CSA reconciled its accounts and found that no deductions had been made, because Mr O had left his job.

In 1997 the CSA told Ms N that she had been overpaid. It negotiated to recover the debt from her ongoing child support payments. The CSA did not send Ms N a statement for the debt or advise her of the balance. When her child support case ended in 2004, she believed the debt was settled. However there was still $2,500 owing.

When Ms N complained to the CSA in 2008 about it taking her tax refund, they acknowledged they failed to provide her with advice about the debt after 2004. The CSA released her tax refund, but said she still owed $2,500.

When we investigated Ms N's complaint, we found that she had been receiving a Centrelink benefit at the time of the overpayment. This payment had been reduced by $1,300 because of the child support that she had been overpaid. She was not able to ask Centrelink to pay her the $1,300 because of the time limits for a person to claim arrears. We pointed out to the CSA that recovering the full amount of the overpayment from Ms N would leave her $1,300 out of pocket. The CSA agreed to our suggestion that it approach the Department of Finance and Deregulation for approval to waive recovery of at least that part of Ms N's debt. The CSA undertook to seek waiver of the entire amount.

Confusing CSA letters

Complainants regularly tell us that they find the CSA's letters hard to understand. Many people find it difficult to follow the CSA's assessment notice, which sets out all the information that the CSA uses to work out the rate of child support, as well as showing the total amount payable. We consider that individual CSA notices are reasonably clear. However, the CSA often sends multiple notices to people, covering different periods. They rarely include a covering letter that clearly explains why they have issued the different notices or what information has changed. In 2008–09 we brought three such cases to the CSA's attention, and asked them to consider how they could present information more clearly to their customers, especially those who have more than one child support case. The CSA has agreed that it should improve its letters to address the problems that we highlighted.

Managing complex cases

Given the sensitive area that the CSA works in, it is important that it carefully considers the possible impact of a decision upon the people who will be affected before it makes that decision. The CSA may need to check its understanding of the facts before it makes a change to a case, to make sure that nothing else has changed. Where it is likely to make a decision with retrospective effect, it should explain any alternatives to the parents before finalising the decision.

Sometimes a simple error can lead to complex problems, as the case study Wrong date shows.

In other cases, agreements and court orders for child support are complicated and can be interpreted in a number of ways with different results. We investigated three complaints about the CSA's administration of complex court orders or agreements. Those complaints suggest that the CSA needs to improve its processes for identifying inherently complex cases, deciding how it will administer them, communicating those decisions to the parents, and advising them of their rights to challenge the decision if they disagree. The case study Fares in lieu shows one example of the difficulties that can arise.

Wrong date

In 2001 Mr P and his former partner made an agreement about the rate of child support that he would pay for their children. The CSA accepted the agreement and issued an assessment for the agreed amount. The agreement was to last for three years, with annual updates for inflation.

The CSA adjusted the assessment each year as required by the agreement. However, it made a mistake one year and changed the end date of the agreement to the date the youngest child would turn 18. Neither Mr P nor his former partner realised the mistake. Mr P paid child support to the CSA each month according to the CSA's assessment and the CSA transferred the money to his former partner.

In June 2008 the CSA rang Mr P to tell him that it had discovered the agreement should have ended in 2004, and that the usual child support formula would apply to his case from that date. The CSA officer told him that he now owed the CSA an additional $37,000. He later received notices from the CSA which advised that he actually owed more than $65,000.

Mr P complained about the CSA's failure to give him advance notice of the intended change. He said that the care arrangements for the children had varied since he and his partner made the agreement, and that he had made a number of payments that the CSA could have credited against his debt. These would affect the accuracy of the CSA's decision. He said that the CSA did not give him any advice about his options, or even an opportunity to tell them about these matters.

During the course of our investigation, the CSA allocated a special case officer to Mr P and his partner to assist them to work through their child support options. As a result, Mr P's debt was reduced substantially. We advised the CSA that we considered that the earlier process it followed for correcting the error was not appropriate, given the time that had passed and Mr P's reasonable reliance on the CSA's advice of what he was required to pay.

Fares in lieu

Mr Q and his former wife obtained court orders about residence and contact for their children, in anticipation of the children moving interstate with their mother. As part of the proceedings, they agreed that Mr Q would pay the cost of the children's airfares for their contact visits with him. The agreement stated that these payments were 'in lieu of child support payments'.

Mr Q provided a copy of the agreement to the CSA after it issued an assessment of child support payable by him. The CSA considered the agreement and decided that it would administer it by crediting any amounts that Mr Q paid for airfares against what he had been assessed to pay under the child support formula. Mr Q was still liable to pay any difference to the CSA. Mr Q complained repeatedly to the CSA about this interpretation. He said that he and his former wife intended that he would only have to pay the cost of the children's airfares, and not be liable for any additional child support.

We investigated Mr Q's complaint. We found that although the CSA had considered the interpretation of the agreement on several occasions, it had never provided Mr Q and his former wife with advice about its decision in a form that they could object to, nor any advice about their rights in this regard. The CSA accepted our finding that the process it had followed had been deficient and undertook to advise the parties of their objection rights. The CSA told us that it was already in the process of delivering training to its staff about interpreting court orders and agreements, and that it would review its procedural instructions to ensure that they emphasise the need to provide customers with written advice of the interpretation and their right to object to it.

Interaction between family tax benefit and child support

The child support scheme interacts with, and can affect, some payments administered by Centrelink. For example, a person must take 'reasonable maintenance action' for a child after separation, in order to qualify for additional family tax benefit (FTB) for that child. In most cases, 'reasonable maintenance action' involves applying to the CSA for an assessment of child support, and either collecting 100% of the assessed amount privately from the other parent or applying to the CSA for collection.

In most cases, Centrelink advises an FTB recipient or applicant about the requirement to apply to the CSA for an assessment of child support payable by their former partner/child's parent. The trigger for that advice is usually when the person tells Centrelink that they have separated, or that they now have care of a child. The CSA and Centrelink also share certain information about changes of care for children, or when FTB or child support is cancelled. Each agency reviews their records when they receive advice about a change in the other agency's records, to see if they need to amend the case. Any failure in those liaison and review arrangements can lead to substantial detriment to a parent with care of a child.

We investigated a number of complaints about the interaction between the CSA and Centrelink in relation to the reasonable maintenance action test. These complaints revealed a range of problems, including a lost opportunity to receive child support, a person receiving a reduced rate of FTB, and a liability to repay substantial amounts of FTB to Centrelink. In some cases Centrelink decided to waive recovery of the FTB debt and the CSA considered paying compensation to the payee for their lost opportunity to receive child support. We intend monitoring this problem in the coming year.

CSA's 'capacity to pay' investigations

The CSA's 'income minimisers' project is one way in which it seeks to ensure the integrity of the child support scheme. This project targets cases where a parent's taxable income is not a true indicator of their capacity to support their children, either because of the way their financial arrangements are structured (including some legitimate arrangements for tax purposes), or because they are involved in the 'cash economy'. If the CSA believes that the parent has a greater capacity to pay, it can start a process to change the assessment, which includes an investigation into the parent's capacity to pay.

We have investigated several complaints which raised concerns about the CSA's processes for managing personal information in the course of these investigations, including information about related people, such as a parent's new partner. We will conduct a more detailed investigation of the CSA's 'capacity to pay' process in 2009–10.

Defence

Department of Defence | Australian Defence Force | Department of Veterans' Affairs | Defence Housing Australia

introduction

Our office investigates complaints about a range of defence agencies, including the Department of Defence, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) (Royal Australian Navy, Australian Army, Royal Australian Air Force), the Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) and Defence Housing Australia (DHA).

We investigate these approaches as either the Commonwealth Ombudsman or the Defence Force Ombudsman (DFO). The DFO investigates complaints that arise out of a person's service in the ADF, covering employment–related matters such as pay and entitlements, terminations or promotions. As Commonwealth Ombudsman, we investigate other administrative actions of these agencies.

In 2008–09 we received 609 defence–related approaches and complaints, compared to 562 in 2007–08. This represents an 8% increase in complaints.

TABLE 6.1Defence–related approaches and complaints received, 2004–05 to 2008–09

Agency | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Australian Army | 190 | 169 | 145 | 138 | 141 |

Defence Housing Australia | 28 | 29 | 36 | 28 | 43 |

Department of Defence | 165 | 138 | 106 | 135 | 157 |

Department of Veterans' Affairs | 216 | 276 | 256 | 139 | 160 |

Royal Australian Air Force | 69 | 80 | 57 | 48 | 45 |

Royal Australian Navy | 78 | 54 | 50 | 59 | 49 |

Other (see breakdown for 2008–09 in Appendix 3) | 12 | 4 | 20 | 15 | 14 |

Total | 758 | 750 | 670 | 562 | 609 |

Department of Defence

We received 157 approaches and complaints about the Department of Defence in 2008–09, compared to 135 in 2007–08. Of the complaints we investigated, the three main sources of complaint were:

- recruitment into the ADF

- the payment of financial compensation

- applications for honours and awards.

The number of complaints we investigated about honours and awards increased from 2007–08. Because the eligibility requirements for specific honours and awards are clearly set out in ministerial determinations and letters patent, our investigations normally focus on the accuracy of Defence's application of those rules to an individual's circumstances. The main cause of complaint to our office was where Defence had declined to give an award on the basis that its records showed the member was not eligible. However, the member believed that Defence's records did not accurately reflect their service.

In almost all of these complaints, investigation was made more complicated by the length of time that had passed. Many of our complaints related to service in the ADF more than 30 years ago. In the absence of supporting records to confirm a person's service, we do not believe that denying an honour to a member is unreasonable. However, in some cases alternative documentation and records are enough to reasonably establish a member's entitlement, as the case study Officially not there shows.

We do not normally investigate the reasons for establishing a certain award, or the limits of the eligibility criteria. These policy issues are more appropriately dealt with by the new Defence Honours and Awards Tribunal, which is an independent body set up to consider issues arising in the area of Defence honours and awards. In July 2008 the Government appointed the first members to the Tribunal. The inaugural chair, Emeritus Prof. Dennis Pearce AO, is a former Commonwealth and Defence Force Ombudsman.

Officially not there

Mr R considered he was entitled to the Australian Service Medal, as he served for more than 30 days in Malaysia in 1988. The Central Army Records Office had no record of Mr R serving in Malaysia, and the Directorate of Honours and Awards refused Mr R's application. After investigation by our office, Defence reviewed his application and accepted the statutory declarations by colleagues who testified that they served with him in Malaysia. A decision was then made to award Mr R the Australian Service Medal with Clasp 'SE ASIA'.

It seemed that Mr R's deployment was as a last–minute replacement for another ADF member, and was not officially recorded. Our office also investigated whether Mr R had suffered any detriment to his pay and allowances by not being officially recorded as being in Malaysia at that time.

Australian Defence Force

We received 235 complaints from serving and former members about the actions and decisions of the Royal Australian Navy, Australian Army and the Royal Australian Air Force, compared to 245 in 2007–08.

Of the complaints we investigated, the most frequent cause of complaint was about the ADF's internal complaint system, the redress of grievance (ROG) process. The ROG process has been the subject of much debate and inquiry over the past 10 years. In May 2008 the regulations governing the redress process were changed. One of the main changes was the introduction of a time limit of 90 days for a commanding officer to investigate and decide on a member's grievance. This was an important change.

If a member is not satisfied with the commanding officer's decision, the member may refer the matter to the Chief of their service. There is no time limit for consideration by the Chief, and we are receiving an increased number of complaints about delay. The delay usually occurs in the preparation of a brief prior to the Service Chief's decision, as the case study Four of the same shows.

Four of the same

Within a few days in February 2009 we received four separate complaints by four Army members who had requested their ROG be referred to the Chief of Army. The requests had been made in July, August and September 2008. When we asked Defence about the status of these ROGs, we learned that none of the referrals had yet been allocated to a case officer. Two were due to be allocated in March 2009, and two were unlikely to be allocated before June 2009.

Although we consider these delays to be unreasonable, we were unable to recommend that any of the complaints be given priority over any other complaints in the queue. Instead, we decided to question the processes and systems used by Defence, with the aim of improving timeliness for all redresses that have been referred to the Service Chief. This is ongoing.

We raised our concerns about the delays with the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade in June 2008, in its public hearings to gather evidence for its fourth progress report into the reforms to Australia's military justice system. We were also consulted by the Honourable Sir Laurence Street AC, KCMG, QC and Air Marshal Fisher AO (rtd), who were appointed by the Chief of the Defence Force (CDF) to conduct a review into the effectiveness of the overhauled military justice system. The delays in the ROG process were noted in Sir Laurence and Air Marshal Fisher's Report of the Independent Review on the Health of the Reformed Military Justice System, released in March 2009.

We are concerned that the excellent structural and process reforms that have been put in place in the last few years are in danger of being undermined by this single bottleneck. Our experience shows that confidence in an internal complaint system is essential. If confidence is lost because there is seen to be excessive delay at any stage, then the system will not be used.

The Ombudsman wrote to the CDF in June 2009, drawing his attention to our assessment of the potential pitfalls. We noted that the ADF put considerable effort into ensuring that decisions were beyond reproach. We queried with the CDF whether this thoroughness should be consciously balanced against the dangers of excessive delay.