Commonwealth Ombudsman - Annual Report 2009-2010 - Chapter 5

Chapter 5

On this page

- Agencies overview

- Commonwealth Ombudsman

- Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

- Centrelink

- Child support agency

- Comcare

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

- Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

- Fair Work Ombudsman

- Department of Health and Ageing

- Medicare

- Freedom of information

- Monitoring and inspections

- Overseas students

- Defence Force Ombudsman

- Department of Defence

- Department of Veterans' Affairs

- Defence Housing Australia

- Immigration Ombudsman

- Immigration and Citizenship

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- Australian Federal Police

- Australian Crime Commission and Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

- CrimTrac, AUSTRAC and Attorney-General's Department

- Postal Industry Ombudsman

- Taxation Ombudsman

- Australian Taxation Office

- Australian Prudential Regulation Authority

- Australian Securities and Investments Commission

- The Treasury

- Feature: Good › better › best

Agencies overview

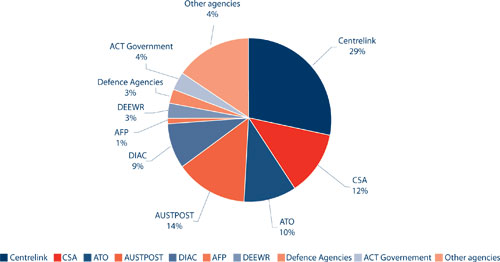

Most of the approaches and complaints received by the Commonwealth Ombudsman about Australian Government agencies within the Ombudsman's jurisdiction (81%) related to the following agencies:

- Centrelink—5,199 approaches and complaints

- Child Support Agency—2,280 approaches and complaints

- Australian Taxation Office—1,810 approaches and complaints

- Australia Post—2,626 approaches and complaints

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship —1,600 approaches and complaints

- Australian Federal Police—219 approaches and complaints

- Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations—479 approaches and complaints

- Defence agencies—578 approaches and complaints.

This chapter assesses our work with these and other agencies in handling complaints and dealing with other broader issues during 2009–10. It discusses the way agencies deal with freedom of information requests and the monitoring and inspections work we undertake.

It also looks at other areas of the Ombudsman's work:

- as Defence Force Ombudsman, dealing with complaints by current and former members of the Australian Defence Force

- dealing with complaints about the Australian Federal Police, including under the role of Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- as Immigration Ombudsman, including dealing with complaints from people in detention

- the broader Postal Industry Ombudsman role

- complaints about taxation as the Taxation Ombudsman

- with overseas students.

Figure 5.1 shows the number of approaches and complaints received in 2009–10 about agencies within the Ombudsman's jurisdiction. Detailed information by portfolio and agency is provided in Appendix 3— Statistics .

Figure 5.1: Approaches and complaints received about, within jurisdiction, agencies, 2009–10

Commonwealth Ombudsman

Australian Customs and Border Protection Service

The Ombudsman received 99 complaints about The Australian Customs and Border Protection Service in 2009–10, a small increase on the 94 received in the previous year. The main themes of complaint were:

- the processing of passengers at Australian international airports

- actions relating to the import or export of goods.

A common complaint made by those who have interacted with Customs and Border Protection at an airport is that they were not told why they were questioned or why their baggage was searched. Complainants often questioned whether an officer had the power to take the particular action.

One of the tasks of this office in responding to such complaints is to balance two competing public interests: transparency and accountability in government processes, against the protection of sensitive information about investigation and detection methods used by the agency.

Customs and Border Protection officers exercise strong coercive powers in the airport environment and their interventions can be seen as intrusive and unduly personal. Officers routinely stop and question travellers and examine goods in their possession including diaries, mobile phones, cameras and computers. Officers can copy documents found in a passenger's possession and, in some circumstances, retain items for further examination.

In examining complaints received we also looked at the information that Customs and Border Protection makes available about travellers' rights and responsibilities and how a grievance can be made or redress sought.

Lack of information about making a complaint

Mr A complained to this office about questioning and baggage examination by a Customs and Border Protection officer. He claimed that officers failed to assist him when he wished to make a complaint at the airport, and that there was inadequate information at the airport about a traveller's right to make a formal complaint.

Our investigation identified that while Customs and Border Protection has a comprehensive complaints process, it is not supported by clear guidance to officers about how to handle complaints made at airports. A brochure explaining the complaint process is available in some areas within airports, however display of the brochure is limited and officers are not required to provide it when a traveller raise a grievance.

Customs and Border Protection agreed that several aspects of the initial complaint process at airports could be improved and is in the process of developing new guidelines to resolve this issue.

We look forward to working with Customs and Border Protection on improving its complaint-handling processes and making the information on avenues of complaint more accessible to passengers.

Penalties for a ring

Customs and Border Protection determined that GST was payable on a ring found in Ms B's luggage. She had not declared the ring and Customs and Border Protection imposed taxes and penalties totalling more than $1,000. It impounded the ring when Ms B was not able to pay and issued a notice to her that if she was dissatisfied with the decision, she could ‘lodge a taxation objection with the Commissioner within the specified periods'. The letter did not identify the Commissioner, provide the Commissioner's contact details or state the relevant period. Through her own enquiries, Ms B identified that the notice was referring to the Commissioner for Taxation. However, when she lodged a statement saying she would pay the GST but not the penalty, the ATO referred the matter to Customs and Border Protection because the objection was about the penalty. It reviewed the matter and upheld the penalty.

As a result of our enquiries, Customs and Border Protection reviewed the penalty again and reduced it. We formed the view that Ms B's review rights were not adequately explained. Customs and Border Protection acknowledged that the process should be made clearer, and discussed the objection process with the ATO. It has since updated the online content of the 'Notice of Goods Impounded and/or Tax Assessed' form to include information about the ATO's contact details. It also advised that new forms would be available that include revised guidelines for making objections.

The increased volume of information (and methods of storing information) that travellers now have available to them adds to the complexity of the Customs and Border Protection officer's role. Complaints to this office have often concerned an officer's power to examine laptops, memory cards and other electronic devices containing large amounts of data, including photographs, financial records, contact details and other information that the person considers to be personal. In this context, the lawful and fair exercise of powers is increasingly important.

Copying a passenger's documents

Mr C's baggage was examined twice by Customs and Border Protection officers in a three-week period. Relying on information already available to them about Mr C, the officers stopped him so they could copy documents he was carrying. Our investigation identified that this was an invalid exercise of an officer's power. Customs and Border Protection accepted our assessment, and reinforced with its officers the circumstances that must exist to allow them to copy documents found in a traveller's possession.

Another complaint highlighted the need for consistent and correct record keeping before pursuing a debt. It also highlighted that systems need to be in place so that any issue over outstanding amounts can be resolved as soon as possible. The longer the time taken to follow up an unresolved debt, the more difficult it becomes to satisfactorily resolve the complaint.

Pursued for an overdue fine

Mr D complained to our office about action being taken by Customs and Border Protection in October 2009 to recover an $8,000 fine that was issued in 2007. Mr D contacted Customs and Border Protection to explain that the fine had been paid in full in 2007. Customs and Border Protection believed that $500 remained outstanding and Mr D had to provide evidence to verify payment. Mr D advised Customs and Border Protection that the only record he had was his cheque book balance, and to obtain further evidence he would need to pursue the matter with his bank.

Mr D's records showed a payment of $500 had been made to Customs and Border Protection's Perth office. Once it had received that information, Customs and Border Protection checked its records and acknowledged the payment had been made but had not been reconciled with its Debt Management Area. It withdrew its request for payment, apologised to Mr D and undertook to improve its processes.

During the year the Ombudsman commenced an own motion investigation into Customs and Border Protection's administration of some of its coercive powers in passenger processing. The investigation will assess Customs and Border Protection's policy and practice against legislation and principles of good administration, and in light of best practice principles set out by the Administrative Review Council. A report on the investigation is expected to be published in November 2010.

Centrelink

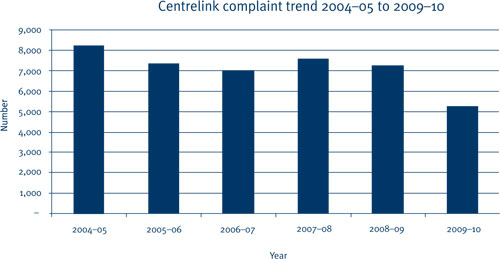

In 2009–10 the Ombudsman's office received 5,199 approaches and complaints about Centrelink compared to 7,226 in 2008–09. This is a 28% decrease over the previous year and the lowest number in 10 years. The figure also includes 49 cases relating to the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER).

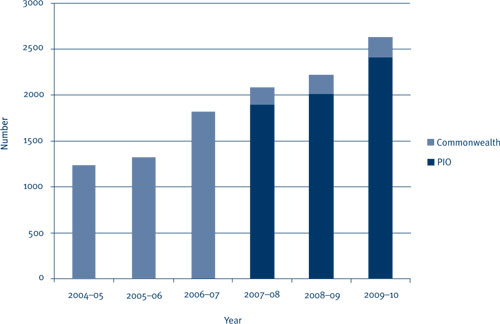

Despite the decrease, Centrelink continues to be the agency about which the Ombudsman receives the highest number of complaints. This is not unexpected given the high volume of transactions, the breadth and complexity of the services and payments that Centrelink delivers on behalf of Australian Government agencies. Figure 5.2 shows the trend in approaches and complaints over the past five years.

Figure 5.2: Centrelink complaint trend 2004–05 to 2009–10

Complaint themes

Although a number of factors are likely to have contributed to the reduction in Centrelink complaints, the absence of any stimulus or bonus payments (which generated large numbers of complaints in recent years) and the implementation of a more flexible social security compliance framework, appear to have contributed to the significantly lower figure.

Procedural fairness

Over the years, the Ombudsman's office has received complaints from customers about payments being suspended and/or debts being raised on the basis of wrong information. In many cases, Centrelink has not told these customers about the information it relied upon in deciding to suspend a payment or raise a debt, and therefore has not given them a chance to correct or provide more complete information.

An example of this can be seen in the case study, P rocedural fairness in decision making.

Procedural fairness in decision making

Centrelink suspended Mrs E's parenting payment because it had identified that Mr E was transferring large sums of money through his bank accounts. Centrelink intended to investigate why these amounts had not been declared as income. Mrs E complained to this office about the suspension of her payment without warning or an opportunity to explain their circumstances. Centrelink subsequently learned that Mr E's accounts were being used as holding accounts for funds that were being transferred internationally for aid reasons, and that Mr and Mrs E derived no benefit from these transactions. As a result, Centrelink restored Mrs E's payments with arrears. Our office formed the view that Mr and Mrs E had been denied procedural fairness.

Transfer to more suitable payment

Previous Ombudsman reports have highlighted the effectiveness of analysing complaints from individuals to identify whether the same issue affects a larger number of existing or potential customers. Our focus on identifying systemic problems has continued this year. An example of this approach can be seen in the case study, Transfer to age pension.

Transfer to age pension

We received a complaint from Ms F that Centrelink had not transferred her to the age pension (AP) when she reached age pension age in 1998. Ms F was on a lower payment until transferring to AP in 2009 and asked for a review of the start date of her AP (back to 1998). Centrelink decided that it could treat Ms F as having transferred to AP when she originally reached age pension age, and paid her arrears for the amount she had missed out on.

While investigating Ms F's complaint, we asked Centrelink about whether other customers had remained on a lesser payment despite reaching age pension age. We were advised that approximately 1,800 other customers had been identified as receiving another income support payment despite having reached age pension age and that Centrelink had subsequently invited those customers to apply for AP. We will continue monitoring this issue during 2010–11 to ensure that these customers are not disadvantaged.

Cross-agency issues

Many complaints to our office require us to make enquiries of more than one agency. This is particularly the case where one agency is responsible for delivering a product or service, while another has responsibility for the relevant policy or law.

Complaints that involve more than one agency can be particularly difficult to resolve. This challenge is evident in the case study Medicare or Centrelink FAO service?

Medicare or Centrelink FAO service?

Both Centrelink and Medicare Australia deliver services on behalf of the Family Assistance Office (FAO). Ms G complained to our office that the wording used in an FAO letter had caused her offence and confusion. Our investigation confirmed that the letter appeared to be inaccurate and confusing, and we suggested that Centrelink apologise to Ms G. Centrelink advised that the letter in question had been issued by Medicare and, as such, it would be more appropriate for that agency to apologise. We contacted Medicare to seek an apology and, following protracted discussions with both Medicare and Centrelink, eventually Medicare apologised to Ms G. It took nine months for the two agencies to agree who was responsible and take action to resolve Ms G's concerns.

In some instances the business of one agency can be affected by system errors or failures on the part of another agency, often to the detriment of the customer. An example of this can be seen in the case study, Cross-agency errors—FaHCSIA, Centrelink and ATO.

Cross-agency errors—FaHCSIA, Centrelink and ATO

During 2009–10 the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) undertook a major upgrade of its information technology systems. The upgrade affected the ATO's ability to advise Centrelink that it had received tax returns. Also during this time, the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) implemented a policy which saw customers have their Family Tax Benefit (FTB) suspended if they failed to lodge past year tax returns. The Ombudsman's office subsequently received a number of complaints from Centrelink customers whose FTB payments had been suspended because Centrelink's records indicated they had not lodged their tax returns. We encouraged these complainants to provide copies of their completed returns to Centrelink so that their payments could be manually restored pending receipt of official confirmation from the ATO.

Reports

Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration

In August 2009 the Ombudsman's office released its own motion investigation report into the administration of the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme. Under the scheme, the Ombudsman has a specific capacity to make recommendations that agencies reconsider cases where compensation has been refused.

The report focused on the handling of CDDA claims by Centrelink, the ATO and the Child Support Agency, but made recommendations relevant to all agencies handling CDDA matters. Since the publication of the report, the assessment of CDDA cases by Centrelink has improved. However, the office continues to be concerned about the lack of awareness of the scheme generally, particularly amongst non-government organisations representing people who are vulnerable to the effects of poor government administration.

Economic Security Strategy Payment

Our 2008–09 annual report reflected on the large number of complaints our office had received about the assessment of claims for the Economic Security Strategy Payment (ESSP). In November 2009 the Ombudsman's office released its report into the administration of the ESSP. The report focused on the broader lessons for policy departments for improving how they communicate about, and administer, payments to be delivered within tight time frames.

Review of circumstances leading to a fraud conviction

In May 2010 the Ombudsman's office released an investigation report into the handling of a fraud matter by Centrelink and the Commonwealth Department of Public Prosecutions. The Ombudsman's report identified that both agencies relied on incomplete and inaccurate information in deciding to pursue prosecution against the customer. We expressed the view that, but for these errors, legal action and a conviction against the customer may not have eventuated. The report made recommendations for the agencies involved to provide redress to the individual customer, and to revisit their handling of her case and other similar fraud matters.

Reviews and delays

Our 2008–09 annual report noted continuing concerns with Centrelink's internal review processes and advised that we expected to release an own motion investigation report in 2009–10. This report has been completed and should be published before the end of 2010.

Engagement

In addition to investigating individual complaints, the Ombudsman's office has an important role in improving public administration. By maintaining regular, robust liaison with Centrelink during 2009–10 our office has been able to ensure it is informed of planned changes to social security and family assistance law and policy, provide input into how these changes might be implemented and communicated to customers. For example, we provided feedback to Centrelink about the way in which the same-sex reforms were communicated to customers who might be affected by them.

We also meet regularly with Centrelink to keep abreast of progress in changes to policy or operations that have resulted from Ombudsman recommendations. One example is the Government revisiting its approach to delivering payments to customers with acute or terminal illnesses.

Looking ahead

Same-sex initiatives

From 1 July 2009 Commonwealth legislation was revised to remove discrimination against same-sex couples. While most changes provided beneficial outcomes, in some cases in the social security and family assistance arenas, these changes had the potential to reduce or cancel the entitlements payable to some couples and families.

Early in 2010 the Government announced that Centrelink staff would take a ‘compassionate approach' to raising or recovering debts resulting from these legislative changes. Centrelink acknowledged that fears of discrimination could result in same-sex relationships not being declared. The Ombudsman was able to advance procedural instructions to support more consistent outcomes and will continue to engage with Centrelink on these matters.

Acute and terminal illness

In March 2009 the Ombudsman's office released an own motion investigation report into the assessment of claims for disability support pension (DSP) from people with acute or terminal illnesses.

Following our report, the government announced that from March 2010 customers with a serious illness receiving an activity-tested payment could be granted a long-term exemption from activity testing. It also means that there are fewer reporting requirements that involve a job capacity assessment or repeated medical certificates.

Given the short time frame in which the new policy has been in place, we have not yet had an opportunity to assess the impact on customers.

Mental illness—servicing vulnerable customers

In 2009 we commenced an own motion investigation into the engagement of customers with a mental illness in the social security system. The investigation focused on the services delivered and overseen by Centrelink, the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations and FaHCSIA in response to feedback from customers, carers, non-government organisations and agency staff that some customers with a mental illness have difficulty navigating the social security system.

Our investigation, Falling through the cracks , examines the effectiveness of current government policies and procedures as they affect customers suffering from a mental illness. The report should be published in second half of 2010.

Child support agency

The Child Support Agency (CSA) is an organisational unit within the Department of Human Services. In 2009–10, the Ombudsman received 2,280 approaches and complaints about the CSA, a decrease of 7.8% from the previous year. Approximately 28% of complaints were investigated.

Complaint themes

Complaint themes in 2009–10 included debt management, ‘care percentage' decisions used in child support assessments, and a backlog in income reconciliations.

Collecting child support debts

The biggest area of CSA debt recovery is the collection of child support payable by payers for transfer to payees. However, the CSA also recovers overpaid child support from payees. A payee can be overpaid when the CSA retrospectively reduces the child support assessment, or if by error the CSA paid an amount to the payee without first having received it from the payer.

CSA's debt enforcement method accounted for 14% of complaint issues, and was the largest investigated issue category. Almost as many complaints related to the CSA's failure to collect (13.5%).

Debtors complain to us about the harshness of the CSA's collection action and question the accuracy and fairness of the debts. Those relying on the CSA to collect debts and transfer money to them complain that the CSA is too lenient, or is not taking sufficient enforcement action. They may be frustrated by the CSA's unwillingness to provide detailed or regular information about its efforts. By investigating these complaints we can independently confirm the reasonableness of the CSA's actions, or alternatively, uncover and seek remedies for delay or inaction.

In 2009–10 we investigated three cases where the CSA had collected late payment penalties from a payer's tax refund despite having agreed to cancel the penalties when the person had paid off their child support debt. We were concerned that the CSA's processes allowed this to happen and seemed to prevent the debtor from exercising their objection rights. The CSA has now refunded those penalties. In another case the CSA continued to charge late payment penalties on a debt that a court had suspended. We will continue to monitor the CSA's administration of late payment penalties in 2010–11.

‘Care percentage' decisions

We identified a pattern of complaints about the CSA's administration of the rules for deciding what ‘care percentage' to use for each parent when calculating child support, including delays, confusing advice and, in some cases, a lack of understanding on the part of CSA staff of the complex rules that applied from 1 July 2008. At the same time, we noted that the rules used by Centrelink to work out a parent's level of care for Family Tax Benefit (FTB) did not seem to cause the same problems.

In the 2009–10 Budget, the Government announced that from 1 July 2010, it would align the CSA and Centrelink rules for working out care percentages (the ‘alignment of care' measure). In preparation we met with policy officers in FaHCSIA to highlight the problems we had identified in complaints. Many of those problems appear to have been addressed by the alignment of care measure; however, we will continue to monitor this area of the CSA's administration.

Income reconciliations

Last year we reported significant delays in the CSA reconciling parents' estimated incomes against the Australian Taxation Office's (ATO) assessments. This backlog arose from system problems and resourcing decisions within the CSA, not the ATO. As at 30 June 2010, the CSA reported having reconciled 249,732 estimates, with approximately 143,000 remaining. A change in child support law from 1 July 2010 will overcome the need for the CSA to manually calculate every estimate reconciliation. The CSA expects to complete the backlog of estimate reconciliations by 30 June 2011.

The CSA's reconciliation of a parent's income can lead to an additional child support debt for the payer or an overpayment of child support for the payee. If they have not kept detailed records of their income, the person whose income has been reconciled may not be able to challenge the CSA's decision. This was a problem in one complaint where the CSA reconciled a parent's 1999 income years later, in 2010. Lengthy delays like this mean that statutory time limits for the Change of Assessment (CoA) process and court applications for leave to apply for a CoA have often expired.

These statutory time limits can also have unfair results for one parent when the other parent lodges a late tax return showing that their income was less than the CSA had used in working out child support. Two complainants to this office have been required to repay money to the CSA that they received in good faith and have no way to challenge. We have recommended that the CSA assist these complainants to prepare an application to the Department of Finance and Deregulation for these debts to be waived.

The CSA's interaction with other Commonwealth agencies

The CSA and Centrelink share information to ensure that people receiving the higher rate of FTB for a child of a previous relationship also have a current child support assessment for that child. The following case shows how a CSA error can flow on to affect a person's FTB.

The CSA and the ATO share information required to administer the child support scheme. Sometimes, the automatic exchange of information is not enough. The case study Caught in the wheels shows that it can sometimes be difficult to get the two agencies to communicate with each other.

Little mistakes with serious consequences

A particular challenge facing the CSA is to ensure that its processes do not harm the relationship between separated parents. A small slip-up can have serious repercussions, as in the case study A trail of errors.

Computer says no!

The CSA mistakenly deleted Mrs H's child support case for her daughter from its system. It told Mrs H it would take up to three months to fix this problem. Based on a computer match shortly afterwards, Centrelink advised Mrs H that she had been overpaid $9,000 in FTB. Centrelink's decision was based on records that showed no child support assessment since 2005.

Mrs H and the CSA told Centrelink about the error. Centrelink said that it would cancel the overpayment when the CSA fixed the mistake, but in the interim, it would deduct $60 per fortnight from her FTB for the overpayment. Mrs H complained to the Ombudsman but it still took almost two months for the CSA problem to be resolved and for Centrelink to cancel the overpayment and refund the deductions to Mrs H.

Caught in the wheels

The CSA asked Mr J to pay a child support debt based on an incorrect ATO assessment. Mr J told us that although the ATO had since amended its assessment, the CSA refused to update his child support unless he could prove that the assessment was incorrect because of an ATO mistake.

We recommended that the CSA provide Mr J with a letter to the ATO explaining the information the CSA needed and why. The CSA did this, but the ATO refused to give Mr J a letter to take back to the CSA. Only at our request did the CSA contact the ATO to get the information it needed and amend Mr J's child support assessment, cancelling the incorrect debt.

A trail of error

Ms K was a child support payee with a fear of domestic violence from her former partner, Mr L. The CSA discovered that Mr L had underestimated his income for his child support assessment and asked him to pay arrears. Ms K was afraid that Mr L would force her to give back anything that the CSA collected for her. She spoke to a Centrelink social worker about her situation, then instructed the CSA to cancel her child support assessment and Mr L's arrears.

The CSA paid Ms K $600 that it had intended to refund to Mr L. Ms K contacted the CSA to find out whether she should return it. The CSA told Ms K that she could keep it: Mr L might not know she had received the money and he would probably think the CSA had kept it. Ms K complained to the Ombudsman about this advice, as she was not sure what to do. She suspected that Mr L knew the CSA had paid the money to her and was afraid of what might happen if she attempted to conceal this from him. Our investigation of Ms K's complaint achieved the following:

- we were able to confirm for Ms K that Mr L was aware that she received the money, making it easier for her to handle any consequences

- the CSA advised Mr L that it had been ‘remiss' in paying $600 to Ms K and invited him to apply for compensation

- the CSA acknowledged the sensitive nature of Ms K's case and apologised to her

- the CSA re-examined the breakdown in its procedures and identified a system improvement to reduce the risk to other vulnerable payees.

Reports

Own motion investigations and submissions about the CSA

This year we published a report, Australian Federal Police and the Child Support Agency, Department of Human Services: Caught between two agencies: the case of Mrs X (report 14|2009) . The Ombudsman also made a written submission to an independent review of the CSA's administration by Mr David Richmond AO, Delivering Quality Outcomes.

In 2009 we commenced an own motion investigation into the CSA processes and practices involved in accessing a parent's ‘capacity to pay'. Another own motion investigation commenced in 2009 relates to ‘write only' procedures, which limit service to customers who display difficult and challenging behaviour. Both investigation reports are due for release in the second half of 2010.

Improved timeliness for CSA objections

We have previously reported our concern about the CSA's failure to finalise its internal reviews, known as objections, within the 60-day period set by law. In 2009–10, results significantly improved and compliance is now nearly 100%.

Better Departure Prohibition Order procedures

The CSA can stop a person who owes arrears of child support from leaving Australia by making a Departure Prohibition Order (DPO). In June 2009, the Ombudsman released a report Child Support Agency: Administration of Departure Prohibition Orders (Report No 8/2009) with eight recommendations, which the CSA has implemented. The CSA now has better DPO procedures and its letters contain a comprehensive list of appeal rights and options to challenge a DPO.

Comcare

Comcare regulates workers' compensation and work health and safety. The majority of complaints received by our office about Comcare concern its management of claims from injured workers. During 2009–10 our office received 72 complaints about Comcare, down from 95 the previous financial year, representing a 24% decrease.

Comcare will often need to consider a range of medical information when making decisions regarding eligibility for compensation. This can prolong the time taken to make a decision, which is a source of frustration for complainants. During 2009–10 the office was able to assist complainants by ensuring any unnecessary delays were addressed and facilitating better explanations of decision processes.

The investigation of two complaints about Comcare highlighted a gap in its ability to fully compensate claimants who had suffered a financial loss due to administrative error. In both cases the complainants had originally missed out on their proper entitlement due to an error in calculation. The mistakes were undetected in one case for 13 years, and 10 years in the other. Upon discovering the error, Comcare paid the amount originally owed, but determined that under its legislation it could not pay interest on that money.

Although the office accepted that the payment of interest in these cases was problematic under Comcare's legislation, the Ombudsman issued a report (report 4|2010) recommending that Comcare give further consideration to the issue of compensation for the two complainants. The Ombudsman also recommended that Comcare consider how it could address similar claims in the future.

In response, Comcare found a way to fully compensate one of the complainants and has indicated that it hopes to at least partially compensate the other. Comcare has also given the office an undertaking to develop and seek approval for a scheme to deal with future claims for compensation caused by its defective administration. It is hoped that such a scheme will enable the complainant who has only been partially compensated to receive their full entitlement.

It is pleasing to note that after the report was issued, Comcare undertook its own review to ascertain if there were other similar cases. While the review has not identified any further underpayments, Comcare's proactive response to the report is a good example of how an agency can use feedback from individual complaints as an opportunity to improve customer service more generally.

Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations

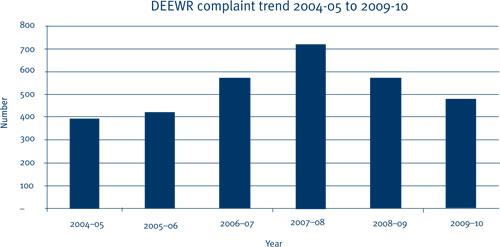

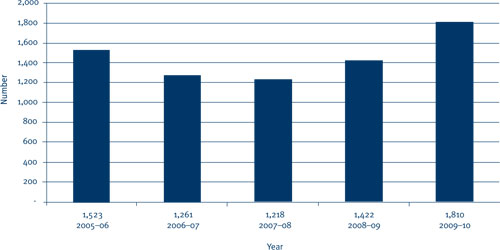

In 2009–10 the Ombudsman's office received 479 approaches and complaints about the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR). This is a 16% decrease from the 571 approaches and complaints we received in 2008–09. Figure 5.3 shows complaint trends over the past five years. The number of approaches and complaints received about DEEWR during 2009–10 was the lowest in the past four years, and sees a return to the level of complaints received prior to the implementation of the Welfare to Work social security reforms.

Figure 5.3: Complaints received for the period 2004–05 to 2009–10

Complaint themes

As part of our ongoing work in looking at complaint trends and themes, we engaged with DEEWR to discuss issues about individuals as well as broader groups of customers, and to make recommendations for how policies and procedures might be improved.

Some of the issues that our efforts focused on in 2009–10 were about the:

- accuracy and consistency of decision making about applications for pre-migration skills assessment

- advice given by contracted providers

- timeliness of decisions made under the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS).

Apprenticeships

During 2009–10 the Ombudsman's office investigated several complaints about the handling of claims made under the Australian Apprenticeship Incentives Program administered by DEEWR. Two main issues emerged from these complaints: quality of advice given by the Australian Apprenticeships Centre about claimants' eligibility; and consistency in decision making.

Consistency in decision making

The case study Australian Apprenticeship Support Services is an example of an investigation which considered the adequacy of DEEWR's guidance to staff to ensure consistency of decision making.

Australian Apprenticeship Support Services

Ms M took on an apprentice and expected to receive an incentive payment. When she found out that she did not qualify for the payment because of a change made to the guidelines while the apprentice was working for her, Ms M complained to this office. Our investigation found that DEEWR's decision to refuse Ms M's claim was not unreasonable. However, no consideration had been given to whether Ms Ms claim could be granted under the ‘exceptional circumstances' provision of the payment guidelines.

Discussion with DEEWR revealed that it did not have any examples or guidance regarding what might be considered exceptional circumstances. We queried DEEWR about the lack of information for claimants to decide whether or not to seek payment under exceptional circumstances. A lack of guidance also gives decision makers broad discretionary powers. DEEWR advised that it does not consider specific examples would be appropriate, but explained that staff considering claims of exceptional circumstances need to discuss these to ensure consistency of outcomes. Our office is currently considering whether to pursue this issue further.

Compensation for advice or actions of contracted providers

During 2009–10 our office received a number of complaints from people who believed they had been financially disadvantaged as a result of advice given or actions taken (or not taken) by providers contracted to deliver services on behalf of DEEWR. If the complainant had dealt directly with DEEWR on these matters, it would have been open to them to lodge a claim for compensation under the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme. However, they had no such avenue of redress when dealing with contracted providers.

Our office provided DEEWR with an issues paper on this topic in June 2010, suggesting that it consider implementing some CDDA-type means of compensating victims of defective administration under existing contracts and incorporating this process into new contracts.

In response DEEWR acknowledged that the suggestion raised in the issues paper was worthy of further consideration, however, the matter raised broader issues that should be canvassed at a whole-of-government level. DEEWR further noted that consideration might be given to revisiting the issue after the Senate Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee issues their report on government compensation payments.

Policy supporting sensible decisions—Trades Recognition Australia and the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Agreement

In 2009 the Ombudsman's office received a complaint about the interaction between two schemes for assessing skills for living and working in Australia. Our investigation, outlined in the case study TRA and the TTMRA, highlighted the incongruence of a licence that had been granted to a person on the basis of an international mutual recognition scheme not being considered suitable evidence to assess their job skills for permanent residency. This resulted in DEEWR agreeing to revisit its approach to these matters.

TRA and the TTMRA

Mr N was a New Zealand citizen living in Australia who was issued a licence to work as an electrician under the Trans-Tasman Mutual Recognition Agreement (TTMRA). Mr N decided to apply for permanent residency, and was required to undergo a skills assessment conducted by Trades Recognition Australia (TRA). Despite the fact that he was already living and working as a licensed electrician in Australia, TRA rejected Mr N's application on the basis that he had not sufficiently demonstrated his qualifications.

Our investigation revealed that under the Uniform Assessment Criteria (UAC) used by TRA to assess applications, a licence issued under the TTMRA was not considered suitable evidence of a qualification. We highlighted the lack of logic in this approach and, as a result, TRA has given an undertaking that it will revisit its treatment of licences issued under the TTMRA in the course of its review of the UAC.

Updates

Trades Recognition Australia

In our 2008–09 annual report we noted that we had received a large number of complaints from applicants wishing to obtain trade recognition for migration purposes. Applicants were unclear why their applications had been unsuccessful. In 2009–10 the number of complaints reduced significantly, though it is not yet clear whether this reduction is the result of improved decision making, recording and advice by TRA, or other factors, such as a recent change in TRA's assessment process. We also note that there is a cost to applicants in seeking a review.

The office will continue to monitor the adequacy of feedback that TRA provides to applicants prior to decision review.

Job seeker transfers

It is pleasing to note that the number of complaints regarding job seeker transfers has reduced significantly during 2009–10. While there could be a range of reasons for this reduction, it is worth noting that DEEWR implemented its new ‘Job Services Australia' (JSA) model of employment services from 1 July 2009. The JSA model replaced the previous Job Network and is promoted by DEEWR as giving job seekers and providers increased flexibility to access appropriate support and services.

Despite the reduction in complaints on this issue, it continues to be a significant source of complaints for our office and we will continue to monitor it in the coming year.

Cross-agency issues

Child care payments—Centrelink and DEEWR responsibility

In previous annual reports we have discussed the complexities of investigating complaints that involve more than one agency. In 2009–10 we received a number of complaints about the Child Care Management System (CCMS), which is used by the Government to exchange information with child care providers about customer usage and entitlements. While Centrelink delivers the payments to assist families with the cost of child care, DEEWR has responsibility for managing the CCMS and relationships with child care providers. This has led to customers experiencing confusion and difficulty in understanding which agency is responsible for resolving errors in the assessment of child care entitlements. The following case study, Centrelink or DEEWR CCMS? illustrates just such an example.

Looking forward

In March 2010 DEEWR implemented a new model of delivering employment services to people with a disability, called Disability Employment Services. This model replaces a number of different ways that these services were previously delivered, and combines them into two distinct streams of support.

Given the short time frame in which the new model has been in place, we have not yet had an opportunity to fully assess how the new model is working for jobseekers. We will monitor this area for complaints during 2010–11.

Centrelink or DEEWR CCMS?

Ms O complained that she had not received her quarterly child care tax rebate (CCTR) payment despite contacting Centrelink more than 15 times. She advised that, at the request of Centrelink, her child care provider had resubmitted its attendance data three times and still no payment had been forthcoming.

We contacted Centrelink and DEEWR and were advised that, in order for the problem to be rectified, Ms O's child care provider would have to retract all previous attendance data and resubmit the data. This information had not previously been provided to Ms O because she had been dealing with Centrelink and not with DEEWR, who oversees the CCMS.

We contacted Centrelink and DEEWR to draw their attention to the problems faced by families when trying to understand why their CCTR had not been paid, and recommended that a suitable complaint process be implemented. DEEWR and Centrelink subsequently advised that there was a process in place through Centrelink with escalation points to the CCMS. The agencies advised that, following our investigation, they had met to review the complaint process and explore further improvements.

Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency

During 2009–10, we received 341 complaints about the Department of Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts (DEWHA), and 153 complaints about the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency (DCCEE).

In contrast, in 2008–09 we received only 46 complaints about DEWHA and six complaints about the Department of Climate Change. In 2009–10 we formally investigated 64 complaints about DEWHA and 69 complaints about DCCEE.

Most complaints received during 2009–10 concerned the Australian Government's energy efficiency and renewable energy programs, particularly the solar panel rebate under the Solar Homes and Communities Plan, the solar hot water rebate under the Energy Efficient Homes Package, the Home Insulation Program, and the Green Loans program.

On 8 March 2010, DEWHA's energy efficiency and renewable energy functions were transferred to the Department of Climate Change, which became the Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency.

Complaint handling

Many of the complaints we received raised concerns about DEWHA's failure to respond adequately to enquiries and complaints lodged directly with that department. In light of this, in September 2009 we commenced an own motion investigation into DEWHA's complaint-handling policies and processes.

In its response to this investigation, DEWHA acknowledged that enquiries and complaints to the department had increased in parallel with the expansion in its energy efficiency programs, and that its complaint-handling arrangements were no longer adequate given its changed circumstances. It advised that it was in the process of revising its complaint-handling policies and procedures, with reference to the Ombudsman's Better practice guide to complaint handling.

In early 2010, staff from the Ombudsman's office and DEWHA met via teleconference to discuss the department's enquiries and complaints processes, particularly in relation to the Green Loans program.

After the transfer of DEWHA's energy efficiency programs to DCCEE in March 2010, we decided to finalise our investigation without publishing a report, given that DEWHA was already in the process of bringing its complaints policies and procedures into line with our Better practice guide to complaint handling . We will continue to work with DEWHA as it goes through this process.

We also worked closely with DCCEE as it established new complaint-handling processes after responsibility for the energy efficiency program was transferred to it. Once again, we will continue to work with the department as it implements a centralised complaint-handling system that reflects our better practice guide.

Delay in processing

Mr P applied for a solar panel rebate in early 2009. The claim form indicated that processing would take six weeks. Five months later Mr P complained to our office that his application had not been finalised, and that DEWHA had not explained the delay, despite him making several phone calls to the department and writing to the Minister. The department explained to us that the delay was caused in part by Mr P's application having been incomplete. The department had sought the missing information from the installer, who had taken two months to provide it. However, the department acknowledged that it had not responded appropriately to Mr P's complaints. It had not explained to him that his application was incomplete, nor that it had sought the information from the installer.

No complaint process

Ms Q applied for a solar hot water rebate in May 2009. Several weeks later she contacted DEWHA to confirm that it had received her application. She was told that that information was not available, and to call back in four weeks. Four weeks later, Ms Qcalled the department and was told that the department still could not confirm that it had received her application because of delays in processing applications. Ms Q complained to our office that when she then asked to speak to a supervisor to lodge a complaint, she was told that there was no process available to do so. Subsequently Ms Q's application was approved, but there was a delay by the department in depositing the funds into her bank account. Ms Q then lodged an online complaint with the department, and made further phone calls, but the department did not respond to her complaint. The recorded reason was: ‘Due to the tone of her calls I have not attempted to respond or provide further explanation to her complaints (misinformation, poor service, incompetence etc.)'.

Solar panel rebates

On 8 June 2009, the Minister for the Environment announced that the Australian Government would only accept completed applications for the popular $8,000 solar panel rebate that were sent to DEWHA before midnight on 9 June 2009.

We subsequently received many complaints about DEWHA's rejection of applications because they were received late or were incomplete. We carefully considered the reasonableness of the department's criteria for determining whether an application had been sent before the 9 June 2009 cut-off, the reasonableness of its criteria for deciding whether an application was substantially complete or not, and how the department applied these criteria in particular cases.

In many cases, we were able to satisfy the complainants that the department's criteria were reasonable, and had been properly applied in their cases. In other cases, the department agreed to reconsider the applications as a result of our investigation.

We also received complaints about solar panel applications having been lost. The department confirmed that more than 1,000 applications may have been lost. Most of these were claimed to have been sent in bulk by installers before the 9 June cut-off. It was unlikely that an investigation by this office would be able to determine whether any particular applications had in fact been lost, and whether the loss had occurred in transit or after they had been received by the department.

In light of this, we again focused on the reasonableness of the criteria used to determine whether to accept resubmitted applications. DEWHA and DCCEE proactively engaged with us in designing the process for considering resubmitted applications. We ensured that the criteria were clearly communicated to the installers who had complained to our office, as well as to their individual customers.

Group application

Fifty permanent residents of a caravan park formed a group to apply for solar panel rebates through a single installer. The installer claimed to have submitted all 50 applications prior to the 9 June 2009 deadline. DEWHA accepted 43 applications, but rejected seven for lateness and/or incompleteness. Upon review, one application was accepted but the rejection of the other six was upheld. However, after investigation by our office, the department (now DCCEE) conducted a second review and granted approval for the remaining six applications.

Two out of three

Mr R complained that an installer had submitted three applications for the solar panel rebate for himself and two other members of his family. The other two applications had been approved, but his had been rejected as incomplete. Our investigation confirmed that, in Mr R's case, the installer had neglected to include the part of the application in which the installer certified that the proposed system would comply with the relevant standards and legislative requirements, meet the rebate guidelines, and was appropriate for Mr R's location. We considered that it was not unreasonable for DCCEE to have assessed the application as materially incomplete.

Lost applications

Mr S has a business installing solar panels, and complained that he had sent in more than 3,000 solar panel rebate applications before the 9 June 2009 cut-off, but DEWHA had no record of receiving 618 of these. Mr S had met with the department in October 2009, and had followed up but had not received clear advice about the missing applications.

Mr S also complained that the department had paid the rebate to three of his customers whose applications had been lost, after they had submitted duplicate applications together with statutory declarations stating that their original applications were posted by 9 June 2009. However, DEWHA had not adopted this for other missing applications.

In response to our inquiries, DEWHA advised that it had approved Mr S's three customers' applications in error. It again met with Mr S and advised him that it was still finalising its policy on lost applications. Mr S also contacted us after the meeting and expressed concerns about the department's request that he provide copies of the original applications. He explained that very few of his customers had kept copies.

We discussed the situation with DEWHA and also DCCEE (after responsibility for the program was transferred to it in March 2010). We emphasised the need for a timely resolution to the problem, given the large number of people who were affected.

Ultimately, in May 2010 DCCEE wrote to all applicants whose applications were missing, inviting them to resubmit their applications, together with supporting evidence to show that they had applied before the 9 June 2009 cut-off. Where applicants had not kept a copy of their original application, they were offered the opportunity to submit a duplicate application together with a statutory declaration to that effect.

In our view, this policy for dealing with lost applications seemed reasonable.

Home Insulation Program

We received more than 60 complaints concerning DEWHA/DCCEE's administration of the Australian Home Insulation program. Most of these complaints were from householders who were concerned about delays in rebate applications being approved, or from installers about approved rebates being paid.

Some householders were concerned about the quality and safety of the insulation that had been installed in their homes, and whether the department was taking steps to regulate installers and check the quality and safety of the insulation materials used.

Householders also complained about fraudulent claims for the rebate in relation to their properties. In some cases, the possibility of a fraudulent claim came to the householder's attention when their rebate application was rejected because a rebate had already been paid for their property. In other cases, the householder received a letter from the department confirming that a rebate had been paid to an installer for their property, when the householder had not in fact made an application. In these cases, we advised the complainant to draw the department's attention to the issue so that it could take compliance action.

Green Loans program

We received 126 complaints about the Green Loans program from Green Loans assessors concerned about difficulties in obtaining assessment bookings, or about delays in the processing of invoices and difficulties in communicating with the departments generally.

Green Loans assessors

We received complaints from Green Loans home sustainability assessors about the DCCEE's delayed payment of their invoices. In some cases, the complainants had contacted the department numerous times to enquire about the status of their payments. Although they had used the dedicated email address and phone number advertised by the department, they had not received any response. DCCEE advised our office that the same team processing the payments was also required to deal with complaints and enquiries. As payment processing was considered a priority, the department was not able to respond to complaints or enquiries in a timely manner. At our suggestion, DCCEE improved the information it provided to assessors about payment time frames by posting regular payment processing updates on its website, and amending its auto-reply email message to inform complainants to expect delays and to advise which invoices the department was currently processing.

Systemic issues

Many of the complaints to our office echoed media concerns about the energy efficiency programs. The Australian Government has responded to some issues by making changes to administration, or by commissioning an inquiry into the relevant aspect of the program.

We declined to investigate complaints where the departments were already taking steps to remedy problems, and where our investigation would have duplicated another inquiry. However, even in these cases we liaised regularly with the departments to ensure that they were aware of the full range of issues and concerns that complainants were raising with us, and to ensure that steps were being taken to address the problems. We also regularly sought improvements to their complaint-handling processes and the way in which information was provided to the public.

Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs

Indigenous programs in the Northern Territory

The office has been funded until 2011–12 to provide independent oversight of the Northern Territory Emergency Response (NTER) and the Closing the Gap NT initiatives.

Apart from oversighting the NTER and the Closing the Gap NT initiatives, the Indigenous Unit of the Commonwealth Ombudsman also monitors all Australian Government programs that have an impact on Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory (NT).

Complaints received from Indigenous Australians in the NT primarily relate to the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA), the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations (DEEWR) and Centrelink. This is to be expected as they are large and complex government agencies responsible for programs that have an impact on people's everyday lives. The Ombudsman also works with other agencies as the need arises.

Complaint themes

The Ombudsman's office dealt with 322 complaints relating to the NTER or Indigenous programs in the NT. Almost all of these complaints were received during outreach to 39 communities and town camps.

In considering these statistics the following should be noted:

- the number of complaints received is directly related to the number of outreach visits conducted because few complaints are received from Indigenous people through the office's usual avenues (telephone, letter and internet)

- the Ombudsman's office's outreach program is scheduled to ensure adequate time is available for investigations to be completed, and issues to be pursued

- it is clear from our outreach visits that there are many more complaints than this office is presently resourced to handle.

The issue which attracts the highest number of complaints is housing. Problems arise from complex leasing arrangements, the Strategic Indigenous Housing and Infrastructure Program (SIHIP), the devolution of housing repair and maintenance services to local shires, as well as the delivery of municipal and essential services to communities. Such complaints are recorded against FaHCSIA; however, they often also concern the NT Department of Housing, Local Government and Regional Services (DHLGRS), for example:

- housing repairs and maintenance

- rent

- tenancy agreements

- housing allocation decisions

- housing reference groups

- municipal and central services—such as mowing, fencing, repairs to and usage of public buildings.

The case studies on the following page highlight the diversity of concerns.

Other major issues of complaint relate to Income Management, the School Nutrition Program, Job Services Australia providers and land council decisions. Businesses and individuals also complain about the BasicsCard scheme.

House maintenance

Ms T complained about the condition of her house, saying that the stove did not work and that no repairs or maintenance had been undertaken in her community for some time. This was an issue for many people in the community.

Our investigation revealed some confusion about who was responsible for the repairs. While FaHCSIA was the landlord, responsibility for tenancy management and repairs had been devolved to the NT DHLGRS. DHLGRS had provided funding to the local shire for repairs and maintenance, but the shire was not clear on whether stoves were included in those things they were required to maintain.

As a result of this complaint and our investigation, the shire arranged for Ms T's stove to be replaced, along with 19 others in her community.

Community access to playgrounds

Residents of a remote community complained that there was no play equipment for the children outside of school hours as the school gates were locked at the end of the school day. We were told that new play equipment had been ordered for two other communities in the area, but not for this community. While we were in the community we saw metal grids placed in the area where the community said they would like a playground located.

When we investigated, we were advised that the Shire Council had not ordered play equipment for this community because there was play equipment at the school. Following our investigation, the Shire Council ordered new play equipment and the agency will fund the erection of shade cloth over the play area.

BasicsCard usability

Mr U owned a roadhouse and had applied to Centrelink to be approved as a BasicsCard merchant for fuel, power and groceries. Centrelink had approved Mr U to be a BasicsCard merchant for fuel and power, but not for groceries because the policy, which was developed by FaHCSIA, did not allow roadhouses to sell groceries through BasicsCards. Mr U had requested a review of the decision, but did not receive a response.

Following an Ombudsman investigation of this complaint, Centrelink reviewed its decision and decided to approve Mr U's roadhouse for the full range of BasicsCard purchases, including groceries. We recommended that Centrelink review its decision letters to merchants so that it explained the merchant's review rights. Centrelink accepted our recommendation and amended its template letters. The complaint investigation also prompted a review of the roadhouse policy.

Complaint themes and cross-agency issues

It is evident that most agencies have not established accessible complaint mechanisms of their own in remote communities. Consequently, many issues that could be resolved by agencies do not come to their attention until we raise the complaint with them.

The need for improved communication was the subject of a public report that we released in late 2009 arising from complaints about asbestos management in remote communities.

A recurring theme throughout complaints is a concern about poor communication or a lack of information provided to Indigenous people about government programs affecting them. This is particularly acute where program decisions are made but not adequately conveyed or explained. Passive delivery of information, and information which is inappropriately targeted, misleading, unclear, untimely, inaccessible or simply non-existent lies at the heart of a significant number of complaints investigated by the Ombudsman, either as a primary issue or related factor.

This often involves a failure to engage, or interpreters not being available (which is the subject of a separate public report under consideration by this office).

This issue is seemingly at odds with the observation made by a number of community organisations that Aboriginal communities feel they have been ‘over-consulted'. Perhaps it is the same few prominent community leaders who have been consulted many times on issues of lower importance, and on broader more important issues, consultation with communities has not been well targeted. An ongoing issue reported to this office is the failure of clear follow-through or reporting back on consultations.

Poor communication is often compounded by the increasing trend towards service delivery involving two and often three tiers of government. While multijurisdictional service delivery can present complex problems for agencies, there is an increased risk of people being passed from one level of government to another without their concerns or needs being addressed.

The Ombudsman's role is particularly complex in this area because so many programs for Indigenous Australians are cross-agency or multijurisdictional. Additional issues arise because of the way Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreements define or describe Australian Government responsibility for outcomes.

Programs and services may also be delivered through memorandums of understanding (MOU) and service level agreements between the Australian and NT Governments or through more direct funding to states and territories. We generally assert Commonwealth jurisdiction on the basis that the Commonwealth, primarily via FaHCSIA, is accountable for the delivery of outcomes under these high-level agreements.

Reports

The Commonwealth Ombudsman is currently drafting a report about agency access to Indigenous language interpreters.

We are also finalising a report under s 15 of the Ombudsman Act that arose from an investigation into a specific complaint concerning the administration of Performance Funding Agreements for service providers based in remote Indigenous communities. Another report we are currently finalising relates to the review rights of income-managed people in the NT.

Engagement

In addition to complaint investigations, the Ombudsman's office conducts regular formal liaison meetings with the key agencies involved in Closing the Gap NT programs. The aim is to gain early feedback about various government programs and to provide an opportunity for agencies to adjust and refine their programs and processes before more people are adversely affected.

This strategy has the potential to address a problem before it affects more clients and attracts wider attention and criticism. The Ombudsman is in a strong position to contribute to the improved delivery of government programs and if these cooperative objectives are understood, improved outcomes should follow.

The Ombudsman's office deals predominantly with FaHCSIA, Centrelink and DEEWR and attends regular liaison meetings in Darwin and Canberra. During 2009–10, we attended agency liaison meetings with other agencies that run programs for Indigenous people and remote communities in the NT, including:

- the Attorney-General's Department

- Department of Broadband, Communications and the Digital Economy

- Department of the Environment, Water and Heritage

- Department of Health and Ageing.

During the year, we also met regularly with:

- the Indigenous Policy Branch of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet in an effort to advance whole-of-government issues and receive updates from inter-agency forums of which we are not members

- the Coordinator-General for Remote Indigenous Services to share information and discuss relevant issues and approaches

- Territory Housing—a joint Australian and NT Government office in Darwin.

Outreach

The Commonwealth Ombudsman is the primary avenue of independent oversight of many Australian Government Indigenous programs. As a result, visits to Indigenous communities in the NT form a very important component of our outreach program.

An MOU with the NT Ombudsman signed in December 2009 facilitates a single interface for people who wish to complain about cross-jurisdictional issues in the NT.

The frequency of outreach visits and the time taken to investigate complaints can be significantly lengthened due to agency response times. We recognise the challenges that a large government agency such as FaHCSIA has in responding to our questions, which will often relate to a complex and multijurisdictional environment. We are currently refining our approach to complaints that involve cross-agency issues in consultation with FaHCSIA and relevant NT Government agencies.

Community organisations

We continue to examine how we can best engage with community agencies and organisations in the NT. These organisations are an important source of information about issues of concern and they also have the capacity to refer their clients to our services.

In 2009–10 we continued to share promotional and educational activities with other organisations. For example, together with the NT Ombudsman we made a presentation to the Batchelor Institute.

Other activities included information presentations about Ombudsman services to community board meetings and other community organisations such as the Central Australian Youth Link-Up Service (facilitating internet access at Papunya).

Looking ahead

Many complaints arise from the experience of one individual who is lost in the enormity of government programs. People need to know where to get information about government programs that affect them.

After more than three years of the NTER and Closing the Gap NT, communication challenges in remote NT remain a significant issue, and are the underlying cause of many complaints.

These challenges are shared by the office in its own communication with Aboriginal people and communities in the NT and nationally. The office is committed to improving its engagement to make its own services more widely accessible.

A project officer was engaged to develop an Indigenous communication and engagement

strategy in 2010. A key part of this project is formal evidence based research in order to shed light on how we can communicate better. We want to find out what messages Indigenous people respond to and why. We want to target our messages better and use the most appropriate tools. This research will be completed in the second half of 2010. It will assist the office to:

- be accessible to more Indigenous Australians

- use best practice communication with Indigenous Australians

- engage more closely with community and other stakeholders by sharing this information.

In other policy areas, decision-making tools can get in the way of good decisions at the expense of policy outcomes. The case study Helping Children with Autism Scheme illustrates this issue.

Helping Children with Autism Scheme

Ms V was granted assistance under the Helping Children with Autism (HCWA) scheme, which aims to support early intervention for under-school-age autistic children. Ms V complained to us that FaHCSIA had refused her claim for the Outer Regional and Remote Payment (ORRP), which provides additional assistance for HCWA recipients, because her address was not considered ‘outer regional and remote' (under the Accessibility Remoteness Index of Australia (ARIA+) tool used to assess ORRP claims). Ms V complained that she would not be able to use the HCWA funding she had been granted because she could not afford to travel to access these services.

We advised FaHCSIA of our view that while a grantee may live near a ‘service centre' as classified by ARIA+, it does not necessarily follow that there is a FaHCSIA approved provider in the vicinity of that service centre. We suggested that FaHCSIA consider using an alternative method of assessment. In response, FaHCSIA agreed to implement a special consideration for assessing ORRP applications. Under the changes, Ms V was granted the ORRP for her family. In addition, as a result of this enquiry other internal review processes were implemented to assist families seeking assistance.

Fair Work Ombudsman

The Office of the Fair Work Ombudsman (Fair Work Ombudsman) was established on 1 July 2009 to promote harmonious, productive and cooperative workplace relations, and to monitor, enquire into, investigate, and enforce compliance with relevant Commonwealth workplace laws. Its predecessor, the Office of the Workplace Ombudsman, had similar functions, although the Fair Work Ombudsman has a greater educational role.

In 2009–10 we received 57 complaints about the Fair Work Ombudsman, compared to 65 complaints about its predecessor the year before. The main issue centred on the conduct of investigations.

During 2009–10 we undertook an own motion investigation ( Fair Work Ombudsman: Exercise of coercive information-gathering powers , report no. 09|2010) focusing on the policies and guidelines used by the Fair Work Ombudsman when exercising its powers during investigations. We used the principles contained in the Administrative Review Council's (ARC) The Coercive Information-Gathering Powers of Government Agencies (report no. 4, May 2008) as a guide.

Overall, we found that the Fair Work Ombudsman is acting consistently with the principles contained in the ARC report. We were impressed with the quality of the procedures in place to manage the coercive information-gathering powers used by its inspectors. The own motion report included some recommendations for further procedural improvement, which were positively received by the Fair Work Ombudsman.

Department of Health and Ageing

The Ombudsman finalised 151 approaches and complaints about the Department of Health and Ageing (DoHA) in 2009–10, of which 57 were investigated.

The main themes arising from complaints were:

- the quality of DoHA investigations into aged care complaints

- the currency, accuracy and appropriateness of communications with the public (including material made available to the public on DoHA's websites)

- access to DoHA services in remote communities.

Complaint themes

The most common type of complaints received about DoHA concerned its Aged Care Complaints Investigation Scheme (CIS) and its decisions on recommendations made by the Aged Care Commissioner (ACCr).

In September 2009, the Ombudsman made a submission (based on complaints received) to DoHA's Review of the Aged Care Complaints Investigation Scheme conducted by Associate Professor Merrilyn Walton.

Respecting the dignity of care recipients

The complainant's father and another resident had raised some concerns during a general meeting of the care facility. They felt that the manager was rude to them in response. The complainant said that the following day the manager had spoken to each of them separately in their rooms and they felt that this was bullying in response to the incident at the meeting. The manager said she spoke ‘sternly' to the residents but had not treated them with disrespect.

The CIS decided that there had been a breach of the requirement to respect the dignity of care recipients, but that this had been rectified and no further action was required. Both the facility and a resident's family appealed to the ACC. The facility argued that there had been no breach of the requirements and the resident's family argued that there should be further action taken. The ACC decided that there was insufficient objective evidence of the conversations to establish that a breach had occurred.

In this case the complaint process met regulatory needs, but placed the parties in an adversarial position. The process did not address the perceptions of the parties, which were likely to continue to affect their ongoing relationship. Addressing these matters is important to the way residents feel in a care facility that is essentially their home.

Our concerns about the complaints investigation scheme include:

- the time frame of 14 days for a person to appeal to the ACC against a decision of the CIS is too short. Complainants in the aged care context may need to talk about their complaint with family members before proceeding and most similar administrative appeals processes allow at least 28 days

- the scheme does not cover government funded aged care services outside the Aged Care Act 1997 , such as flexible programs providing services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities

- the scheme is directed towards regulatory rather than complaint resolution outcomes, often leaving a complainant's dispute unresolved or without redress

- the scheme does not always offer sufficient opportunity to comment before a decision or a recommendation is made

- in some cases the reasons for decisions of the department's delegate to accept or reject the ACC's recommendations are not sufficiently transparent.

In particular, the current complaints scheme has not provided the type of resolution mechanism required in circumstances where there will be an ongoing relationship between a care facility and care recipient.

The case Explaining decisions how a complaint can remain unresolved due to inadequate explanation to the complainant of the reasons for a decision.

Explaining decisions

Mr W's care facility decided that it could no longer care for him due to his increasing needs and that he would be better placed elsewhere. The User Rights Principles (the Principles) provide for certain processes to be followed where a residence either asks or requires a care recipient to leave in these circumstances. In this case the care facility said it did not follow the process under the Principles because Mr V left the facility voluntarily.

On Mr W's behalf, the complainant complained to the CIS and to the ACC that Mr W had not left voluntarily, but rather was told he would have to leave.