Annual Report 2010-11 | Chapter 6

Chapter 6

Helping people, improving government

A large part of our work is resolving individual complaints and, through this process, improving public administration. This chapter outlines our work in obtaining remedies for individuals, and improving public administration in areas such as communication, procedures and better complaint handling.

The chapter concludes with a brief explanation of the role of identifying administrative deficiency in agency operations.

Remedies

When investigating an individual complaint, it is important to seek out a remedy for the complainant. Remedies might include an apology, giving better reasons for a decision, expediting action or finding a financial solution.

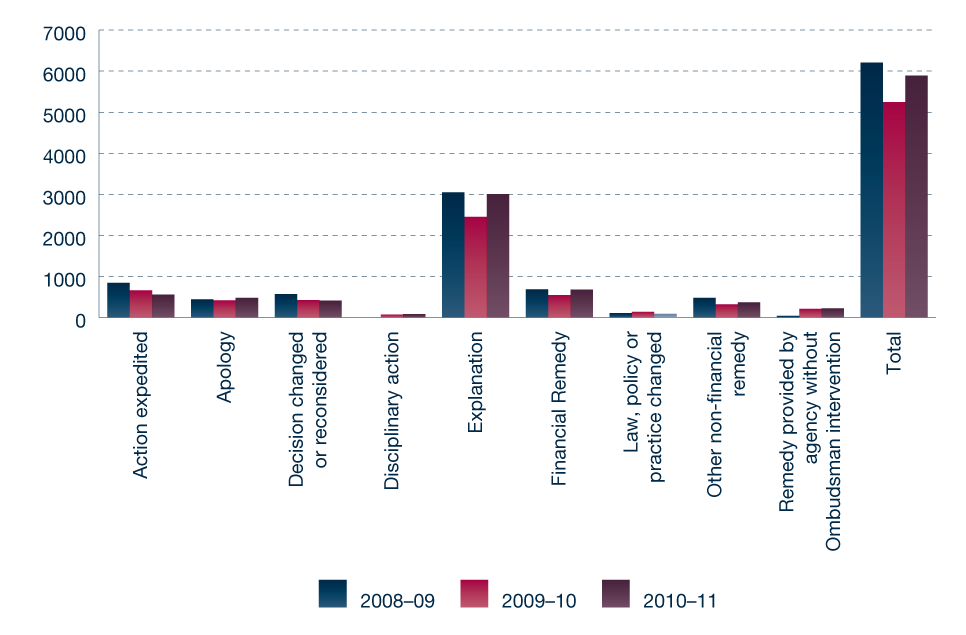

Figure 6.1 shows the range and number of remedies achieved by the office for complainants. For the year 2010–11 there were 5,890 remedies, up from 5,245 in the year 2009–10 (an 11% increase).

Figure 6.1: Remedies achieved for complainants 2008–09 to 2010–11

For information on possible remedies that are available to Australian Government agencies refer to

Fact sheet 3—Remedies

, on our website

(www.ombudsman.gov.au).

This section gives a brief explanation of some of the remedies we obtained for individuals through our complaint investigations in 2010–11.

Explanations

Providing a clear explanation of a decision is an important remedy. It can reduce a person’s concerns, even if the decision cannot be altered. Giving the reasons for a decision can also be of practical assistance. For example, it may help the person to decide whether to make a fresh application, or seek review or reconsideration of the decision.

Actions and decisions

We receive many complaints about agency decisions. A frequent complaint is that there is delay by an agency in making a decision. Often, a suitable remedy in this situation is to expedite action. Another frequent complaint is that an agency has made a wrong decision. We respect the right of agencies to decide the merits of a claim, but we do examine whether an agency has made a decision based on wrong or incomplete information, ignored relevant information or not applied the principles of natural justice. The appropriate remedy in these circumstances may be for the agency to reconsider or change a decision.

Financial remedies

Poor administration can cause financial loss to people. For example, a person may not receive a benefit to which they were entitled, their benefit may be reduced below their real entitlement, they may have a debt raised against them unreasonably, or they may suffer other financial losses. There is a range of remedies that can be used to provide financial relief or compensation to a person. One remedy is that compensation may be payable under the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) scheme. In other cases, a debt may be waived or reduced. Other financial remedies might include a refund of fees or charges, or payment of a particular benefit.

Apologies

An apology can be highly effective in addressing a person’s complaint. As a matter of general courtesy and good public administration, an agency should apologise and provide an explanation to a person when an error has occurred. Complainants often see an apology as the first step in moving forward.

Good administration

An individual complaint can highlight a recurring problem in agency administration. Following an investigation, the Ombudsman’s office may recommend broader changes, such as better training of agency staff, a change to agency procedures or policies, a revision of agency publications or public advice, or a review of government policy or legislation that is having harsh or unintended consequences.

These recommendations may be pursued in various ways. We may raise the issues with an agency through regular liaison, propose improvements during an investigation, or make a recommendation in a formal report.

During 2010–11 the office published 13 formal reports, comprising some 80 recommendations—90% were accepted in full and 9% in part. Some of these dealt with an individual complaint investigation, some arose from the investigation of numerous similar complaints, and others were own motion investigations dealing with systemic issues. Reports released were:

- Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs and Centrelink: Review rights for Income managed people in the Northern Territory (Report 10|2010)

- Child Support Agency, Department of Human Services: Investigation of a parent’s ‘capacity to pay’ (Report 11|2010)

- Australian Taxation Office: Resolving Tax File Number compromise (Report 12|2010)

- Falling through the cracks—Centrelink, DEEWR and FaHSCIA: Engaging with customers with a mental illness in the social security system (Report 13|2010)

- Department of Human Services, Child Support Agency: Unreasonable Customer Conduct and ‘Write Only’ policy (Report 14|2010)

- Australian Customs and Border Protection Service: Administration of coercive powers in passenger processing (Report 15|2010)

- Administration of funding agreements with regional and remote indigenous organisations (Report 16|2010)

- DAFF Biosecurity Services Group: Compliance and investigations activities of the Biosecurity Services Group (Report 01|2011)

- Christmas Island immigration detention facilities (Report 02|2011)

- DIAC: Proper processing for challenging a tribunal decision (Report 03|2011)

- Centrelink: Right to review—having choices, making choices (Report 04|2011)

- Talking in Language: Indigenous language interpreters and government communication (Report 05|2011)

- DEEWR: Administration of the National School Chaplaincy Program (Report 06|2011).

Improving communication and advice to the public

People rely on government agencies for advice and information about the legislation and programs administered by government. They expect this advice to be accurate and practical. Any qualification or limitation on the general advice provided by an agency should be explained, and if appropriate, a person should be cautioned to seek independent advice relevant to their individual circumstances.

For example, our report entitled DEEWR: Administration of the National School Chaplaincy Program (Report 06|2011) made clear recommendations to the Department about improving engagement and consultation with the community, in particular school communities impacted by the roll-out of the program.

Having good procedures

Government agencies must have sound procedures in place to administer complex legislation and programs in a manner that is efficient, effective, fair, transparent and accountable. Many complaints to the Ombudsman’s office arise from poor agency procedures.

Many of the reports we published during the year contained recommendations aimed at improving agency procedures.

The report Department of Human Services, Child Support Agency: Unreasonable Customer Conduct and ‘Write-only’ policy (Report 14|2010) highlighted the need for clear and sound procedures for engaging with the public, particularly when managing unreasonable customer conduct.

Interpreting and applying legislation and guidelines correctly

The public relies on government agencies to act lawfully and make lawful decisions. An agency should always be aware of the danger of staff not correctly interpreting legislation or agency guidelines. To deal with this risk, agencies need to have adequate internal quality controls, look for inconsistencies in the application of legislation or guidelines, and focus on problem cases.

The importance of consistent and correct application of legislation and guidelines was highlighted in the report FaHCSIA and Centrelink: Review rights for income managed people in the Northern Territory (Report 10|2010).

Good complaint handling

Good complaint handling is a central theme of Ombudsman work. A good complaint-handling process provides a way for problems to be dealt with quickly and effectively. It can also provide an agency with early information about systemic problem areas in administration. Poor complaint handling can exacerbate what may have been a simple error or oversight, potentially giving rise to other complaints from the person concerned and to a loss of public confidence in the agency.

Over the years the Ombudsman’s office has put considerable effort into helping agencies improve their complaint-handling processes. We have done this in a variety of ways, including liaison and training, reviews of agency complaint-handling systems, and publishing relevant material.

The Ombudsman publication Better Practice Guide to Complaint Handling defines the essential principles for effective complaint handling. It can be used by agencies when developing a complaint-handling system or when evaluating or monitoring an existing system.

Many of the investigation reports published during 2010–11 contained recommendations relating to how complaints can be handled better. For example, our report entitled Centrelink: Right to review–having choices, making choices (Report 04|11) highlighted the need for more transparent processes for options of review and handling of complaints.

We found that navigating between government agencies to fix a problem can be extremely difficult for customers, and that agencies that work together to deliver programs must also work together to resolve problems arising from those programs. This was particularly relevant to the circumstances of people with mental illness, seeking to communicate and resolve complaints with government agencies, as highlighted in the report Centrelink, DEEWR and FaHCSIA—Falling through the cracks: Engaging with customers with a mental illness in the social security system (Report 13|2010).

Record keeping

Many complaints relate to poor record keeping from agencies. A delayed decision will often compound a problem. Poor record keeping can also undermine transparency in agency decision making and lead to allegations of deception, bias, incompetence or corruption.

Sometimes simple errors such as misplacing or losing a file, failing to keep a proper record of an important decision or conversation, or inadvertently confusing people who have similar or identical names, can lead to substantial problems for a person.

Given that the consequences of compromises are often dire, keeping accurate records and protecting the information of customers must be crucial priorities for government agencies, as highlighted in the report Australian Taxation Office: Resolving Tax File Number compromise (Report 12|2010).

Administrative deficiency

Section 15 of the Ombudsman Act lists the grounds on which the Ombudsman can formally make a report to an agency, and ultimately to the Prime Minister and the Parliament. A small number of such reports are made each year to agencies, but reports to the Prime Minister or the Parliament are rare. Most complaints to the Ombudsman can be resolved informally, and without the need to reach a firm view on whether an agency’s conduct was defective. This reflects the emphasis of our work on achieving remedies for complainants, and on improving agency complaint-handling processes and public administration generally.

Nevertheless cases do arise in which administrative deficiency should be recorded. This helps to draw attention to problems in agency decision making and processes, and feeds into the office’s work on identifying systemic issues. The purpose of a finding of administrative deficiency is not to reprimand the agency concerned, and the individual findings are not separately published in the same way that reports under s 15 are usually published. The emphasis is on finding solutions and improving administration.

During 2010–11 we recorded 281 cases where there was administrative deficiency by a government agency (a drop from 340 cases in the previous year).