Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2012—13 | Section 4

Section 4 Agencies Overview

Most of the approaches and complaints we received about Australian Government agencies in our jurisdiction (76%), related to the following five agencies (or programs within the agencies):

- Centrelink (Department of Human Services) – 5,093 complaints (28% of the total we received)

- Australia Post – 3,652 (20%)

- Australian Taxation Office – 1,795 (10%)

- Child Support (Department of Human Services) – 1,736 (10%)

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship – 1,547 (8%).

This chapter discusses our work with four of these agencies, or programs, in handling complaints and dealing with broader issues during this financial year. Our work with Australia Post is detailed in the overview of the Postal Industry Ombudsman in Chapter 7.

Chapter 7 will provide an overview of the specialist roles we perform, including the:

- Defence Force Ombudsman

- Immigration Ombudsman

- Overseas Students Ombudsman

- Postal Industry Ombudsman

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- Inspection functions.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (DHS) delivers the Australian Government’s Centrelink, Child Support and Medicare programs. DHS is also responsible for delivering a number of smaller programs, such as CRS Australia, Australian Hearing, the Small Business Superannuation Clearing House, and the Early Release of Superannuation Benefits on Specified Compassionate Grounds program.

The Ombudsman received a total of 7,192 complaints about DHS programs in 2012–13 (a reduction of almost 25% from 2011–12, when we received 8,967). Complaints about the Centrelink program accounted for almost 71% of the complaints about DHS, followed by Child Support (just over 24%). The bulk of the remaining DHS complaints were about Medicare and the Early Release of Superannuation Program.

Centrelink

Centrelink delivers social security and family payments, plus a range of other payments and services to people in the Australian community, and some people overseas. On 1 July 2012 Centrelink was integrated into DHS and ceased to be a discrete Australian Government agency. However, we have continued to separately record the complaints we received about DHS’ Centrelink program (Centrelink) to allow us to compare complaint trends over the years.

Complaint themes

In 2012–13 we received a total of 5,093 complaints about Centrelink. Although this is fewer than in 2011–12, when we received 6,355, it still represents the highest number of complaints recorded about any Australian Government agency or program in 2012–13. In fact, Centrelink, and its predecessor, the Department of Social Security, has consistently received more complaints than any other agency or program every year since 1994. However, we must acknowledge that the large numbers of complaints about Centrelink are explained, in part, by the nature of the services that Centrelink delivers (such as means tested income support payments) and the sheer scale of its operations.

Centrelink processes a high volume of administrative transactions each year, for example in 2011–12 it had more than 7 million customers, answered more than 44 million telephone calls, sent out more than 100 million letters, and sent a further 19 million items of online correspondence. However, we do observe changes in the pattern of complaints about Centrelink, and this year was no exception. In this section we make some observations about Centrelink’s administration (based on the volume of calls to our office), the issues that people identify in their complaints, and what we learned from the complaints that we investigated.

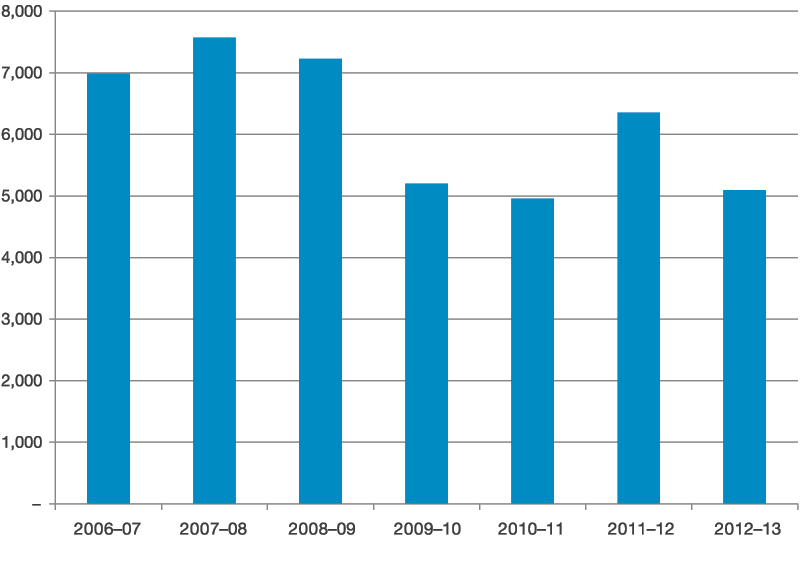

Figure 4.1: Number of complaints and approaches about Centrelink from 2006–07 to 2012–13

This chart shows the number of complaints and approaches about the Centrelink made to our office from 2006–07 to 2012–13. These are: 6,987 in 2006–07; 7,573 in 2007–08; 7,226 in 2008–09; 5,199 in 2009–10; 4,954 in 2010–11; 6,355 in 2011–12 and 5,093 in 2012–13.

Access to Centrelink’s internal complaint service

In last year’s annual report we noted that Centrelink complaint numbers had increased, following two years when they decreased. We attributed this to two main factors: firstly, there were large numbers of complaints about significant wait times on Centrelink’s telephone lines; and secondly, Centrelink customers were bypassing Centrelink’s complaint service to express their dissatisfaction and calling the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office instead. We believed this change in customer behaviour was driven by Centrelink’s decision in early 2012 to remove the telephone number of its complaint service from its letters. Instead, its letters referred people to the DHS website to find out how to make a complaint, but still included the telephone number for the Commonwealth Ombudsman. Many of the people who called us thought they were actually ringing Centrelink. Our complaints staff spent a significant portion of their time answering calls from frustrated Centrelink customers and redirecting them back to Centrelink.

We suggested to DHS that it reinstate the telephone number for its complaint service in its letters to Centrelink customers and in June 2013 DHS decided to do this. Unfortunately, the implementation of change will not be quick: DHS advised us that it will revise the standard text in each of the template letters as and when they are reviewed over the next 18 months.

Diverting callers back to the DHS complaint service

We have adjusted our own work processes to cope with the large numbers of people calling us first to complain about Centrelink. In late 2012 we implemented a new ‘queuing’ arrangement and recorded messaging on our complaints line. This allows us to identify those callers who are ringing us to complain about DHS and to encourage them to call the DHS Feedback and Complaints Line before making a complaint to the Ombudsman. Before these callers are connected to one of our public contact staff, they will hear a recorded message that explains that they have called the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office. The message goes on to say that we are unlikely to be able to help them if they have not already tried to resolve their complaint by calling the DHS Feedback and Complaints Line, and gives them the telephone number for that service.

We think our messaging arrangements have diverted around 5,000 people to the DHS complaint service rather than making a complaint to this office in the first instance. The bulk of those callers would have been ringing us with a Centrelink problem (as distinct from a problem with Child Support or Medicare). Once they obtained the number from our recorded message and called the DHS complaint service, many people have been able to resolve their problem with Centrelink by speaking to the organisation responsible for it. This has been so effective that we actually received fewer complaints about Centrelink in 2012–13 than we did in 2011–12.

Consistent with our telephone messaging strategy, we have also continued to transfer certain Centrelink complaints to the DHS Feedback and Complaints Line so that it can try to resolve them before we will commence an investigation. This ‘warm transfer’ process for Centrelink complaints began in July 2012. We generally make a ‘warm transfer’ if the person who made the complaint to this office has not yet used the DHS complaint service and there is some barrier to them making the call themselves. Sometimes the barrier can be as simple as the cost of making a timed telephone call to DHS from their mobile phone, while other people lack the confidence to call Centrelink themselves. We invite the complainant to contact us again if they are dissatisfied with Centrelink’s response, or if Centrelink fails to contact them within the agreed three-day timeframe (or sooner if the matter is more urgent).

Through judicious use of ‘warm transfers’, and by suggesting that other complainants call the DHS complaint service or use their appeal and review rights to challenge a decision, we have significantly reduced the proportion of Centrelink complaints that require investigation by our staff. In 2011–12 we investigated 24% of the Centrelink complaints that we finalised, while this proportion dropped to 17.4% in 2012–13.

Systemic issues

Own motion investigation into Centrelink service delivery

Although we have reduced the proportion (and number) of individual Centrelink complaints that we investigated, we have taken the opportunity to focus our efforts on some of the more complex systemic problems revealed by those complaints.

Our analysis of our Centrelink complaints data suggested a range of service delivery problems. For example, we received many complaints about unreasonable waiting times on Centrelink’s telephone lines; unclear and confusing computer-generated correspondence; processing delays; delays conducting internal reviews of decisions; and problems getting access to face-to-face service in Centrelink’s offices. In the past we have tended to try to address these problems at an individual level: Chapter 5 of this report includes a series of case studies showing some of those individual investigation outcomes. Unfortunately, fixing problems one case at a time does not always achieve broader, sustained improvements to an agency’s practices.

In May 2013, the Ombudsman wrote to the DHS Secretary to advise that this office would be conducting an own motion investigation into Centrelink’s service delivery. The purpose of the own motion investigation is to test what people tell us about their problems with Centrelink’s service delivery and, as is the case with all such investigations, to contribute to improvements in public administration. We are committed to working with DHS on the issues that we identify and how they can be addressed. The investigation will continue into 2013–14.

Service restrictions

We noticed a slight increase in the number of complaints from Centrelink customers who had been subject to a service restriction, where Centrelink will withdraw or modify the person’s access to its usual service delivery arrangements. Typical service restrictions include limiting a person’s access to face-to-face services; giving the person ‘one main contact’ (usually a senior officer familiar with their case); or limiting a person to ‘write-only’ access. At DHS’ request, we met with some of its Senior Executive to discuss the broader purposes of these service restrictions. These include protecting staff and other customers from abuse or aggression, and ensuring that Centrelink can effectively and efficiently allocate its limited resources in an equitable way.

We have reviewed DHS’ service restriction guidelines (the RSA Decision Making Guidelines 2012) against the key principles that we have set out in a range of published reports and our Better Practice Guide to Managing Unreasonable Complainant Conduct. Overall, we consider that DHS’ guidelines are detailed and thorough, and provide sensible and practical guidance to DHS staff. Service restrictions may only be imposed by senior delegated officers, are usually for short periods, and are subject to review. The customer should be advised of the reasons for the restriction and their right to seek a review of the decision. We will be monitoring the extent to which DHS adheres to its guidelines in managing the challenging behaviour of a very small minority of its customers.

Debt recovery complaints

We have continued our discussions with Centrelink about the issues that we identify in complaints about its debt recovery practices. In 2013–14 we intend to focus on problems with Centrelink’s automated decisions to raise family payment debts on the basis of data (or sometimes the absence of data) from ‘trusted sources’ such as the Australian Taxation Office and the Child Support program. We will continue to raise with Centrelink cases where it appears that the data it is using as the basis for its debt decision is wrong or out-of-date but it is still attempting to recover the debt from the person.

Data transfer problems between Centrelink and Child Support

Last year we reported that DHS had advised us that it had established a Care Review Project. The project was set up to investigate the underlying cause(s) of persistent problems DHS was experiencing in transferring data between the Child Support and Centrelink programs about the ‘care percentage’ (that is, the proportion of time a child spends with each of its separated parents) to be used to calculate those parents’ child support assessment and family tax benefit (FTB) entitlements. We investigated a small number of complaints about this issue in 2012–13 (see, for example, the case studies in Chapter 5 under the heading ‘Data integrity across programs’).

We obtained a progress report from DHS about the Care Review Project in November 2012. DHS advised us that it had already resolved a number of workflow and computer system problems that had been leading to processing errors. It said that further system changes were planned for December 2012 and June 2013. However, there were still significant challenges posed by the need to transfer and apply data to the customers’ records in each of DHS’ separate computer systems (that is, Centrelink, Child Support and Medicare). In February 2013, DHS told us it was looking at ways to integrate the processing of reported changes in care, so that one area of DHS would be responsible for making decisions and implementing the changes on the computer systems for all DHS programs. The number of complaints we receive about incorrect processing of care data seems to be reducing. We will continue to monitor this issue.

Centrelink’s ‘reasonable maintenance action test’ for family tax benefit

Last year we reported that we had been working for some time with Centrelink and Child Support to improve their processes for administering the ‘reasonable maintenance action test’ for the FTB. Under this test, a parent entitled to receive more than the base rate of FTB for a child must take what Centrelink considers to be reasonable action to obtain maintenance (that is, child support) from their child’s other parent. Usually this involves the FTB recipient applying for a child support assessment and collecting all of it privately, or asking Child Support to collect it for them. If the FTB recipient fails the reasonable maintenance action test, they can only be paid the minimum rate of FTB for the child.

Our most serious concern about Centrelink’s administration of this test was the way it explained it to its customers. Centrelink has automated some of the steps for processing new claims for FTB which minimise the chances that a person will miss out on receiving the higher rate of FTB through ignorance or confusion about what Centrelink expects them to do about child support. However, we are still concerned about the way the reasonable maintenance action test is applied in respect of a child who continues to attend secondary school after he or she turns 18. We have investigated several complaints where the child’s parent has missed out on the opportunity to extend their child support assessment after the child’s 18th birthday and, as a result, has had their FTB reduced to the base rate. Taking court action to obtain a child maintenance order for the remainder of the school year is unlikely to be a viable option for the parent with primary care. DHS has advised us that it is in discussions with its policy department in an attempt to identify a solution. We will continue to monitor this problem.

Administration of Income Management

Income Management (IM) has applied in the Northern Territory since 2007, and it is now also in place in some other discrete locations across Australia. IM enables Centrelink to manage at least 50% of a person’s income support payments to ensure they meet their priority needs, and those of their children.

In June 2012 our office released a report Review of Centrelink income management decisions in the Northern Territory, following an investigation into Centrelink’s IM decision making. The investigation considered two kinds of Centrelink decisions: the decision to refuse a person an exemption from IM on the basis that they were considered financially vulnerable; and the decision to apply IM to a person on the basis that a social worker had determined the person to be vulnerable. The investigation identified a number of problematic decisions which stemmed from inadequate tools and guidelines to help decisions makers meet the legislative requirements.

Although the investigation focused on these two areas of decision making, the report highlighted problems that are relevant across all aspects of IM. This included communication and use of interpreters, record keeping, training, and dealing with review and exemption requests. Centrelink accepted the recommendations outlined in the report and had already implemented a number of them by the time the report was released. We undertook to monitor Centrelink’s progress in addressing the issues identified in the investigation and, in late 2012, we conducted a further review of sample decisions. Following this review, we prepared another report for Centrelink which acknowledged the improvements made to date and listed a number of issues that, in our view, remained unaddressed. Centrelink is continuing to work on these areas.

We will continue to engage with Centrelink to monitor its progress. We are also assessing these and other IM issues in our investigation of IM-related complaints. This helps us to identify where individual cases point to a bigger problem that requires fixing. Complaints about IM show examples of where Centrelink has not made the most of opportunities to fix deeper problems and improve its administration of IM. Examples are outlined below.

Despite our report highlighting problems with IM decision making, a recent complaint showed that on review, a Centrelink Authorised Review Officer did not consider the mandatory considerations outlined in the legislative instrument when deciding to keep a person on the ‘vulnerable welfare payment recipient’ measure of IM. A person can be made subject to IM if a Centrelink Social Worker assesses them to be vulnerable and considers that IM will benefit the person. Centrelink has done a lot of work to improve its templates and guidelines to ensure that staff making these decisions are doing so lawfully and correctly, but this complaint shows that further attention is required.

In November 2010 we received a complaint about people paying rent through IM funds for a dwelling that did not attract a rent obligation. This complaint was investigated with the Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) which was responsible for administering the Australian Government’s statutory five-year lease over the community (which subsequently expired on 31 August 2012). This placed FaHCSIA in the position of landlord for community housing. FaHCSIA engaged with Territory Housing and Centrelink in order to resolve the matter. This complaint was resolved, after an 18-month investigation by this office, when Centrelink reimbursed the customer’s IM account with the money that was owed to them by FaHCSIA.

At the time of this complaint investigation, we were informed by FaHCSIA that Territory Housing had implemented a new process for managing requests for rent reimbursement which involved a better and closer working relationship with Centrelink. FaHCSIA also told us that it had fixed the problem to ensure that people living in these kinds of dwellings in this community were no longer paying rent.

In April 2013 we received a complaint about another seven customers who had been paying rent to live in the same dwellings when they were not required to. We investigated this complaint with Centrelink because Centrelink facilitated the rent payments through Income Management. Of most concern was the fact that these seven people all live in the same community as the person who was the subject of the November 2010 complaint, and they are affected by the same problem that was raised in that case. The North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency has been advocating to Territory Housing since January 2011 and Centrelink since January 2012 to have these people refunded their money. We acknowledge that the IM rent deductions for these seven customers had all stopped by April 2012 and that Centrelink’s investigation may be complicated because the housing association that collected the rent has told Centrelink that it reimbursed the customers through credits at the local store. However, the issue remains unresolved for the customers affected.

These cases highlight a number of issues across the agencies involved:

- the agencies did not take adequate action to ensure that rent being collected from Indigenous people living in remote communities was in accordance with the policy

- Centrelink paid customers’ IM funds to third parties when there was no requirement for the customer to

pay rent - Centrelink’s processes did not ensure that third parties who were receiving IM funds operated within the bounds of the contract

- the agencies have been slow in their resolution of these cases and people have been out-of-pocket since 2008 when the payments started.

In another IM-related complaint made to this office, Mr A, who usually lives in Victoria, travelled to the Northern Territory to visit his daughter. Being a resident of Victoria, Mr A is not eligible for the IM scheme. While in the NT, he visited a Centrelink office and was told that he needed to update his address. Centrelink changed his permanent address to the NT address on its system. This meant that Mr A erroneously became eligible for IM. Centrelink sent Mr A an automatically generated letter advising that he was due to go onto IM, but he did not receive it.

Mr A told us that he approached Centrelink on numerous occasions, both in person and by phone, when he returned to Victoria because he noticed that he was only receiving half of his usual Centrelink payment and he was in financial hardship. Despite his repeated contacts with Centrelink, Mr A told us he was unable to resolve the matter. Following an investigation by this office, the issue was resolved and Mr A’s income-managed funds were returned to him. Centrelink also arranged for a social worker to assist Mr A with his housing and financial issues at our suggestion.

Complaints about IM show that Centrelink has improved its communication surrounding IM, it has enhanced the capacity for people to access their IM funds and it is assisting more people to apply for exemptions. However, complaints indicate that Centrelink could further improve its administration of IM by:

- quickly fixing problems for people, particularly where Centrelink has made an error

- looking at the entirety of a person’s case to determine the most appropriate response to their circumstances

- escalating entrenched or difficult cases

- ensuring that decision making meets legislative obligations

- improving systems to better capture the circumstances of its customers

- learning from its mistakes.

Reports and submissions

(see Chapter 6)

Published report of an investigation: Ms Z

In February 2013 we published a report, Department of Human Services (Centrelink): investigation of a complaint from Ms Z concerning the administration of youth allowance. Ms Z was a homeless 16-year-old girl who approached Centrelink for financial assistance. Centrelink eventually decided she qualified for youth allowance at the ‘unreasonable to live at home’ rate, but she experienced a series of delays and errors that left her without regular payment. Those delays and errors were attributable to Centrelink’s failure to manage her case appropriately. In this case, Centrelink failed to use the procedures it has developed precisely to assist people like Ms Z, both to assess whether they are entitled to receive a payment and to meet various procedural requirements (such as proof of identity checks and obtaining a tax file number). Our investigation led Centrelink to review and strengthen its processes and apologise to Ms Z.

Submissions

Our office often draws on themes and issues identified in our complaint investigations to make submissions to inquiries about a range of government services, programs and policies. In this reporting period, we made a submission to DHS’s independent review of the Centrepay Scheme1 and another submission to FaHCSIA about its exposure draft in relation to the Public Housing Tenants Support Bill (establishing the Housing Payment Deduction Scheme).

Common to these schemes is the capacity for a person’s Centrelink benefit to be directed to third parties, although Centrepay is voluntary and the Housing Payment Deduction Scheme, if introduced, is not. The concerns discussed above in relation to IM and Centrelink’s service delivery also informed our submissions on these matters.

Centrepay

Centrepay is a voluntary and free bill paying service for recipients of Centrelink payments. Centrepay is the mechanism by which Centrelink makes automatic deductions from a person’s payment and transfers those amounts directly to a third party to cover the person’s bill or other expenses.

In our submission 2 we acknowledged the obvious benefits and convenience that the Centrepay scheme offers to Centrelink’s customers. However, these benefits are diminished when systems established to administer the scheme cause adverse consequences for customers. Examples covered in our submission included:

- Centrelink assigning part of a person’s Centrelink payment to a third party without first obtaining consent from the customer. We believe that without consent, the inalienability of a person’s Centrelink payment is compromised. Complaints to our office where this has occurred have shown that people have been left out-of-pocket and have found it onerous and slow to get the Centrepay deductions stopped and the money returned

- vulnerable customers being open to exploitation or financial hardship as a result of a third party organisations adopting inappropriate practices in order to sign people up to Centrepay. While we accept that Centrelink is not responsible for ensuring these third party organisations comply with state-based consumer protection laws, the ease with which these types of traders appear to be able to access guaranteed payment for their goods through Centrepay requires attention

- Centrelink doing more to help vulnerable customers access the best service for their needs. Centrelink customers will not necessarily know the range of services and assistance that Centrelink provides. Instead of simply facilitating a Centrepay deduction at the customer’s request, an integrated approach to helping a customer manage their money and receive a service that most suits their needs should include discussing the range of options or support services available to them to find the best option for their circumstances

- instances where customers, particularly those who are vulnerable, have Centrepay deductions that amount to 80% or more of their payment. We suggested that Centrelink consider ways it could be alerted to situations where deductions amount to a significant percentage of a person’s payment and alerting the customer to this, or assessing whether they may need extra assistance.

We are particularly interested in the outcomes of the independent review and any strategies identified to improve the scheme. We will continue to engage with DHS where we identify issues with the scheme.

Housing Payment Deduction Scheme

The Australian Government released an exposure draft of the Public Housing Tenants Support Bill 20133 which establishes the Housing Payment Deduction Scheme. The Australian Government described the scheme as being aimed at helping to prevent evictions and possible homelessness of public housing tenants due to unpaid rent. If reintroduced, the Bill would allow public housing costs that have to be paid under a public housing lease to be deducted from the lessee’s income support payment, providing they are either in arrears or are at risk of arrears4.

The main concern outlined in our submission5 was the risk that the scheme, if implemented, would be used to collect from public housing tenants debts that are unconfirmed, disputed or have not been through the appropriate state/territory-based channels for recovery. We also expressed concern about the lack of engagement with the person affected in the decision-making process and the need to ensure procedural fairness and a thorough assessment of a person’s individual circumstances before applying the scheme.

In our submission we also warned that complaint investigations by this office about other programs that require cooperation and coordination across levels of government show that weaknesses in the administrative arrangements between agencies or levels of government can cause confusion and other significant problems. We reiterated that if the proposed scheme is introduced, it is critical that robust and clear processes between the agencies involved are implemented first, and that clear lines of accountability are well established.

This office will monitor the developments in relation to this scheme and will engage with FaHCSIA and DHS to ensure that, if it is implemented, the administration underpinning it is sound.

Indigenous stakeholder engagement

One of our key objectives is to make the Ombudsman’s complaint services more accessible to Indigenous people living in remote locations. We aim to achieve this by conducting outreach visits to Indigenous communities, distributing material advertising our role, and engaging with stakeholders who provide services to Indigenous people to assist in the referral of complaints. We have continued to meet with the National Welfare Rights Network, Welfare Rights Centres, legal and advocacy services (in particular, the North Australian Aboriginal Justice Agency) and other support services, both in the Northern Territory and more widely.

We have also now established contact with the National Congress of Australia’s First Peoples and the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, and we are looking forward to building those relationships.

We are committed to increasing our connections with organisations that work with or represent Indigenous people, particularly those living remotely. This helps to alert us to new problems or gain a deeper understanding of the impact of government programs, services and decisions.

The office aims to make Ombudsman complaint services more accessible to Indigenous Australians. Famous Indigenous ex rugby league player, Steve Renouf, lends his support to outreach in Queensland in 2013. Steve is pictured with a member of the Ombudsman’s Indigenous team.

Stakeholder engagement, outreach and education

Our engagement with Centrelink extends beyond our investigation of individual complaints. We have quarterly liaison meetings with DHS to discuss a range of issues arising from our investigation of complaints about all of its programs, but particularly Centrelink and Child Support. We supplement these quarterly meetings with ad hoc meetings, frequently using teleconference or video conferencing facilities, to explore particular issues in more detail. We also obtain written and oral briefings from DHS subject matter specialists about systemic problems and to pursue ‘issues of interest’ that we identify in the complaints that we receive.

Throughout the year we continued to have ad hoc contact and meetings with the National Welfare Rights Network to discuss matters of mutual interest related to Centrelink’s administration. Officers from our Community Services Branch attended the annual conference of the Australian Council of Social Services in Adelaide in April 2013 to hear more about the experiences of people who are customers of Centrelink but may not approach our office when they have problems.

We attended meetings of the DHS Consumer Consultative Group and Service Delivery Advisory Groups, in an observer capacity. Our office is also a member of the Child Support National Stakeholder Engagement Group, and attended three meetings this year which considered matters relating to the administration of the Child Support scheme and the family payments system administered by Centrelink.

Child Support

Child Support assesses and transfers child support payments between separated parents of eligible children. If a child lives with a person other than his or her parents (for example, a step-parent or foster carer) that carer can apply for an assessment of child support payable by the child’s parents. Child Support also registers and collects court-ordered spousal and child maintenance payments, and some overseas maintenance liabilities.

The Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about Child Support’s administration of a child support case. However, the Ombudsman cannot investigate complaints about the actions of a private citizen who is a party to a child support case. We sometimes need to explain this distinction to the people who contact us to complain about their child support case.

Complaint themes

In 2012–13 we received 1,736 complaints about Child Support. This is 28% fewer than in 2011–12, when we received 2,228 Child Support complaints. We investigated approximately 19.3% of the Child Support complaints that we finalised in 2012–13, compared to just over 29% in 2011–12.

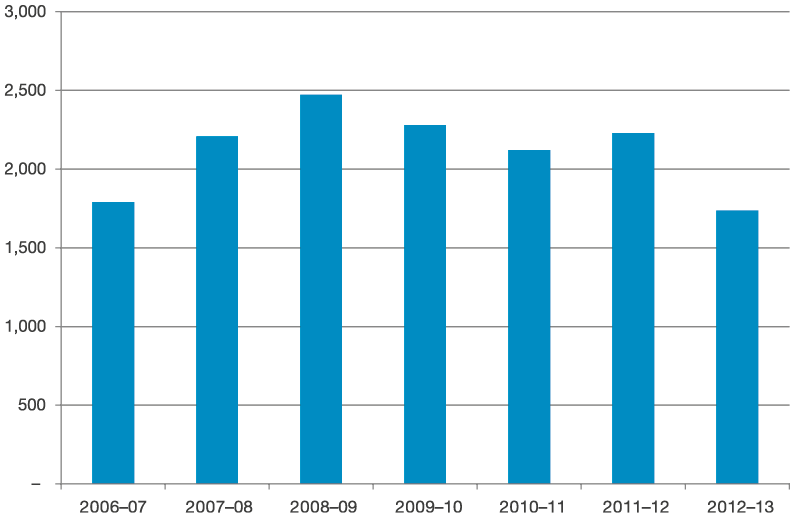

Figure 4.2: Number of complaints and approaches about Child Support from 2006–07 to 2012–13

This chart shows the number of complaints and approaches about the Child Support Agency made to our office from 2006–07 to 2012–13. These are: 1,790 in 2006–07; 2,208 in 2007–08; 2,471 in 2008–09; 2,280 in 2009–10; 2,121 in 2010–11; 2,228 in 2011–12 and 1,736 in 2012–13.

Who is complaining?

We classify the issues in the complaints that we receive about Child Support according to whether the complaint was made by the payee (that is, the person entitled to receive child support) or the payer (that is, the person obliged to pay child support). In 2012–13, 28% of the child support issues that we finalised were in complaints made by the payee (or someone on the payee’s behalf). Almost 70% of the child support issues were in complaints made by the payer (or someone on the payer’s behalf).

The proportion of complaint issues raised by payers has increased since 2011–12, when the ratio of payer to payee complaints was roughly 2:1. However, there has not been any significant change in the nature of the issues that people complain about: they continue to be about the amount that people are assessed to pay or receive, and the actions that Child Support takes to collect these sums.

Fewer complaints about Child Support

We are unable to point to a single cause for the reduction in the numbers of people contacting us to complain about Child Support. One likely factor is that there have been no major legislative policy or administrative changes affecting the Child Support scheme, so it was a fairly settled year for the Child Support program. There are still some problems associated with the transfer of data between Child Support and Centrelink (which we have discussed earlier in this chapter under the headings ‘Data transfer problems between Centrelink and Child Support’ and ‘Centrelink’s ‘reasonable maintenance action test’ for family tax benefit’) the DHS Care Review Project has led to improvements, and the remaining problems tend to have a greater impact on a person’s Centrelink payments than their child support case. We were pleased to note a significant reduction in the number of complaints about Child Support incorrectly applying data from Centrelink about the percentage of time a child spends in the household of his or her separated parents. This had been a persistent problem since July 2010.

We also note that the extensive delays that people experience when waiting on the telephone to speak to a Centrelink office are not affecting other DHS programs, such as Child Support. Child Support customers rarely, if ever, complain to us about telephone delays. Another difference between the DHS Child Support and Centrelink programs is that Child Support has been much more open in promoting and encouraging its customers to phone its complaint service if they are dissatisfied with the way their case is being managed.

We are also conscious that, before DHS integration, Child Support staff were strongly encouraged to identify, resolve and escalate complaints using the agency’s internal three-step complaints process. It is also likely that a proportion of the people who have called us to complain about Child Support since December 2012 have gone back to the DHS complaint service after listening to the recorded message that we play to each caller (see the discussion earlier in this chapter in relation to Centrelink).

Warm transfers

In our 2011–12 annual report we said that we expected to introduce a process to directly transfer some of the complaints we receive about Child Support to its internal complaint service for resolution. This ‘warm transfer’ process began in August 2012. We obtain the complainant’s consent to the transfer, and invite them to contact us again if Child Support fails to contact them in the agreed time (three days, or shorter for urgent cases), or if they are dissatisfied with Child Support’s response to their complaint.

Consistent with our approach to complaints about Centrelink, through judicious use of ‘warm transfers’ and by suggesting that other complainants call the DHS complaint service, or use their objection and appeal rights to challenge a decision, we have significantly reduced the proportion of Child Support complaints that require investigation by our staff (from just over 29% in 2011–12 to 19.3% in 2012–13).

Overseas cases

In our 2011–12 annual report we discussed our concerns about Child Support’s administration of cases where one of the parents is located outside Australia. We observed that the complaints we had received suggested that Child Support’s administration of some overseas cases was marred by communication problems, delays or a general lack of responsiveness.

Our analysis of the complaints that we received this year about Child Support’s administration of overseas cases suggests that things may be improving. There were very few complaints about recent communication problems for overseas cases. However, we are currently investigating one complaint where Child Support’s failure to communicate over many years with a paying parent living overseas left that person with a very large Australian child support debt. This is despite the fact that the parent paid what he was ordered to pay by the courts in the country where he lived, which seems unfair. We are exploring what remedy, if any, Child Support can offer this complainant.

Payee overpayments

In last year’s annual report, we mentioned our work in relation to Child Support’s administration and recovery of payee overpayments. At that time, we were investigating several complaints involving Child Support recovering money from the payee to repay to the payer. In each of those cases, the payee’s overpayment was solely attributable to actions of the payer. Two payers had moved to live in countries with which Australia had no maintenance agreement, so their Australian child support assessments ended retrospectively. A third payer lodged a number of overdue tax returns after his children reached adulthood and his child support case had ended. His taxable income was lower than he had originally declared to Child Support, and this resulted in a retrospective change to his child support assessment.

We advised Child Support and FaHCSIA (the department with policy responsibility for the Child Support scheme) of our reservations about their view that the Australian Government was obliged to recover every overpayment of child support. We also expressed our opinion that in each of these cases, it was inequitable for the Australian Government to recover from the payees, who had received the child support payments in good faith and already spent the money on the children.

We are pleased to report that after considering our view, Child Support and FaHCSIA decided that the Australian Government should not recover our complainant’s overpayments, or other overpayments occurring in similar circumstances. Child Support and FaHCSIA cooperatively developed procedures to support this change in policy, for implementation from mid-June 2013. We will be seeking reports from Child Support about its implementation of the new overpayments policy. We also intend to monitor the complaints we receive in future for other situations where it may not be appropriate for Child Support to recover an overpayment from a payee.

We should clarify that it is not our view that Child Support should never recover a payee overpayment. In most situations, the overpayment is legally repayable to the Australian Government and Child Support has a legal obligation to recover it from the payee and, in turn, refund the recovered sums to the payer. Child Support is entitled to take certain administrative recovery actions to recover a payee overpayment, for example, by withholding amounts from the payee’s ongoing child support payments, or a tax refund, or asking Centrelink to make deductions from the payee’s pension or benefit. However, we are aware that Child Support’s computer system does not currently support it to use the full range of administrative recovery options.

We also have a range of concerns about Child Support’s procedures for calculating and raising overpayments; notifying the payer and payee of the overpayment; negotiating the rate of repayment; and administering the recovery arrangement. We wrote to DHS in March 2013 identifying what we consider to be weaknesses in Child Support’s procedures for administering and recovering overpayments. We intend to continue working with Child Support to help it improve this area of its administration.

Compensation for missed child support

Last year, we reported our intention to continue our efforts to persuade Child Support to change its approach to claims from payees for compensation for a missed collection opportunity. This occurs when Child Support, through its own error, or through a deficiency in its procedures, fails to collect a sum from a payer. The cases where this happens are quite rare, as it requires a certain collection opportunity that Child Support should have seized but failed to. When it happens, the payee has missed out on the benefit of receiving the sum at the time, but Child Support can still collect it for them in future, when (or if) the opportunity arises. This could be in many years’ time, or even never.

We investigated a complaint this year where this problem arose. We suggested that Child Support consider compensating the payee for the amount that it failed to collect, in return for the payee agreeing to allow Child Support to keep the money when it eventually collected it from the payer. Child Support told us that it does not consider the payee has suffered a loss, but merely a delay. Child Support conceded that the sum might not be as valuable if and when it eventually collects it, and it said that it would consider compensating the payee for any loss in value. However, this loss in value will not ‘crystallise’ until Child Support finally collects the money.

Child Support obtained written support from the Department of Finance and Deregulation (Finance) for its approach to this particular complaint. We remain unconvinced that this approach is fair, particularly if Child Support never collects the sum and the payee’s loss never ‘crystallises’. We met with Finance in June 2013 to discuss Child Support’s approach to claims for compensation for missed collection opportunities, and whether this was in keeping with the restorative aim of the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration scheme. We will continue to work on this issue, in consultation with Child Support and Finance.

Early release of superannuation benefits

We finalised 122 complaints in 2012–13 about DHS’ processing of applications for early release of compulsorily preserved superannuation benefits on compassionate grounds. The most common issues in those complaints were delays in processing applications and decisions that the applicants believed were unfair.

In two cases our investigation led DHS to reconsider and change its decision to refuse to approve early release of the applicant’s superannuation. In the course of our investigations, we have commented on the clarity and completeness of the guidelines that DHS has published to assist staff to make decisions on applications which raise complex issues. In May 2013, DHS advised us that it would be reviewing these guidelines in 2013–14 and that it will seek our comments on the revisions before they are finalised.

1The (then) Minister for Human Services, Senator the Hon Kim Carr announced an independent review into Centrepay in November 2012.

2www.humanservices.gov.au/corporate/government-initiatives/centrepay-review/

3The Bill was subsequently introduced into the Parliament as the Social Security Legislation Amendment(Public Housing Tenants’ Support Bill) 2013, however it lapsed when the Parliament was prorogued on 5 August 2013.

4www.fahcsia.gov.au/our-responsibilities/housing-support/programs-services/homelessness/exposure-draft-public-housing-tenants-support-bill-2013

5www.fahcsia.gov.au/our-responsibilities/housing-support/programs-services/homelessness/exposure-draft-public-housing-tenants-support-bill-2013

Australia Post

The Postal Industry Ombudsman’s jurisdiction includes the investigation of complaints about Australia Post. As an industry ombudsman, the Postal Industry Ombudsman also investigates complaints about private postal services.

In 2012–13, we received 3,652 complaints and approaches about Australia Post which constitutes 20% of the total complaints and approaches made to our office.

A discussion about complaint themes and the systemic issues we pursued with Australia Post is included in Chapter 7 with the overview of the specialist functions of the Postal Industry Ombudsman.

Australian Taxation Office

Overview

The Taxation Ombudsman role was created in 1995 to increase the focus on the investigation of complaints about the Australian Taxation Office (ATO).

The Taxation Ombudsman appears at the annual hearings of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit with the Commissioner of Taxation, and provides a review of the ATO’s performance based on the complaints we receive and our liaison activities with the ATO. The role does not otherwise confer any additional duties or functions under the Act.

Complaints about the ATO

In 2012–13 we received 1,795 complaints about the ATO, which represents a decrease of almost 34% on complaints received in 2011–12. Overall, complaints about the ATO accounted for 10% of the complaints we received during the year.

Recognising that the most efficient way to resolve time-sensitive complaints is to raise them with the agency concerned, we reviewed and changed our procedures and the introductory messaging on our telephone systems, to better inform and redirect first-time complainants. As a result, the percentage of these complaints reduced from around 50% to less than 20%.

Approximately 50% of complainants approach the Ombudsman without having first raised a formal complaint with the ATO. This is higher than the 40% who do so in relation to other comparatively sized agencies.

A review conducted in conjunction with the ATO revealed that a common feature of these complaints was a time-critical element—for example, a delay in the issue of an income tax refund. In such cases, complainants tended to contact the ATO more than once to enquire about the progress of their return and, if they were not successful, they sought the help of the Ombudsman instead of lodging a complaint with the ATO.

The ATO has escalation processes to quickly address delays and a separate process to prioritise refunds for those in financial hardship. Lodging a formal complaint with the ATO ensures that taxpayers’ issues can be appropriately addressed quickly through these processes.

Work continues to provide further improvement in 2013–14.

Complaint themes

The most common ATO complaints received related to:

- delays in income tax refunds

- administrative overpayments

- debt collection

- superannuation.

Income tax refunds

The annual lodgement of income tax returns and the impact of the ATO’s Income Tax Return Integrity checking activity remain significant factors in complaints about the ATO.

The ATO uses specialist technology to identify and check income tax returns that may contain missing or incorrect information. Tax refund claims, which the ATO identifies as falling outside of typical parameters, may result in a thorough review of all aspects of an individual’s tax affairs before a refund is issued. This can often lead to a delay in issuing the refund, even if the ATO ultimately determines that all is in order.

The effect of Income Tax Return Integrity checking first came to the attention of the Ombudsman in 2011, following an influx of complaints concerning delays. In response to investigations and meetings with our office, the ATO undertook to improve its service delivery by, among other things, improving its communication with taxpayers and tax agents.

We are pleased to note that the ATO took into account the feedback provided by this office and has improved its communication with taxpayers.

In 2012–13 complaints relating to lodgement and processing issues accounted for almost 26% of all ATO complaints.

Administrative overpayment

During the year we investigated a number of complaints about overpayments made by the ATO as a consequence of an error caused by a system change.

Taxpayers who had included a lump sum payment (their final pay from their employer) in their tax return approached the Ombudsman after receiving a tax bill from the ATO as a result of an ATO systems error. The taxpayers had initially received a larger than expected tax refund and had contacted the ATO to check and confirm that the refund was correct. The ATO confirmed that the refund was correct and the taxpayers planned their finances accordingly.

However, the following year, the ATO contacted the taxpayers and informed them that a systems error had caused incorrect refunds to be issued. The taxpayers had, in fact, received larger refunds than they were entitled to, and now owed the excess amount to the ATO.

The ATO acknowledged that while the situation was caused by a systems error, the Tax Administration Act 1953 does not allow it discretion to release a taxpayer from a debt created in these circumstances. The ATO offered an apology to those affected and worked to establish practical repayment arrangements to recover the debts.

While we recognise that system errors can occur, we consider that as a general principle, a taxpayer acting in good faith should be able to rely on information provided by the ATO call centres.

Although the system error has since been fixed, we continue to work with the ATO to reduce the impact on taxpayers through early detection, better communication and identifying available measures to mitigate any financial detriment.

Debt collection

Multiple accounts

Debt collection remains a persistent cause of complaints to the Ombudsman. In 2012–13 around 23% of ATO complaints related to the ATO’s debt collection issues.

A common theme identified by our office involved complainants who said that they only became aware of the debt after being contacted by a debt collection agency or after their bank account was garnisheed. The debt usually related to Pay As You Go instalment accounts rather than an income tax debt. We established that the problem typically related to multiple accounts maintained by the ATO for the taxpayer—for example, in relation to Pay As You Go, income tax, goods and services tax or superannuation. Taxpayers, however, are frequently unaware of the separate accounts or the need to update contact information relating to each of those accounts.

The ATO agreed to ensure that call centre staff inform callers wanting to change their address of the need to update their contact details in respect of other accounts, if they have them. The ATO also agreed to expand the information on its website concerning change of address, to provide a more practical guide.

The ATO advised us during the year that work was well underway to introduce a new online service which would allow individual taxpayers to access and update their personal tax information and transactions. This service was introduced in April 2013.

Director liability

Since the expansion of the director penalty legislation in June 2012, the ATO has been able to hold company directors personally liable for both the income tax withholding and superannuation obligations of the company. This was an important step in counteracting ‘phoenix’ activity, where companies could close down and re-open as a new entity, leaving unpaid withholding tax and superannuation contributions. It also means directors can be held liable in circumstances where they have failed to honour their responsibilities as a director. However, the issue of personal liability can become clouded in cases of family companies where, following a marriage breakdown, husband and wife directors reach an agreement in the Family Court.

The Ombudsman received complaints from individuals who, as part of a divorce settlement, reached an agreement that one party became solely responsible for the debts of the company in exchange for the other party giving up company ownership or directorship.

The ATO advised that it is not bound by Family Court decisions as it is not a party to these decisions. The appointment and cessation of a director is the responsibility of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, which is the ATO’s source of information on the registration status of a company and relevant director appointment dates. The ATO maintains that, while the individual is registered as a director, they remain liable for company debts relevant to their period of directorship, and a director penalty notice can be issued.

We do not consider it unreasonable for the ATO to issue a director penalty notice to a currently registered director. However, we have asked the ATO to consider the advice it provides to taxpayers in these circumstances, particularly around referral to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission for advice on the question of registration or to seek independent legal advice.

Superannuation

In 2012–13 nearly 10% of complaint issues we recorded related to superannuation and unpaid superannuation guarantee payments.

Complaints about unpaid superannuation contributions are typically made by employees who are unhappy with the ATO’s response to their enquiry. Concerns often focus on delay, lack of information or uncertainty about the ATO’s progress towards collecting unpaid superannuation.

Investigations conducted by the Ombudsman revealed that the ATO treats enquiries about unpaid superannuation seriously but privacy and taxpayer confidentiality provisions restrict it from providing information concerning the tax affairs of another party (the employer) to anyone other than that person or an authorised representative.

Overall, we found that the ATO follows due process in dealing with superannuation enquiries and has recently reviewed its advice letters to improve their clarity.

Other matters

Communication

We continued to provide feedback to the ATO in relation to its letters and other communication with taxpayers.

The ATO undertook a special project to identify and review the top 10 letters that generate contact with its call centres or complaints. The ATO continues to consult the Ombudsman on the progress of the project which is well advanced and covers a cross-section of topics.

During the year we raised with the ATO the issue of providing prompt advice to taxpayers of system errors or outages, particularly those which the ATO considers may lead to processing backlogs or unavoidable delays. For example, a problem with the tax file number registration system led to a backlog in registrations work, resulting in applicants experiencing a delay in receiving their tax file number.

The Ombudsman received a small but significant number of complaints regarding this delay. We suggested to the ATO that providing early advice of the delay on its website would likely reduce the need for applicants to contact its call centres and may prevent subsequent complaints.

We note that the ATO has successfully applied the early advice principle, particularly in the Income Tax Return Integrity program, where communication has improved overall.

E-tax lodgement using non-windows-based operating systems

Complainants have approached the Ombudsman over several years about the lack of availability of the ATO’s e-tax system to those who use Apple Mac or Linux operating systems.

The ATO advised our office that it intended to make e-tax available to the other platform users but that a major systems upgrade was underway and further work will be undertaken following the upgrade. It advised that it had included the operating system upgrade as part of its five-year forward work plan.

The ATO also advised that information on its website explains that taxpayers could purchase emulation software that make Apple Mac and Linux operating systems e-tax-lodgement-capable. The cost of the purchase is tax deductible; however, the taxpayer could only claim that portion of the cost that was related to preparing and lodging the return or managing tax affairs.

We suggested to the ATO that while the possibility of tax deductibility is an advantage, the apportionment—if the purchased program is used for purposes other than using e-tax—makes this option unnecessarily onerous. The options available to those affected are to use an e-tax machine at an ATO shopfront; to use the services of a tax agent; to lodge a paper return; or to outlay money to purchase software. We noted that the lack of availability of e-tax did not make it easier for these taxpayers to comply with their lodgement obligations. The ATO undertook to give due consideration to the matter and subsequently advised that e-tax would be available for Apple Mac users from 1 July 2013.

Department of Immigration and Citizenship

Complaints

Complaints about the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) decreased in this financial year. Overall, we received 1,547 complaints about DIAC compared to 1,873 in the 2011–12 financial year and 2,137 in the 2010–11 financial year. We finalised 1,547 complaints in 2012–13.

DIAC’s internal complaint handling process is through its Global Feedback Unit. Our office, in consultation with DIAC, has recently introduced a ‘warm transfer’ process. Under this process, certain complaints are transferred back to DIAC’s Global Feedback Unit for resolution in the first instance or to give DIAC a second opportunity to resolve the complaint where we think that is the appropriate course of action. This process builds a collaborative relationship between us and DIAC and is designed to ensure quicker and more efficient resolution of complaints.

We investigated 16% of complaints received about DIAC in 2012–13 compared with 15% in 2011–12, and we were able to facilitate remedial action in 60% of these cases. Complaints by people in immigration detention accounted for 24% of complaints we received about DIAC and we investigated 43% of these complaints.

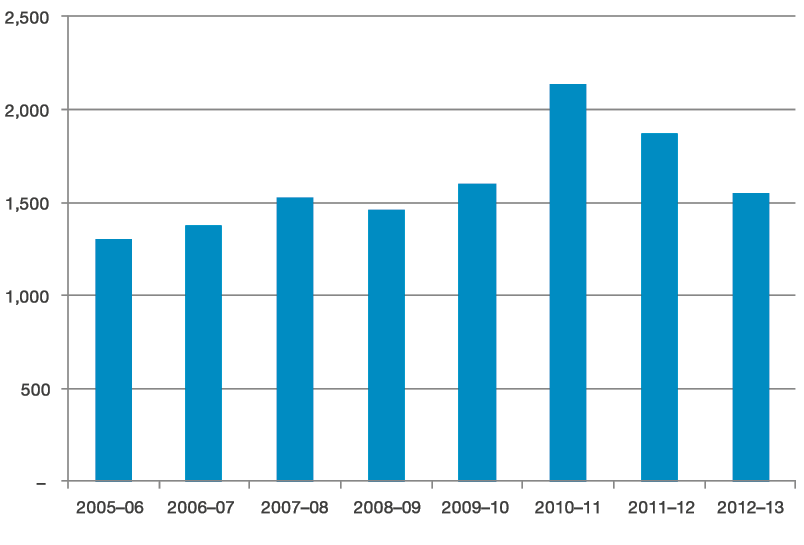

Figure 4.3: Number of complaints and approaches about the Department of Immigration and Citizenship from 2005–06 to 2012–13

This chart shows the number of complaints and approaches about the Department of Immigration and Citizenship made to our office from 2005–06 to 2012–13. These are: 1,300 in 2005-06; 1,379 in 2006–07; 1,528 in 2007–08; 1,459 in 2008–09; 1,600 in 2009–10; 2,137 in 2010–11; 1,873 in 2011–12 and 1,547 in 2012–13.

Our complaint investigation this financial year has achieved positive outcomes for some individuals, such as:

- better explanations for some decisions

- refunds on visa application costs

- highlighting errors which have resulted in DIAC departing from the original decision and making a fresh decision

- assisting visa applicants in cases where there was unexplained delay beyond service standards.

Engagement with DIAC

We regularly meet with DIAC’s Ombudsman and Human Rights Coordination Section in order to resolve systemic issues affecting good administration. DIAC also provides our office with regular briefings about developments in immigration policy and legislation, such as visa pricing changes. We have continued to attend high-level quarterly meetings with DIAC which provide an opportunity to discuss emerging issues and any concerns that we have identified during our inspection and review activities.

Complaint themes and systemic issues

Perceptions of delays, deficient advice and incorrect decision making continue to generate the majority of complaints in relation to both detention and migration programs generally. Many complaints relate to services delivered by non-government service providers on behalf of DIAC. The majority of complaints concerning migration programs relate to applications for family visas or skilled visas.

The Ombudsman identifies recurring issues through complaints and monitors these through an Issues of Interest register. An example is the refusal of visa applications based on the genuine visitor and genuine student criteria to ensure consistency in the application of ‘genuineness’ criteria.

Service delivery in immigration

Delay in processing

One of the main causes of complaints to this office is perceived delays in finalising processing on immigration matters. Complaints about delays have related to a range of activities, including visa processing for Family, Business and Tourist Visas; complaint handling by DIAC’s Global Feedback Unit; completion of medical clearances; refugee status assessments; access to property in immigration detention; and access to health services by detainees.

Our complaint investigations function at times highlights delays occurring in particular overseas posts or in relation to a particular group. By investigating such complaints we assist DIAC in determining the cause of delay and whether or not the delay is systemic in nature and likely to affect a large number of people. This, in turn, facilitates remedial action.

The case study about Mr BB ‘policy not followed’ in Chapter 5 illustrates the difficulty in identifying the cause of delays in some circumstances, and the importance of providing clear pathways for escalating complex applications or unusual issues.

Deficient advice

Another common source of complaints we receive about DIAC is inaccurate or incomplete advice, or the perception of inaccurate and incomplete advice. We acknowledge that the complexity of law and policy relating to immigration presents a challenge to the provision of clear, accurate and complete advice. This is especially true where staff are giving advice across a range of programs to clients who come from a wide variety of backgrounds, some with specific vulnerabilities such as lack of English language comprehension.

The role of DIAC’s Global Feedback Unit in clarifying or correcting deficient advice is often crucial to restoring the client’s relationship with, and trust in, the agency. Examples of deficient advice which emerged from complaint investigations this year included:

- incorrect advice about review rights in a letter template

- incomplete advice about entitlement to a refund

- incomplete advice about options in relation to visa applications and processing.

The case study about Ms FF ‘visa confusion’ is an example of how incomplete advice can cause less than optimal outcomes for clients.

Relationships with contracted service providers

Like many government agencies, DIAC provides a range of services through non-government service providers that are private sector or community organisations. The management of services through third parties presents a challenge for accountability and governance in the delivery of public services. The service provider may be delivering the service and interacting with service recipients but DIAC generally retains statutory responsibility for ensuring that the service is delivered in accordance with legislative and policy requirements.

Among other things, DIAC engages service providers to:

- operate detention facilities

- provide re-settlement services for refugees

- provide health services for people in immigration detention

- provide medical assessments to visa applicants.

We receive complaints from people about the provision of these services and about DIAC’s handling of complaints about service providers. Proactive engagement with service providers—through measures such as training and regular consultation—will influence the extent to which services are delivered appropriately. The management of complaints about third party providers is also a tool for ensuring accountability in service delivery.

Oversight of third party service providers was also a theme in the Suicide and self-harm in the immigration detention network report issued by the Ombudsman in May 2013. This report highlighted, among other things, the limitations in DIAC’s system for collecting and reporting data from service providers about the incidence of serious self-harm. In order to address this problem, DIAC has conducted a review of the detention service provider’s delivery of incident reporting to assess the quality, accuracy and timeliness of incident reporting and has agreed to conduct post-incident reviews. DIAC has advised our office that it is proposing to implement best practice incident management reporting in immigration detention facilities.

The case study about Ms HH ‘lost complaint about settlement’ in Chapter 5 is an example of proactive complaint handling by DIAC in relation to a complaint about a third party service provider.

Immigration detention inspections

Details of the immigration detention facilities that our office inspected are included in Chapter 7 of this report. During the course of the year, we have noted a consistently high operational tempo across the immigration detention network. Despite the increased level of operations, we noted an overall improvement in function and processing in the immigration detention network, in particular:

- a high level of movement of detainees from Christmas Island to mainland facilities and into the community on Residential Determinations or Bridging Visas

- a significant decrease in incidents of self-harm across the network

- the introduction of network-wide detainee property management guidelines

- a network-wide improvement in the management of detainee welfare

- the introduction of a network-wide programs and activities framework that has an increased focus on the provision of meaningful activities for detainees

- improvements in the administration and management of the Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation and Scherger Immigration Detention Centre

- improvements in the management of transport and escort functions in Darwin, Scherger and Brisbane immigration detention facilities

- an ongoing willingness of staff and detainees in the respective facilities to work together to address issues and complaints.

We remain concerned about the use of immigration detention facilities that are located in remote and isolated areas of Australia. These include the Scherger Immigration Detention Centre outside Weipa (Queensland), the Curtin Immigration Detention Centre outside Derby (Western Australia) and Christmas Island (Indian Ocean Territories).

We are also concerned about overcrowding across the detention network, with a number of facilities at—or exceeding—their contingency capacity at the time of this report. The manner in which the Enhanced Screening Process is applied to certain groups of irregular maritime arrivals is a matter for concern, as is the ongoing management of long-term detainees and those who remain as a ‘person of interest’.

With regard to the amenities at immigration detention facilities, we note with concern:

- the ongoing use of ‘temporary’ facilities to house family groups on Christmas Island

- the absence of suitable sporting and recreational facilities in the Aqua and Lilac compounds on Christmas Island

- a deterioration of facilities for family groups and unaccompanied minors on Christmas Island

- the limited facilities available for family groups at Curtin Immigration Detention Centre

- the ongoing concerns about security provisions at Scherger.

We also noted inconsistencies and varying quality in administrative processes and procedures applied across the network. Areas of concern included methods of managing detainees’ property, risk assessments, incident reporting, Individual Management Plans, case notes and supporting documents.

In addition, we noted some concerns about transport processes and procedures, including:

- Transport and Escort Movement Orders

- the notification and processing of transfers from Australia to Regional Processing Centres

- processes surrounding the management of air transfers and direct boat arrivals in Darwin

- procedures on Christmas Island to disembark new arrivals when the boat ramp—rather than the jetty—is used during monsoonal weather.

Reports and submissions

The Ombudsman released a report under section 15 of the Ombudsman Act in May 2013. This followed an investigation that was prompted by several deaths and incidents of self-harm in detention facilities, along with observed deterioration in the psychological health of detainees, particularly on Christmas Island. (See Chapter 2 and Chapter 6 for details on this report.)

Future/emerging issues

In relation to our immigration oversight role, we envisage that one of our priorities in 2013–14 will be to monitor DIAC’s compliance and removal activities. Particular areas of focus will include the use of warrants in DIAC’s compliance activities and the removal of people from Australia who have had their visa cancelled under section 501 of the Migration Act.