Commonwealth Ombudsman Annual Report 2012—13 | Section 7

Section 7 Specialist and other roles

In addition to the Ombudsman’s role in investigating complaints about the administrative actions of Australian Government departments and agencies, we have a number of specialist oversight functions.

These include the following responsibilities:

- Defence Force Ombudsman: investigate complaints about the Australian Defence Force relating to or arising from present or past service

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman: oversee Australian Government law enforcement agencies, including joint responsibility for handling complaints about the Australian Federal Police (AFP) with AFP’s Professional Standards

- Immigration Ombudsman: investigate complaints, conduct visits to immigration detention facilities, and report to the Immigration Minister in relation to people who have been in immigration detention for two years or more

- Taxation Ombudsman: investigate complaints about the Australian Taxation Office

- Postal Industry Ombudsman: investigate complaints about Australia Post and other postal or courier operators that are registered as a Private Postal Operator

- Overseas Students Ombudsman: investigate complaints about problems that overseas students or intending overseas students may have with private education providers in Australia.

In addition to these specific specialist Ombudsman roles, our office also has the following functions:

- statutory responsibility for compliance auditing of the records of law enforcement and other enforcement agencies in relation to the use of covert powers

- a role as an active participant within the international community of Ombudsman organisations, with a focus on sharing experience in complaint handling and fostering good public administration within various countries in the Asia Pacific Region

- (over the past five years) oversight of the administration of programs for Indigenous communities under the Australian Government’s Northern Territory Emergency Response and Closing the Gap initiatives in the Northern Territory. Funding for this role has now ceased, but a focus on Indigenous programs remains one of our priorities.

- This chapter reports on these specialist Ombudsman roles (except for the Taxation Ombudsman, which is dealt with in Chapter 4), and other functions over the last year.

Defence Force Ombudsman

The office received 509 complaints about defence agencies compared with the 662 complaints in 2011–12, a decrease of 22%. ‘Defence agencies’ include the Australian Defence Force and cadets, the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, the Defence Housing Authority, as well as the Department of Defence (Defence).

Complaints from serving or former members of the Australian Defence Force are usually investigated by the Defence Force Ombudsman. Complaints typically involve Australian Defence Force employment matters, such as:

- pay and conditions

- entitlements and benefits

- promotions

- discharge

- delays involving the ‘redress of grievance’ processes or decisions by defence agencies regarding Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration claims.

Our office does not have jurisdiction over employment matters involving Australian Public Service employees working in Defence agencies.

Defence-related complaints from members of the public are usually investigated by the Commonwealth Ombudsman. Typically, these matters involve military aircraft noise, contracting matters and service delivery issues.

The office received 30 complaints about redress of grievance processes. Of the 27 matters considered, 24 involved delays. We do not consider redress of grievance complaints falling within the 180 day processing timeframe allowed by the Department of Defence.

On 26 November 2012 the Minister for Defence announced the establishment of the independent Defence Abuse Response Taskforce. This taskforce was given the role of assessing individual allegations of abuse in Defence that occurred before April 2011. During January and February 2013, 22 matters referred to this office by law firm DLA Piper during their Review of Allegations of Sexual and other Abuse in Defence were transferred (with the consent of the complainants) to the Defence Abuse Response Taskforce.

The Defence Force Ombudsman provided ongoing advice and input to an internal review of complaint handling processes initiated by the Department of Defence.

Throughout the year the Defence Force Ombudsman undertook some outreach and stakeholder engagement activities, including attending the Naval Cadets forum and presenting at the Air Force School of Administration and Logistics on the role of the Defence Force Ombudsman.

Postal Industry Ombudsman

Overview

One of the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s roles is to act as the Postal Industry Ombudsman (PIO). The PIO was established in 2006 to offer an ombudsman service for the postal and courier industry. Australia Post is a mandatory member of the scheme, while private postal operators (PPOs) can register voluntarily. At 30 June 2013 there were six PPOs active on the register.

The PIO can investigate complaints about postal or similar services provided by Australia Post or PPOs. While the PIO cannot investigate non-postal services, the Commonwealth Ombudsman can investigate non-postal services by Australia Post. Non-postal services by all other operators are out-of-jurisdiction.

Fees

The PIO was established with the intent to recover its costs from the industry by charging investigation fees. As foreshadowed in last year’s annual report, we conducted a review of how we charge for investigations conducted under the PIO scheme. We analysed investigations completed over a period of time to better ascertain the resources required to undertake investigations at different levels of complexity.

We determined that the fee levels were generally appropriate for the resources involved, with an adjustment to one fee level. There are four fee levels, which are based on the time and resources required to assess and investigate an approach.

As fees are calculated and applied retrospectively, the fees are determined after 30 June each year. The total fees invoiced in 2011–12 for the previous financial year were $403,550 which consisted of $399,732 for Australia Post, $2,031 for Australian air Express, and $1,787 for FedEx.

Restructure

As part of our office-wide restructure, we reorganised the PIO function to achieve a better balance between our operational and our strategic roles. We continued to assess and investigate individual approaches, but we were also able to focus more on issues of policy, process and systems that we identified through approaches, stakeholders, media and literature reviews.

‘Second chance’ transfer scheme

During the year we sought to improve our efficiency and effectiveness in resolving complaints. In conjunction with Australia Post, we developed a ‘second chance’ transfer scheme to operate between our two offices. Under the scheme, we transferred certain complaints directly to Australia Post to give it a second chance to resolve the complaint before we considered any further involvement.

These complaints were typically straightforward matters where we assessed whether a better outcome or explanation could have been provided by Australia Post. Complaints transferred under this scheme were not counted as investigations. In the event that the complainant returns to our office with the complaint unresolved, we would generally investigate. We have not extended the scheme to PPOs due to the relatively low number of approaches we receive about them.

Complaint trends

In 2012–13 we received 3,652 complaints about Australia Post, of which 353 (9.7%) were in the Commonwealth jurisdiction and 3,299 (90.3%) were in the PIO jurisdiction. Complaints about Australia Post represented 20% of the total approaches received by our office.

We received 15 complaints about other postal operators in the PIO jurisdiction, of which six were about Australian air Express and nine were about FedEx, making a total of 3,314 approaches in the PIO jurisdiction.

Of the approaches we received about Australia Post, we declined to investigate 3,277 (89.7%). Of those, we transferred 95 directly to Australia Post under the ‘second chance’ transfer scheme. Eleven of these returned to our office, and we investigated three of them.

The most common reasons for declining to investigate a complaint were that:

- the complainant had not yet made a reasonable attempt to resolve the issue with the agency, or had insufficient evidence of doing so

- we assessed that Australia Post should consider providing a better outcome and transferred the complaint to it under the ‘second chance’ scheme

- Australia Post or the PPO had provided a reasonable remedy or the remedy required under its terms and conditions of service

- a better practical outcome was unlikely.

We completed 440 investigations. The investigations were about Australia Post (439) and FedEx (one). We did not investigate any approaches about Australian air Express.

The time taken to complete an investigation varied according to the nature and complexity of the complaint, and the resourcing available in our office and PPOs at the time. We finalised 13% of Australia Post investigations within one month, and 71% within three months.

The total number of postal complaints received was significantly lower than in the previous financial year, but higher than the financial year before (see Table 7.2). As external factors drive the number of complaints we receive, it can be difficult to accurately pinpoint the reasons for variations. Australia Post has advised that the satisfaction rating from surveyed customers for its customer contact centre improved in the same period, following significant investment in its complaint management systems and staff training. The decrease in our complaints may reflect improvement in Australia Post’s complaint management.

The number of complaints has increased each year since 2006–07, peaking in 2011–12 (see Table 7.2). The decrease in completed investigations is due, in part, to us setting a higher threshold for investigation, with a stricter interpretation of whether Australia Post has met its obligations and whether we are likely to achieve a better outcome for the complainant. We allocate our resources in this way in order to achieve a better balance between our operational and strategic roles, whereby we can focus more on systemic issues.

Table 7.2: Complaint trends 2006 – 07 to 2012–13

Year | Australia Post approaches received | Private postal operators approaches received | Total approaches received | Completed investigations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2012–13 | 3,652 | 15 | 3,667 | 440 |

2011–12 | 4,137 | 36 | 4,173 | 486 |

2010–11 | 3,123 | 20 | 3,143 | 513 |

2009–10 | 2,626 | 11 | 2,637 | 557 |

2008–09 | 2,219 | 13 | 2,232 | 648 |

2007–08 | 2,083 | 4 | 2,087 | 745 |

2006–07 | 1,819 | 1 | 1,820 | 706 |

Complaint themes

The most common complaint themes were:

- single-event mail issues—including damage or loss of mail items, the failure of a mail hold or redirection, and problems with the method of delivery, where these issues were one off or occasional

- recurrent mail issues—where problems recurred despite repeated complaints to the postal operator

- customer contact centre-related—where Australia Post’s customer contact centre received, investigated and responded to complaints. Complaints were commonly about delays or a lack of response, the quality of information provided, and the remedy or compensation offered.

While the issues remained the same as these in recent years, their relative prevalence changed this year. In 2011–12 recurrent mail issues were the most prevalent, followed by customer contact centre issues. The lower prevalence of recurrent mail issues this year may reflect more effective action by Australia Post in resolving issues, while the lower prevalence of customer contact centre issues suggests improvement in Australia Post’s complaint management.

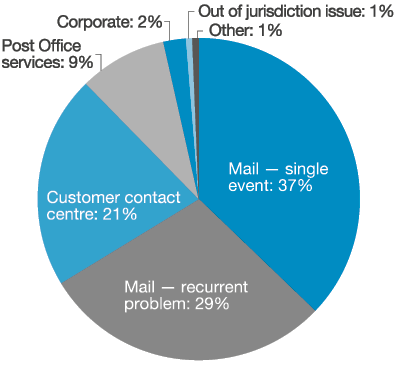

Figure 7.1: Australia Post complaint themes 2012–13

This figure shows Australia Post complaint themes for 2012–13. The percentages of complaints about each theme are: single mail events 37%; recurrent mail problems 29%; customer contact centre complaints 21%; Post Office services 9%; corporate related complaints 2%; out of jurisdiction complaints 1% and other complaints issues 1%.

Law Enforcement Ombudsman

When performing functions in relation to the Australian Federal Police (AFP), the Ombudsman may also be called the Law Enforcement Ombudsman. The Ombudsman has a comprehensive role in overseeing the AFP which includes:

- handling complaints about the AFP

- receiving mandatory notifications from the AFP regarding complaints about serious misconduct involving AFP members, under the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (the AFP Act)

- reviewing how the AFP handles its own complaints under Part V of the AFP Act (referred to as ‘Part V reviews’).

Part V reviews

Part V of the AFP Act details how the AFP must deal with complaints made about its members. This forms the basis of the AFP’s complaint management processes.

The AFP Act also requires the Ombudsman to review the AFP’s administration of Part V at least once each financial year, and to report the result of the reviews to the Parliament. When conducting our reviews, we consider matters such as whether:

- communication with complainants was reasonable

- complaint investigations were reasonably conducted

- complaint outcomes were reasonable.

In November 2012 we tabled a report in the Parliament on our activities under Part V of the AFP Act. This report is available on our website.

Stakeholder engagement and outreach and education activities

Our relationship with the AFP is cooperative and constructive. In 2012–13 we engaged regularly with the AFP to ensure a common understanding of the AFP’s processes and the purpose of our oversight function. For example, the AFP regularly invited us to provide comments on relevant policies and procedures.

We also presented to new members of the AFP’s complaint handling area the various ways in which we oversee the AFP, including our complaint, Part V review, and other inspection functions.

Inspections

Independent oversight process

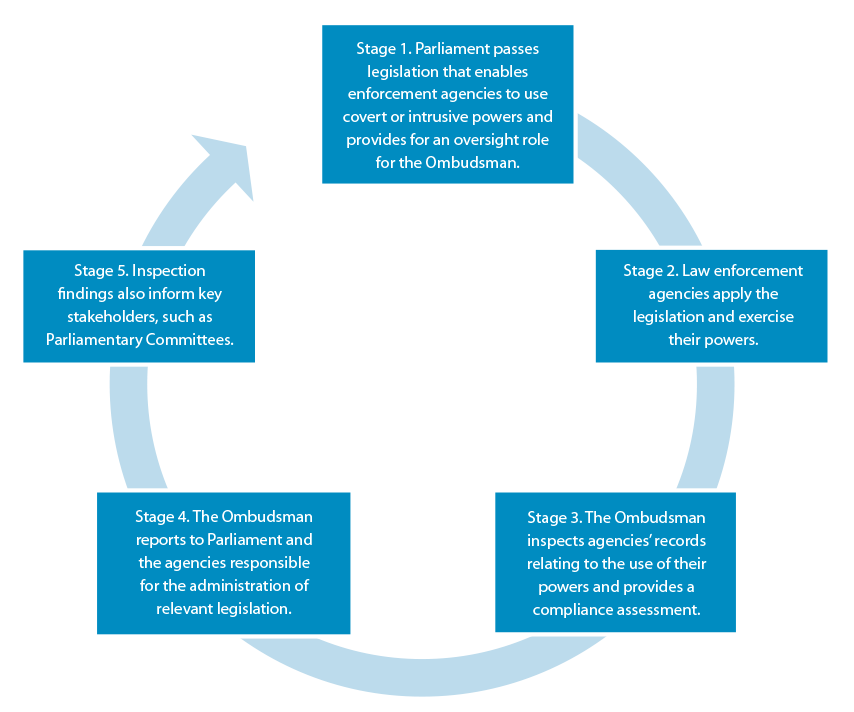

Our law enforcement inspections role and follow-up agency engagement and feedback provide an integrated five-stage approach to independent oversight.

The independent oversight process

Stage 1

The purpose of an independent oversight mechanism is to increase accountability and transparency of enforcement agencies’ use of covert and intrusive powers. As an oversight mechanism, the Ombudsman is required by law to inspect the records of certain agencies in relation to their use of covert and intrusive powers, which include:

- telecommunications interceptions by the Australian Federal Police (AFP), the Australian Crime Commission (ACC) and the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI)

- access to stored communications by Australian Government agencies, including the AFP, the ACC, the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service, and state and territory law enforcement agencies

- use of surveillance devices by the AFP, the ACC, the ACLEI, and state and territory law enforcement agencies under the Commonwealth legislation

- controlled operations conducted by the AFP, the ACC and the ACLEI.

During 2012–13 we also conducted a review of Fair Work Building and Construction’s use of its coercive examination powers.

Stage 2

When law enforcement agencies exercise their powers, they are required to keep records of their related activities, including any use or communication of information obtained through such activities. We then inspect these records to determine agencies’ compliance with their legislative obligations.

Stage 3

In 2012–13 we conducted 39 inspections, at both Commonwealth and state/territory levels. As well as inspecting agencies’ records to make a compliance assessment, we aimed to help agencies improve their processes to comply with the various legislative provisions. This included liaising with agencies outside of inspections and communicating shared issues to relevant stakeholders, as well as providing advice on best practices.

Agencies also use our inspection findings to encourage review and positive change. For example, in 2012 the AFP undertook a review of its administration of controlled operations, examining existing processes and looking for ways to improve compliance with legislation. As a part of this review, the AFP advised that it took into account our inspection findings, suggestions and recommendations.

Stage 4

In addition to reporting to the agencies on our inspection findings, we are required to report regularly to the Attorney-General and the Minister for Home Affairs. These findings may also form the basis of our annual briefings to relevant parliamentary joint committees.

We also provide feedback to the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department, the department responsible for administering the regimes we inspect, on how law enforcement agencies interpret and apply the provisions of different Acts, and any identified high-level systemic problems and issues.

For example, as a result of our inspections, we identified an ambiguity in the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 that makes it difficult for us to determine whether or not stored communications warrants were validly executed. In our view, the legislation requires clarification. This issue was reported in the Attorney-General’s Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 – annual report for the year ending 30 June 2012.

Stage 5

As well as meeting our statutory reporting requirements, we also aim to provide useful information to key stakeholders resulting from our inspection functions. For example, during 2012–13, we made a submission to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security about its Inquiry into Potential Reforms to National Security Legislation. Our submission is available on the committee’s website.

Improving our business practice

A key focus in 2012–13 for our inspection role was to improve the way in which we communicate compliance issues to agencies, to help them better comply with legislation and to improve our working relationships with agency stakeholders. We did this by ensuring consistency in how we communicated inspection findings, providing comments on agencies’ internal procedures and policies, and meeting with agencies outside of inspections.

This year we also enhanced our sampling methodology regarding how we choose which records to inspect. This, combined with an increase in agency use of certain legislative powers, resulted in us inspecting more records in 2012–13 compared to 2011–12.

Informing the public and decision makers

In addition to the submissions we made to parliamentary inquiries, during 2012–13 we published four reports and submitted 18 reports to the Attorney-General and the Minister for Home Affairs. Our published reports are a key element in enhancing accountability and transparency of enforcement agencies’ use of covert, intrusive or coercive powers. These reports also provide transparency on how we conduct inspections.

Our published reports generally provide an outline of our inspection methodology and criteria, our findings against each criterion, and any agency responses to our findings. In 2012–13, the Ombudsman released the following reports:

- September 2012: Biannual report to the Attorney-General on the results of inspections of records under section 55 of the Surveillance Devices Act 2004

- September 2012: Annual Report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s activities in monitoring controlled operations conducted by the Australian Crime Commission and the Australian Federal Police in 2011–12

- November 2012: Annual Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under section 54A(6) of the Fair Work (Building Industry) Act 2012

- March 2013: Report to the Attorney-General on the results of inspections of records under section 55 of the Surveillance Devices Act 2004.

The Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 does not permit the Ombudsman to publish reports on the results of telecommunications interceptions and stored communications access inspections. Instead, we provide information to the Attorney-General’s Department for inclusion in their annual report to the Parliament under this Act.

Immigration Ombudsman

The Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) operates an extensive network of immigration detention facilities nationwide. This network accommodates a large number of people from a wide variety of cultures in disparate locations. Our office has an important role in relation to the oversight of immigration detention facilities.

We carry out this role through:

- our immigration detention inspection program

- detention reviews under section 468O of the Migration Act 1958 (the Act)

- investigation of complaints about DIAC and its service providers by detainees or on behalf of detainees.

The number of people in immigration detention continues to be high by historical standards, as people continue to arrive in Australia as unauthorised maritime arrivals. We remain concerned about the disparity between the pre- and post-13 August 2012 unauthorised maritime arrival cohorts. Those who arrived before 13 August 2012 continue to be processed in accordance with the single statutory Protection Visa process while those who have arrived post-13 August 2012 are subject to the ‘no advantage principle’ and until recently had yet to have the processing of their claims for protection commence. (From 1 July 2013 DIAC has progressively referred post-13 August arrivals for application assistance to enable their claims for protection to be assessed.)

It is positive to note the decrease in the average duration of immigration detention. Both unauthorised maritime arrival cohorts have benefited from the use of Bridging Visas to move people out of immigration detention and into the community once they have been screened-in. The average time people are held in detention in 2012–13 was about 92 days compared with 205 days in 2011–12.

Immigration detention inspections program

The inspections visit program is a core part of our detention oversight function. We aim to visit each facility in the immigration detention network at least twice each year. These visits provide an opportunity to:

- engage with detainees through group and individual meetings

- record any complaints detainees may have

- provide information sessions about the role of our office to staff and detainees

- interview people detained for more than two years

- inspect the facilities and amenities

- assess the administrative functions undertaken within the facilities

- discuss operational issues with DIAC and its service providers.

Where the visits coincide with either a Client Consultative Committee or Community Consultative Group/Committee meetings, we may attend as observers. Attendance at these meetings provides insight into issues of relevance to the detainees and the local community.

During 2012–13 our teams visited the detention centres listed in Table 7.1.

Following each inspection visit, we provided DIAC with our key concerns, observations and suggestions arising from the visit. See Chapter 4 for a summary of these observations.

Table 7.1: Immigration detention facilities visited in 2012–13

Immigration Detention Facility | Location | Timing |

|---|---|---|

*Visit in relation to conducting interviews with long-term (two years or more) detainees only | ||

Adelaide Immigration Transit Accommodation | Adelaide SA | June 13 |

Berrimah House Immigration Residential Housing | Darwin NT | July 12 March 13 |

Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation | Brisbane QLD | March 13 |

Construction Camp Alternative Place of Detention | Christmas Island | November 12 April 13 |

Curtin Immigration Detention Centre and Alternative Place of Detention | Derby WA | June 13 |

Darwin Airport Lodge Alternative Place of Detention | Darwin NT | July 12 March 13 |

Inverbrackie Alternative Place of Detention | Woodside SA | June 13 |

Leonora Alternative Place of Detention | Leonora WA | June 13 |

Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre | Melbourne VIC | November 12* April 13 |

Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation | Melbourne VIC | November 12* April 13 |

Northern Immigration Detention Centre | Darwin NT | July 12 March 13 |

North West Point Immigration Detention Centre | Christmas Island | November 12 April 13 |

Perth Immigration Detention Centre | Perth WA | April 13 |

Perth Immigration Residential Housing | Perth WA | April 13 |

Pontville Alternative Place of Detention | Pontville TAS | June 13 |

Port Augusta Immigration Residential Housing | Port Augusta SA | May 13 |

Regional Processing Reception Point | Cocos (Keeling) Island | November 12 |

Scherger Immigration Detention Centre | Weipa QLD | June 13 |

Sydney Immigration Residential Housing | Sydney NSW | August 13* December 13* May 13* |

Villawood Immigration Detention Centre | Sydney NSW | August 13* December 13* May 13* |

Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre | Northam WA | April 13 |

Detention reviews

Statutory reporting

After a person has been in immigration detention for a period of two years, and every six months thereafter, the Secretary of DIAC must give the Ombudsman a report, under section 486N of the Migration Act, relating to the circumstances of the person’s detention. Section 486O of the Migration Act then requires the Ombudsman to give the Minister an assessment of the appropriateness of the arrangements for that person’s detention. The Minister tables the de-identified reports in Parliament together with their response. Post the ministerial response the de-identified reports are published on the Ombudsman’s website.

Two-year review reports

In 2012–13 the number of two-year detention reports received from DIAC increased over the previous year: 1,118 reports in 2012–13 compared to 683 in 2011–12. Of the 1,118 reports, 417 were first reports of people who reached 24 months in immigration detention, and 701 were subsequent reports for people who had been in detention for 30 months or longer.

Many of the people subject to these reports were released on Bridging or Protection Visas, removed from Australia, detained in correctional centres or transferred to community detention. The Ombudsman is still required to report to the Minister even if the person has been released from detention since DIAC provided the section 486N report.

The Ombudsman provided 674 reports to the Minister in 2012–13 compared to 130 the previous year. The high number of cases the Ombudsman is required to assess contin7ues to place considerable strain on the ability of our office to report to the Minister in a timely manner.

A review was conducted in 2012 of the format of the reports sent to the Minister with a view to streamlining processes and introducing abridged reports where no recommendations or assessments were made. A revised triage approach was implemented to support this approach. All cases received thorough consideration and the format of the report to the Minister was informed by the issues raised by the cases and the recommendations made by the Ombudsman.

The people who may be the subject of an abridged report include those who:

- are in criminal custody

- have been removed from Australia

- have been released on Bridging or Protection Visas

- in some cases, are in community detention.

Reporting on such cases in an abridged format allows the Ombudsman to focus resources on individuals whose circumstances require a more comprehensive summary of their detention arrangements.

Trends and issues raised in the two-year reports include:

- the deterioration in mental health of a significant proportion of people in closed detention facilities, including diagnosed conditions of schizophrenia or psychosis

- the importance of DIAC and its service providers working together to ensure they meet their duty of care obligations in relation to detainees

- in most cases, the alleviation of mental health concerns once the person was transferred to a less restrictive environment, such as community detention or a Bridging Visa

- the continued long-term detention (in some cases over four years) of all but one of the group of people who have been found to be owed protection but who have received an adverse security clearance from the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation.

Reports

Suicide and self-harm in the immigration detention network

The Ombudsman released a report under section 15 of the Ombudsman Act in May 2013. This report is discussed in Chapter 4.

Taxation Ombudsman

The Taxation Ombudsman role was created at the suggestion of the Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit (JCPAA) with the Commissioner of Taxation in 1995, in recognition of the unequal position between the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) and taxpayers. The role helps to focus attention on complaints about the ATO. The Taxation Ombudsman appears at the annual hearings of the JCPAA and provides a review of the ATO’s performance based on the complaints this office receives and our liaison activities with the ATO.

In 2012–13 we received 1,795 complaints about the ATO. These are discussed in detail in Chapter 4, Agencies Overview.

Australia Post

Most of the postal complaints we received were about Australia Post. Australia Post is a government business enterprise and operates under legislation (the Australian Postal Corporation Act 1989) that establishes three types of obligations: commercial, community, and general governmental. Some of its obligations are to:

- perform its functions in a manner consistent with sound commercial practice

- supply a reasonably accessible ordinary letters service at a single uniform rate

- ensure that the performance standards for the letter service reasonably meet the social, industrial and commercial needs of the community.

In setting financial targets, the Board of Australia Post must have regard to a range of matters, including the expectation that Australia Post will pay a reasonable dividend to the government.

Australia Post has the exclusive right to operate the letters service. Its other services, including parcels, operate in competition with other providers in the market.

We consider these factors when assessing and investigating approaches. We also try to help complainants better understand these obligations, as Australia Post’s customers are often unaware of them or dispute their validity.

From complaints and investigations, we identified some issues with Australia Post’s information, policies and procedures. We considered that addressing these might help Australia Post’s customers better understand their rights and obligations, and might enable better outcomes for complainants.

Accessibility and quality of information

Information provided by Australia Post to its customers includes the terms and conditions for its services, post guides, web pages, and extracts of these on some postal products.

This information should help its customers choose the service best suited to them, particularly with regard to the delivery timeframe, the security of the item, the compensation payable, and the level of risk involved. When responding to complaints and determining compensation, Australia Post generally considers whether the customer and Australia Post have each met the conditions set out in this information. We consider it vital that Australia Post ensures the information is accessible, correct and clear.

We suggested to Australia Post that the following information could be improved:

- ‘deliver as addressed policy’ — there is a potential conflict with terms and conditions that enable mail to be returned to the sender if Australia Post knows the addressee is not receiving mail at the address

- website content indicating that Registered Post included tracking and, conversely, that tracking was not included

- the role of packaging in assessing a compensation claim for damage

- the International Post Guide — clarification and consistency on who has the right to claim compensation for damage and loss in the different postal services

- terms and conditions – potential conflict with the Parcel Post Guide regarding compensation payable for coins damaged or lost in the post.

Australia Post undertook to review this public information. Some changes were made during the year, while others are being considered as part of Australia Post’s revision of its terms and conditions and post guides which is expected to be completed by October 2013.

In response to our investigations, Australia Post revised some of the internal information used by agents in its customer contact centre. This included information on managing complaints about disputed delivery signatures and about disputed mail redirections.

Policy and procedures

We identified a number of recurring issues that had the potential to create significant problems and result in an unreasonable outcome for the complainant. Following our investigations and feedback, Australia Post made a number of changes, two of which are described below.

Disputed delivery signatures

We received a number of complaints involving disputed delivery signatures. We questioned whether the arrangements for investigating the issue were effective or reasonable. At the time, if an addressee made a complaint to Australia Post about non-delivery of an item requiring a delivery signature, Australia Post would generally direct the addressee to the sender. If the sender then made a complaint and Australia Post found a signature on record, the sender or Australia Post might decline to take further action. Alternatively, Australia Post might investigate, but with little effect given the lapse of time.

As a result of our involvement, Australia Post changed their complaint-handling arrangements. Agents in its customer contact centre should now immediately log a complaint, investigate with the relevant delivery facility, and compare the addressee’s signature with the one on record. If the signatures do not match, Australia Post should consider the item as undelivered, show this in the record, and determine any compensation claim accordingly.

Unauthorised mail redirections

We received complaints about unauthorised mail redirections whereby the complainant had found that somebody else had arranged for Australia Post to redirect the complainant’s mail to another address without consent. At the time, Australia Post would generally contact the applicant to confirm their authority. If the applicant confirmed it, Australia Post would refer the complainant back to the redirection applicant to resolve the matter.

We questioned whether relying on the applicant was effective or reasonable, and whether Australia Post should consider alternative action, given the application form’s warning that redirecting mail without authorisation is a criminal offence.

As a result of our involvement, Australia Post undertook to revise the complaint-handling advice to agents in its customer contact centre, so that it is clear about escalating complaints to its Security Investigation Group which, in turn, may involve the police.

Forecast

We expect broad complaint themes to remain largely the same, although we expect a greater number of complaints about the tracking service for all domestic parcels, compensation for lost ordinary parcels, and possibly parcel delivery (attempted delivery versus automatic carding).

We will continue to monitor complaint themes to identify potential issues in Australia Post’s policies, processes and systems, and to pursue these with Australia Post through meetings, correspondence, issues papers or formal reports.

We will review the complaint outcomes of the direct transfer ‘second chance’ scheme. We want to identify how many complainants return to us, on which issues, and why, with a view to informing Australia Post so that it can consider how to better address the issues.

We expect that changes in Australia Post’s performance and complaint management will help improve its complaint handing, and reduce the number of complainants contacting our office. Australia Post advised us that its initiatives include:

- new and expanded systems to monitor and record deliveries

- new and ongoing programs to train its customer contact centre agents, and new technology to enable supervisors and managers to identify shortfalls in performance

- improved technology systems to better integrate information about complainants and their current and past complaints, and between different business lines within Australia Post.

We will continue to provide feedback to Australia Post at the operational and corporate levels, with a view to helping it improve its systems and resolve some of the underlying causes of complaints. We will also continue to seek better outcomes for complainants, where warranted.

Overseas Students Ombudsman

The Overseas Students Ombudsman operates within the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman as a statutorily independent external complaints body for overseas students complaining about the actions or decisions of a private registered education provider.

The Overseas Students Ombudsman has three clear roles under section 19ZJ of the Ombudsman Act 1976 legislation:

- investigate individual complaints

- report on trends and systemic issues in the sector

- work with providers to promote best practice complaint handling.

Since commencing in April 2011, the Overseas Students Ombudsman has received more than 1,000 complaints from overseas students relating to about one quarter of the more than 900 private registered providers in our jurisdiction. This includes every state and territory (except South Australia, where the Training Advocate has jurisdiction).

In investigating individual complaints, the Overseas Students Ombudsman focuses on achieving practical remedies where a student has been adversely affected by a provider’s incorrect actions. We also uphold complaints in support of the provider where the provider has followed the Education Services for Overseas Students Act 2000, the National Code of Practice for Registration Authorities and Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students 2007 (National Code) and its own policies and procedures. In other cases, we help both parties come to a resolution where there are problems on both sides.

Complaint themes

In 2012–13 we received a total of 442 complaints about private registered education providers in connection with overseas students. We started 189 complaint investigations and closed 447 complaints (including some complaints received in the previous financial year). Of the complaints received during the year, 258 were not investigated because:

- the student had not yet exhausted their provider’s internal complaints and appeals process

- we transferred the complaint to another complaint-handling body better placed to deal with the issue

- an investigation was not warranted in all the circumstances, for example, we were able to form a view on the basis of the documents provided by the student without the need to contact the provider.

The top three types of complaints the Overseas Students Ombudsman received about private registered providers concerned:

- providers’ decisions to report students to the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC) for failing to meet attendance requirements under Standard 11 of the National Code (112 students)

- providers’ decisions to refuse a student transfer to another provider under Standard 7 (92 students), and

- disputes about a student’s entitlement to a refund of pre-paid tuition fees (90 students).

Other complaints of significant proportion were fee disputes (32 students); decisions of providers to report students to DIAC for failing to meet course progress requirements under Standard 10 of the National Code (25 students); disciplinary reasons or non-payment of fees (12 students); and provider decisions to refuse deferral requests (11 students).

Most providers have willingly assisted our investigations by providing the information requested in a timely manner. We did not need to use our formal powers under section 9 of the Ombudsman Act 1976 to compel a provider to produce documents or answer questions in 2012–13.

Under section 19ZK, the Overseas Students Ombudsman must transfer a complaint to another statutory office holder if the complaint can be more effectively dealt with by that alternative complaint handling body. In 2012–13 we transferred 22 complaints to the Australian Skills Quality Authority relating to the quality or registration of a course, and one complaint about discrimination to the Australian Human Rights Commission. We transferred 14 complaints to the Tuition Protection Service, including four complaints about provider closures and eight complaints about providers not paying refunds on time, after a student withdrew or had their Student Visa application refused.

We transfer refund complaints to the Tuition Protection Service where the student is clearly eligible for a refund. However, the Overseas Students Ombudsman investigates more complex refund complaints, where it is not clear whether the student is owed a refund or how much should be refunded. We also consider complaints that fall outside the jurisdiction of the Tuition Protection Service, for example, where it has been more than 12 months since the default date, in which case the Tuition Protection Service is precluded from considering the matter, but the Overseas Students Ombudsman has power to investigate.

Trends and systemic Issues

Overseas student complaint statistics

In 2012–13 the Overseas Students Ombudsman published quarterly statistics on our website at www.oso.gov.au showing the number of complaints received about a range of issues. This information will allow the identification of trends in complaint issues over time.

The Overseas Students Ombudsman is also working with the state and territory Ombudsman offices and the South Australian Training Advocate to explore ways to generate overseas student complaint statistics which can be compared across jurisdictions. The Overseas Student Ombudsman is taking the lead on this ongoing project.

Systemic issues

The Overseas Students Ombudsman did not undertake any ‘own motion’ investigations during 2012–13. We have, however, prepared an issues paper highlighting problems we have noted with a small number of private providers receiving Overseas Students Health Cover payments from overseas students but then failing to pass this money on to the health insurance company. This action leaves students without health insurance and, consequently, places those students in breach of their visa conditions. The issues paper includes de-identified case studies and will be sent to a range of government agencies to generate discussion during the first quarter of 2013–14.

Other common problems noted during 2012–13 through our complaint investigations were highlighted in our first provider e-newsletter, in the article ‘Are you making any of these mistakes?’. This is available on the Overseas Student Ombudsman’s website at www.oso.gov.au/publications-and-media/.

Cross-agency issues

The Overseas Students Ombudsman liaises with a number of Australian Government agencies involved in international education policy and programs. We met with the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA), the Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency, DIAC and the Department of Innovation, Industry, Climate Change, Science, Research and Tertiary Education throughout 2012–13 to discuss issues related to overseas students and registered providers.

The Overseas Students Ombudsman has the power to report providers of concern to the national regulators, ASQA or the Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency.

In 2012–13 we used our power under section 35A of the Ombudsman Act 1976, to disclose information in the public interest, on eight occasions to disclose to ASQA details of complaints where it appeared to us that a private provider may have breached the Education Services for Overseas Students Act or the National Code, and we considered that it was in the public interest to advise the national regulator of the details. Once we provide this information to ASQA, it is up to ASQA to decide what regulatory action, if any, it should take.

We did not make any disclosures to the Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency in 2012–13. We did meet with them in 2012–13 to discuss information sharing arrangements, which will be confirmed in a memorandum of understanding, which they are currently developing.

In March 2013 we met with DIAC to discuss the abolition of automatic and mandatory cancellation of Student Visas, which came into effect on 13 April 2013. Previously, once a provider reported an overseas student to DIAC for poor attendance or course progress, their visa could be automatically cancelled without review by the Migration Review Tribunal.

It was also mandatory for DIAC to cancel the student’s visa if they had failed too many subjects or missed too many classes. DIAC also now has more discretion not to cancel the student’s visa if compelling and compassionate circumstances apply. We met with DIAC and clarified that the student’s right to lodge an external appeal with the Overseas Students Ombudsman, objecting to their provider’s intention to report them to DIAC, remains unchanged. The Overseas Students Ombudsman will continue to investigate to ensure that providers have followed the required processes before any reporting to DIAC.

Submissions

On 14 February 2013 we appeared before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Education and Employment. We made a verbal submission and participated in discussions relating to international education. We also provided further information that was supplementary to what we had previously supplied at the international education roundtable held on 3 April 2012. The committee tabled its report, International education support and collaboration, on 27 May 2013.

Stakeholder engagement and outreach

Promoting best practice complaint handling

The Overseas Students Ombudsman promotes best practice complaint handling, including through our Best practice complaints handling guide for education providers, to help private registered providers resolve complaints internally. This ensures problems can be dealt with directly by providers in a timely and effective manner, giving students a satisfactory resolution and contributing to a positive study experience in Australia. If complaints are mishandled, it can damage not only the reputation of the individual provider but the reputation of the Australian international education sector as a whole. To avoid these negative impacts, the Overseas Students Ombudsman works with providers to help them improve their internal complaints and appeals processes.

Provider newsletter

On 2 May 2013, we sent out the first Overseas Students Ombudsman provider e-newsletter directly to the Principal Executive Officers of more than 900 private registered education providers across Australia. The newsletter provides information on the Overseas Students Ombudsman’s role, promotes best practice complaint handling, and provides information to the sector on complaint issues and trends.

Student newsletter

A quarterly newsletter for overseas students is due to be sent out in the first quarter of 2013–14. It will include information, advice and tips for overseas students on their rights and obligations and how to deal with problems that may arise with their private registered education provider.

International education conferences

During the year staff from the Overseas Students Ombudsman attended a range of relevant international education conferences and policy briefings. They spoke to education providers, international students, government stakeholders and peak body representatives to promote the role of the Overseas Students

Ombudsman and discuss particular issues and challenges faced by international students and education providers.

In 2012–13 we attended the:

- Council of International Students Australia Conference on 10 July 2012

- Australian Council for Private Education and Training Conference on

30–31 August 2012 - English Australia Conference on 20 September 2012

- NSW Ombudsman University Complaint Handling forum in Sydney on 17 February 2013

- Australian Education International’s International Education Policy Briefing on 1 March 2013.

Government stakeholder liaison

In May 2013 the Overseas Students Ombudsman attended the Joint Committee on International Education, which is the primary forum for Commonwealth, state and territory government officials to collaborate on public policy and pursue common strategic directions in supporting the sustainability of international education in Australia.

In April and June 2013, the Overseas Students Ombudsman also attended the Inter-Departmental Forum, which brings together Australian Government officials from relevant departments to discuss international education matters.

Other complaint handling bodies

The Overseas Students Ombudsman also engaged with other complaint handling bodies to share information and expertise on handling overseas student complaints. This included meetings with the Western Australian International Education Conciliator on 22 March 2013 and the state and territory Ombudsman offices—together with the South Australian Training Advocate—on 23 May 2013.

Looking ahead

We will continue to engage with private providers, overseas students, peak bodies, relevant government departments and other complaint handling bodies. Key deliverables for the next year include developing an online best practice complaint handling training package for private providers and producing the first e-newsletter for overseas students.

International

Our office has been actively supporting Ombudsman organisations and allied integrity institutions in the Asia Pacific region over a number of years and, most recently, in Latin America. We do this through institutional partnerships and peer networks, and also by directly helping individual offices build their organisational capacity.

The aim of the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s international program is to foster more effective Ombudsman organisations. An effective ombudsman contributes to better public governance which in turn contributes to improving the lives of some of the world’s least advantaged communities.

Our programs are mostly funded by AusAID and we contribute senior staff time and expertise. Individual staff members are involved in the program through learning exchange placements, seminars and ongoing dialogue with our international colleagues. We benefit greatly from engaging with other Ombudsmen offices by sharing and sharpening our skills and ideas.

Pacific Ombudsman Alliance

Over the past four years our office has received funding from AusAID for the Pacific Ombudsman Alliance (POA), a strong regional network of Ombudsmen and allied institutions. This funding allows the POA to provide a broad range of support to its members.

Our four-year program was designed as a consolidation phase of the POA. Our aim was to build the existing association into a strong, mutually supportive network that helps POA members make real improvements to their effectiveness, resulting in better public administration in each country.

At the end of this phase, the POA has been able to reflect on significant successes in individual countries, and across the organisation as a whole. It has developed into a flexible, responsive and practical organisation able to use Australian aid money sensibly to address immediate identified need.

As well as providing technical support, the combined expertise of the POA membership has been a tremendous asset, as members have many decades of experience as Ombudsmen and senior public officials. Sharing common problems and solutions with peers has been a significant part of the POA’s success.

This success was confirmed by an independent report, commissioned by AusAID, to evaluate the POA’s efficiency and effectiveness. The report is due to be finalised in July 2013, but the draft findings are that the POA is providing a valuable function for strengthening Ombudsman offices and for improving governance in the Pacific. The Review Team recommended that AusAID and the New Zealand Government continue to provide support to the POA.

A significant challenge for many POA members this year has been vacancies or delays in substantive appointments of an Ombudsman. This hole in leadership creates practical difficulties for the effective functioning of member offices, and weakens the integrity framework in that country. The POA has been able to provide advice for Ombudsman staff during this time, and encouraged governments to appoint new Ombudsmen efficiently and be proactive in planning for succession.

A highlight of 2012–13 was our members’ meeting, held in conjunction with the International Ombudsman Institute general conference, in Wellington, New Zealand, in November 2012. There is more information about this later in this section.

Following are some highlights of the activities the POA has funded and organised in the past 12 months:

- The Solomon Islands Leadership Code Commission hosted a legal officer from the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office on a four-week placement in September – October 2012. The placement supported the office with key legislative reforms, general legal advice and improving internal case management procedures. This support has helped the office to progress a number of high-profile misconduct charges in 2013.

- The Office of the Ombudsman of Samoa hosted a delegation from the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office in December 2012 to deliver corporate training and review the outcomes of the long-term support provided by the POA. The delegation found that long-term support by the POA has created sustainable change and contributed to a revitalisation of the office. The office has released a number of important high-profile reports and is experiencing a significant increase in public contact, largely as a result of a successful public outreach program. The office will also take on the function of National Human Rights Institute from July 2013.

- The POA facilitated a Leadership Workshop in Niue in November 2012, together with the Commonwealth Pacific Governance Facility of the Commonwealth Secretariat. The workshop was held over several days and brought together members of the Niue Legislative Assembly, senior officials and key members of the Niue community. The workshop produced a set of good leadership values and ethical standards for Niue leaders, and options for their adoption and enforcement.

- The Auditor-General of the Republic of the Marshall Islands hosted a senior investigator from the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office on two long-term placements aimed at improving the efficiency of investigations, asset recovery and prosecutions. The placement has led to the development of a sophisticated investigations manual and a review of the office’s internal processes and legislative mandate.

- The newly appointed Vanuatu Ombudsman and Cook Islands Ombudsman visited Sydney and Canberra on a one-week induction visit hosted by the Commonwealth and New South Wales Ombudsmen. This visit covered a broad range of Ombudsman functions and introduced the two new Ombudsmen to both offices.

- The New South Wales Ombudsman has sent one of its senior investigators on a POA placement to the Vanuatu Ombudsman’s Office, providing support for legislative reform, assessing options for a case tracking system, and identifying ways to improve the corporate support functioning of the office.

- The Acting Commissioner for Public Relations in Tonga spent three weeks with the New Zealand Ombudsman’s Office to learn about his new role (a complaint-handling body with a role similar to that of an Ombudsman).

- The Public Service Office in Kiribati is a POA member, with a non-legislative responsibility for accepting and resolving complaints from members of the public. The New South Wales Ombudsman’s Office sent a senior investigator to the Public Service Office to help them identify how the roles and functions of an Ombudsman could be performed within the existing structures in Kiribati.

Dialogue between Pacific Ombudsmen

The POA held its fourth annual members meeting in Wellington, New Zealand, on 10 November 2012. The meeting brought together member organisations from 14 Ombudsman offices and allied Institutions to strengthen regional cooperation and share strategies for promoting good governance in the Pacific. The meeting was held in the spirit of warm professional collegiality and the discussions highlighted a great number of achievements and positive work being done in member organisations—in many cases with the support of the POA.

During the meeting the members elected a new Board, with the Australian Commonwealth Ombudsman, Colin Neave, nominated as the Chair. Members also took the opportunity to discuss and agree on the strategic direction of the POA, and participate in a review of donor funding coordinated by AusAID. The feedback from the members supported the review’s finding that the POA is providing a valuable function for strengthening Ombudsman offices and for improving governance in the Pacific.

The International Ombudsman Institute’s World Conference was also held in Wellington in the week following the POA meeting, and a number of POA members stayed on to attend. The theme of the conference was ‘Speaking truth to power’, drawing together some of the world’s most prominent and highly regarded Ombudsmen and integrity professionals. The conference sessions focused on key issues for accountability agencies in the 21st century, including delivering more with less, serving vulnerable populations effectively, securing resources, and developing innovative practices.

The conference was notable for passing a change in the International Ombudsman Institute’s by-laws that should ensure that the institute retains its relevance as Ombudsman offices around the world gain additional functions and responsibilities. One of the highlights of the conference was developing linkages with the dynamic and engaging Ombudsman of the Caribbean. In a meeting of the Pacific and Caribbean Ombudsmen, they discussed shared experiences in serving similarly small and poorly resourced nations and innovations for improving the effectiveness of their respective offices.

The conference proved an ideal opportunity for the host office, the New Zealand Office of the Ombudsman, to highlight the magnificent environment and culture of New Zealand. Highlights included the Powhiri, the Maori ceremonial welcome, and the Poroporaki, the conference closing.

Twinning program with Papua New Guinea

Our office has had a twinning program, supported by AusAID, with the Ombudsman Commission of Papua New Guinea (PNG) since 2006. Twinning is a method of aid delivery that uses a long-term equal partnership to create strong links between individuals, teams and organisations. The program benefits participating individual employees, but it also supports organisational reform.

Activities for each year’s program are decided at the end of the previous year as part of both organisations’ strategic planning. This year, our program expanded to include the Leadership Division of the Ombudsman Commission of PNG. This division has responsibility for investigating breaches of PNG’s Leadership Code, and referring suspected breaches to the Public Prosecutor for prosecution.

L–R Phoebe Sangetari, Ombudsman from the Ombudsman Commission of PNG, and Beverley Wakem, Chief Ombudsman of New Zealand, at the Pacific Ombudsman Alliance Annual Conference in Wellington New Zealand, November 2012.

The cornerstone of the program is reciprocal placements of individual officers. In the past 12 months, the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s Office has hosted three Ombudsman Commission of PNG investigators on placement in the Canberra and Adelaide offices. During their placement, the officers also visited other Commonwealth and state agencies, including the Victorian Ombudsman’s Office, the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department, and the Australian Transaction Reports and Analysis Centre (AUSTRAC).

A fourth Ombudsman Commission of PNG investigator, from the office’s Leadership Division, was placed with the Queensland Crime and Misconduct Commission to focus on misconduct investigations. The Commonwealth Ombudsman has sent two placement officers to the Ombudsman Commission of PNG: the first to help with setting up a toll-free complaint number, and the second to assist with policy development and legislative reform.

Providing support in Indonesia

The nine Ombudsmen of the Republic of Indonesia (ORI) are managing a rapidly growing organisation with a very broad responsibility for overseeing government in Indonesia.

As ORI nears its goal of opening 33 regional offices—one in each province—our office is providing assistance in training the new officers and supporting the Chief Ombudsman in his goal to place ORI at the forefront of improving government administration in Indonesia.

In January 2013 staff from the Commonwealth Ombudsman Office and the West Australian Ombudsman’s Office delivered a training program for new investigators in ORI’s regional offices. ORI has a legislative responsibility for supporting public sector complaint handling across all levels of Indonesian public service delivery. As part of this role, they have introduced unannounced inspection visits of government agencies that provide services to the public.

During a planning visit in Jakarta in April, our staff were able to accompany ORI staff on unannounced inspection visits to three government departments, and see first-hand the thorough and professional inspection process that ORI has introduced.

Our program in Indonesia is funded by AusAID, and is in partnership with the West Australian and New South Wales Ombudsmen. This partnership gives the program access to many skilled and expert staff.

Partnering with the Solomon Islands

In 2012 our office signed a memorandum of understanding with the Solomon Islands Ombudsman’s Office to formally mark our joint commitment to an institutional partnership. Funded by the Regional Assistance Mission to the Solomon Islands, the institutional partnership has facilitated flexible, timely and collegiate assistance to the Solomon Islands Ombudsman.

Through this partnership, our office is supporting the Solomon Islands Ombudsman Office in developing its Case Management System. This system is now fully operational, capturing data not previously recorded by the office. This data will greatly assist the office in monitoring its case load and producing accurate reports.

The Solomon Islands Ombudsman’s Office hosted one of the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s senior investigations officers on a short-term placement in June – July 2013. During this placement the officer worked closely with the staff to develop the office’s case management capability and align the Case Management System with standard operating procedures and processes.

We are also helping the Solomon Islands Ombudsman’s Office to update its information and communications technology infrastructure. Since May 2012, five support visits have been carried out by Commonwealth Ombudsman IT staff. The upgrade project included support to the Solomon Islands Leadership Code Commission, as they share the same building and information and communications technology infrastructure with the Ombudsman’s Office.

All technical work has now been completed by Commonwealth and Solomon Islands staff. Both the Leadership Code Commission and the Ombudsman’s Office are connected to the central government server and are operating on new SharePoint sites. The connection will ensure the two offices benefit from whole-of-government information and communications technology developments.

Institutional links with Peru

In 2011 we received funding from AusAID for a program to develop links with the Defensoria del Pueblo in Peru. The Defensoria has been established for 20 years and is highly regarded both in Peru and in the international Ombudsman community.

Following a two-week research project, a scoping team of three people visited the Defensoria in February 2012. The trip was very successful and a number of important personal and professional links were made between the offices.

In August 2012 a delegation of two officers from the Defensoria travelled to Australia for a week, visiting Canberra, Sydney, Parkes and Stockton Beach. The objective of the visit was to explore issues including native title, Indigenous land ownership, economic development by Indigenous communities, and building strong local relationships with the mining industry.

The delegation met with a number of organisations, including the NSW Aboriginal Land Council, the NSW Minerals Council, Reconciliation Australia, Rio Tinto staff at Northparkes, the Commonwealth Attorney-General’s Department, and the Office of the Coordinator-General of Remote Indigenous Services.

In April and May 2013, the Commonwealth Ombudsman participated in a meeting of the Federation of Ibero-American Ombudsmen in Lima, Peru, on the role of the Ombudsman in the Law of Prior Consultation. This law is a response to the International Labour Organization Convention 169 – Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, ratified by Peru on 2 February 1994.

Commonwealth Ombudsman Colin Neave and staff meet with representatives from the local indigenous communities, Cusco, Peru in May 2013

This provided a wonderful opportunity to meet many of the Ombudsmen from Latin America. The Commonwealth Ombudsman took the chance to forge ties with the Ombudsman of Bolivia, currently the head of the Andean Ombudsman Association. The delegation also travelled to Pucallpa in the Ucayali region, and Cusco in the Cusco region, and met with representatives from both Amazonian and Andean communities.

The program was completed in May 2013.

Norfolk Island Ombudsman

The Ombudsman Act 2012 (Norfolk Island) was passed by the Norfolk Island Legislative Assembly in July 2012. Section 29A of the Act, which came into operation on 24 August 2012, allows for the appointment of the Commonwealth Ombudsman as the Norfolk Island Ombudsman.

While we undertook preparatory work for the appointment in 2012, formalisation of the appointment as required under s 29A—and future funding arrangements for the Norfolk Island Ombudsman function—were not finalised by 30 June 2013.

On the understanding that the Ombudsman would be formally appointed, our office received four complaints in 2012–13. These complaints will be assessed when the appointment of the Ombudsman is finalised.

Public Interest Disclosure

On 26 June 2013 the Australian Parliament passed the Public Interest Disclosure Bill, legislation which establishes the first stand-alone whistleblower protection scheme for federal public servants, contractors and employees of contractors who report wrongdoing within the Australian Public Service. The Public Interest Disclosure Bill received Royal Assent from the Governor-General on 15 July 2013 and became law. The Public Interest Disclosure Scheme will come into operation no later than 16 January 2014, six months after Royal Assent. The Public Interest Disclosure Act (the PID Act) also includes a statutory review of its operations two years after commencement.

The roles envisaged for the Commonwealth Ombudsman under the PID Act will be key enablers in ensuring the legislation meets its objectives by:

- assisting agencies and disclosers

- raising awareness of the scheme

- providing oversight of agency decisions

- providing disclosers with greater certainty when making an external public interest disclosure

- enabling greater transparency and accountability by reporting to the Parliament on the operation of the scheme.

In particular, under the legislation the Ombudsman may set standards relating to:

- procedures, to be complied with by the principal officers of agencies, for dealing with internal disclosures

- the conduct of investigations under the PID Act

- the preparation of reports of investigations under the PID Act

- the provision of information and assistance and record keeping for the purposes of the Ombudsman’s annual reporting.

These standards establish obligations against which the Ombudsman can test the compliance of agencies. The standards will need to anticipate the wide cross-section of agencies that will be required to administer the PID Act and will be designed to avoid conflict with existing legislative and other established requirements.

The Ombudsman:

- is required to assist principal officers, authorised officers, public officials, former public officials and the Inspector-General Intelligence and Security in relation to the operation of the Act. The Ombudsman will perform this function by providing guidelines and fact sheets tailored to meet the needs of the different stakeholders. The Ombudsman will also provide a point of contact for the provision of more specific advice to agencies in the management of their obligations and those people who are thinking about making—or who have already made—a disclosure under the scheme

- is required to conduct education and awareness programs for agencies, public officials and former public officials in relation to the operation of the Act. The Ombudsman will perform this function through a range of initiatives, including fact sheets, guidelines and other promotional material, and providing face-to-face educational and promotion sessions where appropriate

- will be authorised to receive and investigate disclosures. While the intention is for the majority of investigations to be conducted by the agencies themselves into matters that arise within their organisation, if the matters are particularly complex or involve multiple agencies the Ombudsman (or another investigative agency) may become involved. When the Ombudsman does investigate, our office will bring to the task considerable expertise and all the powers under the Ombudsman Act 1976

- will take reports from agencies whenever a disclosure is allocated to an agency and whenever a decision is taken not to investigate a disclosure or to discontinue such an investigation. In addition to this, the Ombudsman will be required to determine extensions of time for the investigation of disclosures, providing a further safeguard against inaction and delay

- must provide to the Minister for tabling in the Parliament an annual report on the operation of the scheme. In order to give effect to this requirement, the Ombudsman will issue standards on the provision of information and assistance and record keeping by agencies.

During the year the Ombudsman’s Office was closely consulted by the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet as the key stakeholder in the development of legislation. The focus of these efforts was directed at achieving a scheme that ensured strong protections for whistleblowers and agency accountability, yet was overarching in concept, allowing existing processes and integrity arrangements to operate.

Our office also made significant headway in the development of standards, guidelines and other material in preparation for the commencement of the scheme. The PID scheme applies to the entire public sector (not just APS employees), including contractors, consultants, Defence, AFP and Parliamentary Service employees as well as former public officials. No definitive information is currently collected on the number of public interest disclosures that are currently raised within the Australian Government. This creates a high level of uncertainty in terms of the workload and effort that will be required to implement and oversee the scheme and generates considerable resourcing risk for the Ombudsman.

An effective public interest disclosure scheme provides indirect benefits to all Australians. It helps ensure the efficient, effective and ethical delivery of government services and, ultimately, helps reduce risks to the environment and health and safety of the community. It will instil citizen confidence in the Australian public sector.

A delegation from Peru’s Defensoria del Pueblo visiting the Northparkes mine site with officers from the Commonwealth Ombudsman’s office, August 2012.