Part 4 - What we do

Social Services agencies and programs

Case study

Ms W complained that Centrelink had raised a debt of over $1000 as a result of events 12 years earlier. The office investigated and established that there were three debts in total, the earliest of which was raised in 1997. The office established that Centrelink was legally entitled to recover the debts as it had taken action to recover them individually within six years of the date that it knew or ought to have known about each of them.

But while the office was satisfied that Ms W's debts were legally recoverable, the investigation discovered that the Department of Human Services's (DHS) internal procedures meant that action to recover one debt from a person had the effect of extending the time limit on all Centrelink debts the person owes.

After the office had discussed this with DHS and the Department of Social Services (DSS), both departments accepted the view that this procedure was unreasonable. Accordingly, they amended the procedure to make clear that action to recover a debt only extends the time limit for that particular debt.

This section of the report focuses on agencies that are responsible for government payments and services (such as DSS and the Department of Employment) and for the delivery of those services—in most cases, DHS.

It also discusses the office's oversight of programs specifically delivered to or for Indigenous people and people with disability, including the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

Department of Human Services

In 2015–16, complaints about DHS represented 49.8 per cent of all Commonwealth Government department related complaints received. Most of these were about DHS's Centrelink program (40.6 per cent). DHS complaints also increased across a number of programs in the previous year, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Complaint trends in DHS programs

| DHS program | Number of complaints in 2015–16 | Number of complaints in 2014–15 |

|---|---|---|

| Centrelink | 8702 38.6% increase | 6280 |

| Child Support | 1452 1.1% decrease | 1468 |

| Other DHS programs | 508 38% increase | 368 |

The office investigated seven per cent of those complaints and referred 52 per cent back to DHS because they had not already been raised with that agency.

In cases where the person is vulnerable or requires help to make a complaint, the office follows a process known as a 'warm transfer'. This means the complaint is passed directly to DHS on the understanding that the complainant may come back to us if the complaint has not been resolved within five working days. In 2015–16 the office referred 1152 cases back to DHS in this way.

DHS—Centrelink

Centrelink operates on a large scale: it provides services, including social security and family assistance payments, to millions of people in Australia and overseas, including to some of the most vulnerable members of our community. Efficiency initiatives, such as the diversion of resources to online rather than person-to-person channels and the phasing out of payments by cheque, can save money. But, as complaints to this office show, these benefits need to be carefully balanced against the potential for increased disadvantage to Centrelink's clients, some of whom have no access to the internet or mobile phones.

Significant issues

Service delivery

The office continues to work with DHS, highlighting areas of concern and making recommendations both formally and informally in relation to individual cases and more strategic issues.

This year the office published a follow-up report on recommendations the office had made in 2014 about Centrelink's service delivery. The office found that phone and online services, complaint and review process and records management continue to be key points of frustration.

The report detailed problems with access to phone services and the challenge of contacting Centrelink to have actions explained or decisions reviewed. These have remained recurrent themes in 2015–16. The inability to access Centrelink in order to fix problems with online services or generally to make a complaint resulted in added frustration.

In its response to the updated report, DHS advised that its facility allowing customers to request a call back, 'Place In Queue' (PIQ) would receive additional capacity. However, the office then learned that the PIQ facility was deactivated in July 2015 and that DHS is considering whether it will be reinstated pending the rollout of its managed telecommunications service.

Debts

In 2015–16 the office continued to liaise with and make suggestions to DHS about improving customers' experience of Centrelink debts. Based on complaints the office has found that customers often:

- are unaware of a debt until contacted by a debt recovery agency

- are unable to talk to DHS by phone to find out why they have a debt, to make payment arrangements or to request a review of a debt decision

- face difficulties gathering evidence to verify or challenge decisions when very old debts are raised

- have been pursued for debts despite DHS agreeing there was a factual or system error affecting the debt and/or its calculation.

Encouragingly, in the last of these, DHS has advised that it will change its guidance to staff on their capacity to temporarily write-off debts in those situations.

Customers' experience of debt will continue to be a focus of our engagement with DHS.

DHS—Child Support

DHS's Child Support program has a variety of functions in relation to the transfer of payments between separated parents or other carers of eligible children.

The Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about DHS's administration of child support cases.

The number of complaints received about Child Support has remained fairly stable (see Figure 2). Collection activities remain the main source of complaint.

The Ombudsman made an extensive submission to, and appeared before the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs' Inquiry into the Child Support Program. The Committee published its report From Conflict to Co-operation in July 2015. One area highlighted in that submission—and also in our Annual Report 2014–15 and in our discussions with DHS, the DSS and the Australian Taxation Office (ATO)—has been the impact of corrected tax assessments on child support liability. Complainants have found that, while the ATO can quickly correct a wrongly inflated assessment of taxable income, DHS cannot. As a result, people have been pursued for child support 'arrears' based on incomes which were incorrectly reported due to errors (sometimes beyond their control) which have since been corrected. This situation can also affect recipients of Child Support: their rates of Family Tax Benefit are affected by Child Support received, or deemed to have been received. It appears that a legislative solution is required to address this anomaly. The office notes that the Standing Committee has recommended changes to the legislation, but that the Government is yet to respond to the Committee's report.

Most child support-related complaints arise from collection activities, with payers who experience financial difficulties complaining that the agency has not or cannot take their changed capacity into account. Payees complain that the agency does not actively collect their ongoing child support payments, cannot tell them what collection action it has taken and cannot give them information about the payer's actual financial circumstances so that they can form a view about what is reasonable.

Department of Employment

During 2015–16 complaints about the Department of Employment increased by 45.1 per cent from 344 complaints in 2014–15 to 499 complaints in 2015–16. This followed a 53.1 per cent increase in 2014–15 from 224 complaints in 2013–14.

Significant issues

Complaints about the department are overwhelmingly about job services providers. Common complaints include the standard of services, complaint-handling outcomes and dissatisfaction with expected job search and training activities.

Jobactive rollout

Since July 2015 job services providers have been able to recommend that DHS reduce an income support payment as a form of penalty where the jobseeker has failed to attend an appointment.

The office received many complaints from people who had their payment suspended for failing to attend an interview, who have been referred to Centrelink or, not knowing the reason for their reduced pay and how to resolve it, have been unable to call Centrelink for an explanation. Coupled with the difficulty of accessing Centrelink phone lines, some have experienced significant delays in having their payments restored.

Referrals under the Jobactive Deed

A long-standing and frequent source of complaint is that employment providers do not send jobseekers to activities or Work for the Dole placements relevant to their previous experience or skills, but focus on low skill positions and entry level activities (for example cleaning jobs and resume-writing courses).

The Jobactive Deed, which sets out the arrangements between the department and the provider, provides no effective way for the department to direct that efforts be more targeted and focused on the participants' prior experience. The Deed simply requires that the provider must use its 'best endeavours' to place a jobseeker in a 'suitable' activity, job or placement. The Jobactive Deed is in place until 2020.

The office continues to see and investigate complaints where it appears that there are manifestly unreasonable referrals, for example where a person with an established physical injury is referred to a labouring position.

Department of Social Services

In March 2016 the Ombudsman published a report on Income Maintenance Periods (IMPs) and Special Benefit. These are administered by DHS according to instructions provided by DSS.

When someone receives an employment termination payment (for example, redundancy pay) he or she may have to serve an IMP during which time he or she cannot receive certain Centrelink payments for the period that the termination payment represents.

In 2014–15, 54 160 IMPs were applied. Complaints showed that it was not unusual for people to become aware of these non-payment periods only after they had spent their termination payment and were in financial difficulty.

DHS has discretion under social security law to reduce the length of IMPs in certain circumstances. It can also pay 'Special Benefit', a payment designed for people who are in financial hardship and who, for reasons beyond their control, are unable to earn a sufficient livelihood for themselves and their dependants.

The office found that DSS's instructions, which detail the rules under which Special Benefit may be paid to people serving an IMP, were too narrow to allow DHS to exercise fully its discretion under the legislation.

DSS's and DHS's responses to the Ombudsman's recommendations were positive and encouraging. DSS agreed to amend its Guide to Social Security Law and DHS its Operational Blueprint, so staff would be aware that they could take the particular circumstances of an individual into account when considering their discretion to shorten the non-payment period and/or to pay Special Benefit. DSS also agreed to continue to review the Guide to Social Security Law to ensure clarity around the IMP rules and how they work. DHS agreed to tell people about Special Benefit and the circumstances in which they might be eligible to receive it.

National Disability Insurance Agency

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) is responsible for administering the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a government scheme that funds support for people with permanent and significant disability to help them take part in everyday activities.

The NDIS was established in a number of trial sites around Australia from July 2013. From 1 July 2016 the scheme will be fully rolled out in stages over three years. The arrangements for accessing the services of the NDIS vary depending on the state or territory in which participants live.

The Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate the administrative actions of the NDIA. During 2015–16 the office received 62 complaints about the agency. While this represents many more than the 25 complaints received during 2014–15, the increase is not unexpected given the increase in the number of people entering the scheme over the past year.

Common issues in complaints included:

- delays in scheduling a planning meeting

- dissatisfaction with an assigned planner

- confusion or unhappiness regarding the planning process

- conflicting or inadequate information about the scheme

- delays in paying for goods and services delivered

- confusion or dissatisfaction with the NDIA's internal review and complaint-handling arrangements.

During 2015–16 the office worked closely with the NDIA to provide feedback on issues arising from complaints, and will continue to do so as the national rollout of the scheme commences from 1 July 2016.

Major activities

Trial site consultations

Over the past year the office visited the Hunter (NSW), Barwon (Vic), South Australian and Tasmanian trial sites to meet with local NDIA staff, peak bodies, advocates and participants. These visits have the dual purpose of deepening our understanding of people's experience of the NDIS, and of building community awareness of our role in handling complaints. The office expects to visit the Perth Hills, Barkly (NT) and North Queensland regions during 2016–17 to conduct similar consultations.

The office has also given presentations at a number of public forums, in conjunction with state and territory disability organisations, about our respective roles in handling complaints about the NDIS.

Submissions

In 2015–16 the office made submissions to:

- the Department of Social Services' review of the National Disability Advocacy Framework (July 2015)

- the Senate Education and Employment Standing Committee's inquiry into 'current levels of access and attainment for students with disability in the school system, and the impact on students and families associated with inadequate levels of support' (August 2015)

- the Senate Community Affairs Reference Committee's inquiry into 'violence, abuse and neglect of people with disability in institutional and residential settings, including the gender and age related dimensions, and the particular situation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability, and culturally and linguistically diverse people with disability' (September 2015)

- the statutory review of the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (October 2015)

- the Department of Social Services' review of the National Disability Advocacy Program (June 2016).

These submissions are available online on the respective reviewing bodies' website.

Broader disability oversight

In addition to handling complaints about the NDIA, the Ombudsman also has a role in ensuring that Commonwealth government agencies deliver services, including complaint services, in ways that take account of the different needs of its users.

In 2015–16 the office held discussions with government agencies, oversight bodies and community organisations about providing services for people with disabilities.

Commonwealth Ombudsman's Disability Complaint-Handling Forum

In May 2016 the Ombudsman's office convened its first Disability Complaint-Handling Forum. This brought together representatives of Australian, state and territory government agencies, oversight agencies and peak disability bodies to discuss how best to encourage, receive and handle complaints from people with disability.

In 2016–17, the office will coordinate a number of working groups for government and non-government agencies to foster continued learning and collaboration in this area.

Indigenous

Major Activities

Community Development Program (CDP)

The CDP is an employment program which operates in 60 regions in remote Australia. More than 80 per cent of CDP participants are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

Since the CDP commenced in July 2015 our office has observed a significant increase in the number of compliance penalties being applied to Indigenous Australians in remote communities. The office will continue to monitor and investigate the program's administration through complaints and feedback received from our stakeholders and members of the public.

In December 2015 the government introduced the Social Security Legislation Amendment (Community Development Program) Bill 2015 (the CDP Bill) which included measures for job seekers to receive their payments directly from a CDP provider, rather than through Centrelink. Providers would also have the power to apply financial penalties if job seekers did not comply with their mutual obligations.

Our office made a submission in response to the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet's consultation paper outlining the proposed changes and the development of the legislative instruments supporting the Bill.

Our submission focused on the lessons learned from our oversight of the CDP and its predecessor programs and our concerns about the proposed compliance framework. The office was concerned about CDP providers being able to apply mandatory penalties based on hourly non-attendance; about providers having the power to determine reasonable excuses and exemptions and to undertake compliance reviews; and the creation of a new internal review framework separate to the DHS internal review framework.

The office suggested a number of measures to ensure that the proposed compliance framework contains adequate safeguards for job seekers.

Administration of Income Management for 'Vulnerable Youth'

In February 2016 the Ombudsman published a report on the Administration of Income Management for 'Vulnerable Youth'. DSS is the agency responsible for the Income Management (IM) legislation and associated policies, and DHS administers it through Centrelink.

IM is designed for people receiving income support payments who are considered to be at a higher risk of social isolation and disengagement, to have poor financial literacy and to be participating in risky behaviour. Under the current vulnerable youth measure, IM is automatically applied to people who live in an IM declared area and are classed as 'vulnerable youth' by virtue of their age and their qualification for a particular Centrelink payment. This can include children aged under 16 years who receive Special Benefit; people aged 16 years and over who have been granted the Unreasonable to Live at Home (UTLAH) payment; and people under the age of 25 who receive a Crisis Payment due to prison release.

In the report, areas of concern included:

- failures of the automated decision-making process

- failures by Authorised Review Officers to consider all the mandatory legislative criteria

- the lack of any process to allow DHS to give effect to the legislative power to revoke a determination and exit a person from IM when that person was otherwise eligible

- decision letters that did not provide adequate reasons for decisions and a failure to inform people of their rights.

The Ombudsman made ten recommendations to DSS and DHS. The departments responded positively to around half of those recommendations and have taken steps towards improving some processes and policies. The office will continue to work closely with them to monitor the implementation of the recommendations.

Engagement

This year, the office continued to engage with community and government stakeholders.

A number of Indigenous roundtable discussions were held in Adelaide, Canberra, Melbourne and Perth. These offered community stakeholders an opportunity to identify key issues and problems affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

During the year the office also travelled to Alice Springs, Katherine, Darwin, Shepparton, Murray Bridge, Tamworth, Armidale and the Sunshine Coast to meet with government and community stakeholders.

In June 2016 the office hosted an Indigenous Interpreter Service Forum, in partnership with the Northern Territory (NT) Ombudsman. This was an opportunity for people to share their views on the accessibility and use of Indigenous language interpreters by Government agencies. These views will inform the own motion investigations being conducted by the NT Ombudsman and this office into the use and accessibility of Indigenous language interpreters.

Improving Indigenous complaint-handling

Creative approaches can be useful in making government complaint systems more accessible and meaningful for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The office wants to resolve individual issues and to ensure that complaints and feedback lead to systemic improvements.

Indigenous complaint-handling forums were conducted in Canberra and Darwin. Indigenous leaders, community organisations, government agencies and oversight bodies discussed accessibility issues. As a result of these forums, the office has started four key projects.

Commonwealth Government Community of Practice — Indigenous complaint-handling

The Community of Practice is a forum for Commonwealth Government agency representatives to share contacts, information, ideas and resources with a view to improving Indigenous complaint-handling within and across government. Eventually, the office hopes to use this forum to develop and implement some agreed best practice Indigenous complaint and feedback principles.

Right to Complain Strategy

The office has established a working group made up of government and non-government stakeholders focused on improving the uptake rate and use of government complaint and feedback mechanisms by Indigenous people and communities.

The group aims to develop a communication strategy promoting people's right to complain and/or raise issues or concerns, targeting Indigenous people and communities and encouraging the view that complaints and feedback are important and can make a difference to the individual and more broadly.

Australian and New Zealand Ombudsman Association (ANZOA) Interest Group

The office is leading an ANZOA interest group made up of participants from Australian and New Zealand government and industry ombudsmen.

Meeting regularly, the group will focus on sharing information, contacts and resources, as well as supporting a more coordinated approach to Indigenous outreach and engagement between member organisations. It aims to establish a coordinated approach to encourage the agencies and organisations the office oversees to make their complaint processes more accessible and effective for Indigenous people.

Information Sharing Portal

The office developed an online platform using Govdex to facilitate the sharing of ideas, contacts, tools, strategies, resources and information to support and improve Indigenous complaint-handling.

The portal is available for use by community groups, government agencies oversight bodies and other interested parties, and will support the work of the various working groups, interest groups and communities of practice focused on improving Indigenous complaint-handling.

POSTAL INDUSTRY OMBUDSMAN

Case Study

Sam has a Post Office (PO) Box at his local post office. After receiving no mail for over a month, he received a few letters and a collection card. When he took the card into the Post Office, he received a bundle of undelivered mail. Post Office staff said that the mail had been bundled as it had not been collected and because the PO Box was too full.

Sam asked Australia Post for an explanation. He was not satisfied with the response, so he complained to the office.

As a result of the office's investigation, Australia Post agreed to consider the actions taken by the Post Office staff and review its procedures for dealing with uncollected mail. Australia Post also provided a written explanation and apology and refunded the service fee as a gesture of goodwill.

Overview

The Ombudsman is also the Postal Industry Ombudsman (PIO). The PIO role was established in 2006 to provide an industry Ombudsman service for postal operators and their customers.

Australia Post is a mandatory member of the scheme, while Private Postal Operations (PPOs) can register voluntarily. As at 30 June 2016, there were six PPOs on the register.

The PIO can investigate complaints about postal or similar services provided by Australia Post and PPOs. The Ombudsman can also investigate complaints about administrative actions and decisions taken by Australia Post. Most commonly, people complain to the PIO about lost letters or parcels, delivery issues (including the failure to attempt delivery of parcels and incorrect safe drop procedures), and delay in the arrival of postal items.

Statistics

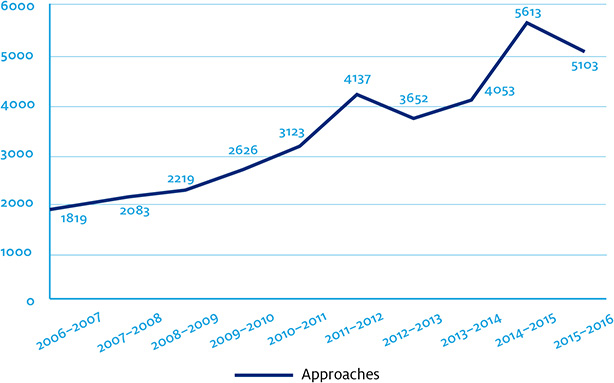

In 2015–16, the office received 5113 in-jurisdiction complaints, a nine per cent decrease on the previous financial year. In general, the number of complaints has grown steadily since the PIO was established.

Figure 3: All approaches for Australia Post (Commonwealth and Postal Industry Ombudsman)

Most complaints were about Australia Post (5103). Only ten complaints concerned Private Postal Operators.

The office did not investigate all complaints received. The main reasons for declining were that:

- the complaint was outside the office's jurisdiction (for example, it was about employment or not concerning a postal or similar service matter)

- the complainant could not show that he or she had made a reasonable attempt to resolve the issue with Australia Post or the PPO, or

- it was assessed that no better practical outcome was likely.

In 2015–16 the office finalised 168 investigations, 141 of them were under the PIO jurisdiction and 27 under the Commonwealth Ombudsman jurisdiction.

Second-chance transfers—Australia Post

The office has an arrangement with Australia Post where complaints can be referred to them. These are usually uncomplicated matters or those the office thinks Australia Post should be able to offer a satisfactory outcome.

Most transferred complaints were successfully resolved by Australia Post. However, complainants can return to our office if they are dissatisfied with Australia Post's response.

In 2015–16 the office transferred 1221 complaints to Australia Post for reconsideration. Around 12 per cent (152) of these complainants returned to our office. The office investigated a small proportion of these, but were generally satisfied with Australia Post's response and no investigation was warranted.

Fees

The PIO seeks to recover its costs from the industry by charging investigation fees. Fees are calculated and applied after each financial year and returned to Consolidated Revenue. Figures for 2015-16 will be available in next year's annual report.

The fees received for 2014–15 were $551 690 for Australia Post and $2933 for FedEx, totalling $554 623.

The cost recovery arrangements in place for the PIO function do not adequately reflect the true cost to the office of providing the service. The office will work with government and industry stakeholders in 2016–17 to review its cost recovery payment structure.

Significant issues in the reporting period

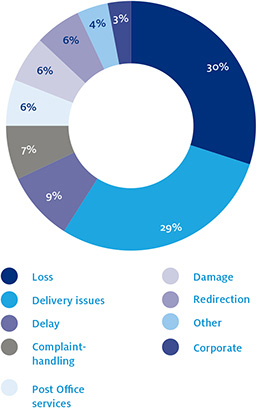

Complaints about loss, delivery, and delay are the three most common issues concerning Australia Post.

Figure 4: Complaint Issues received by Postal Industry Ombudsman in 2015–16

- Loss

The most common complaints received by the PIO relate to lost letters or parcels. In these cases, the dispute typically arises because Australia Post believes it has correctly delivered an article, but the addressee claims it has not been received.

- Delivery

Delivery issues are mainly about failure to attempt delivery of parcels, incorrect safe drop procedures and failure to obtain a signature on delivery when required to do so.

- Delay

Complainants often complain to the PIO about delayed delivery of a letter or a parcel. Post items may be delayed due to routing errors or incorrectly addressed envelopes.

Issues from 2014–15

In our last annual report the office identified some issues relating to newly-introduced services and the Government's reform agenda:

- Australia Post—MyCustomer

Australia Post introduced its new enquiries management system, 'MyCustomer', in late 2014. It experienced some early technical problems, which resulted in a backlog of complaints and some delays. This in turn led to a rise in complaints to the PIO. Australia Post resolved the technical issues and the office considered this to be finalised.

- Australia Post—ShopMate

In October 2014, Australia Post launched its ShopMate service for customers who want to purchase goods from sellers in the US who do not offer shipping to Australia. PIO received a significant number of complaints relating to the dimensions of articles and whether they exceeded ShopMate's size limits. Other complaints related to a lack of clarity regarding pricing calculations, and delivery problems that occurred before arrival at Australia Post's warehouse.

In response to PIO recommendations, Australia Post has improved the information available to consumers concerning packaging dimensions, size limits and costings. While the office continues to receive ShopMate complaints, these are mostly about delay, loss or delivery, rather than the more systemic issues of the previous financial year.

Of the 80 complaints received in 2015–16, around eight per cent required further investigation, with an appropriate remedy provided in each case.

- Reform of Australia Post

In March 2015, the Federal Government approved Australia Post's request for regulatory reform of its letters service including an increase in the basic postal rate and the introduction of a regular and priority letter delivery service. The introduction of a Regular and Priority letter delivery service for consumers and an increase in the Basic Postage Rate from 70 cents to $1 came into effect on 4 January 2016.

The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has responsibility under the Competition and Consumer Act 2010 to oversee the prices of Australia Post's notified letter services. On 9 December 2015, ACCC released its decision to not object to Australia Post's price notification.

The office received a small number of complaints concerning the increase in the cost of the basic postal rate and the introduction of the two-speed mail service. However as the pricing decision had been reviewed by the ACCC and the two-speed mail service was supported by Government, the office did not investigate these complaints.

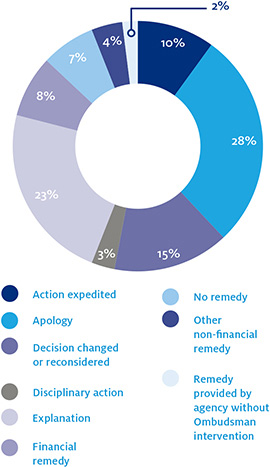

Major outcomes—remedies

The PIO carries out its functions by investigating individual complaints, identifying and pursuing systemic problems, and acting on emerging issues.

Figure 5: Remedies to complaints received by Postal Industry Ombudsman

As outlined in Figure 5, a number of the office's investigations have resulted in better outcomes for complainants. These include expedited action, comprehensive searches for lost items, apologies, compensation payments, postage refunds, staff being counselled or disciplined, and the provision of better explanations by the PPO or the office.

Additional reporting on the PIO function as required under s 19X of the Ombudsman Act

- Details of the circumstances and number of occasions where the Postal Industry Ombudsman has made a requirement of a person under s 9

The Postal Industry Ombudsman made no requirements under section 9 during 2014–15.

- Details of the circumstances and number of occasions where the holder of the office of the Postal Industry Ombudsman has decided under subsection 19N (3) to deal with, or to continue to deal with, a complaint or part of a complaint in his or her capacity as the holder of the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman:

There were no occasions where a complaint —or part of a complaint—was transferred from the Postal Industry Ombudsman to the Commonwealth Ombudsman under subsection 19N (3).

- Details of recommendations made in reports during the year under section 19V; and statistical information about actions taking during that year as a result of such information:

The Postal Industry Ombudsman made no reports during the year under section 19V.

IMMIGRATION OMBUDSMAN

Overview

The Immigration Ombudsman investigates complaints about immigration detention and general immigration matters, including Customs, and also monitors the department's compliance activities. The office's statutory reporting function, for people who have been detained for more than two years, is a major part of this oversight function, as is the office's program of regular inspections of immigration detention facilities.

Complaints

In 2015–16 the office received 2341 complaints about the department, compared with 1913 in 2014–15, an increase of 22 per cent. Of these, the office investigated 496 (21 per cent).

The reasons the office declined to investigate included:

- the matter was out of jurisdiction (for instance it might relate to the actions of a minister)

- the complainant had not approached the agency first (the office gives the agency the opportunity to rectify the matter first)

- matter complained of was more than 12 months old

- there was no prospect of getting a remedy for the complainant.

Common themes for detention complaints are similar to those in previous years: loss or damage to detainees' property, placement within the detention network and medical issues such as access to specialist care, appropriate treatment for injuries and illness, and delays in the processing of claims for asylum.

General immigration complaints showed a large increase regarding delays in granting citizenship. The office sought a briefing on this issue and was advised that the department is taking actions to minimise the delay for people applying for citizenship, taking into account the need to ensure that appropriate attention is given to identity and security matters. The office is maintaining a watching brief on these delays.

Delays in processing visa applications, as well as dissatisfaction with visa decisions, remain a common cause for complaints.

Investigations

In 2015–16 the office finalised an own motion investigation into the operation of the Tourist Refund Scheme (TRS).

The office investigated a number of complaints about the operation of the TRS, in particular the '30 minute rule'. This rule, imposed by the department, requires departing passengers who wish to claim a refund of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) on goods purchased before departing Australia, to present themselves at the airport's TRS counter at least 30 minutes prior to their flight's scheduled departure time.

The stated purpose of the rule is to ensure people claiming a refund allow sufficient time to do so, so that flight departures are not delayed.

The department has acknowledged that the 30 minute rule is not supported by legislation and says it is considering how changes to the processes at the TRS facilities can be implemented.

The Ombudsman made two recommendations:

- that, as an interim measure, the department should take all reasonable steps to ensure that travellers who wish to claim a TRS refund are able to do so in a way that is consistent with the law.

- that the department considers the permanent use of the drop box facility at TRS facilities at all international points of departure, and takes all necessary steps to ensure the appropriate regulations are in place to give effect to this arrangement.

The department accepted the recommendations and the office will monitor the implementation of these changes in 2016–17.

Liaison and stakeholder engagement

The office continues to meet regularly with the department to discuss systemic issues and matters of interest to both agencies. The office also received briefings from the department where detailed information was requested on a specific issue.

The office continued a program of community roundtable meetings as well as liaison with advocacy groups such as the Refugee Council of Australia.

The office also hosts quarterly meetings with the heads of the Australian Human Rights Commission, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Australian Red Cross and Foundation House.

Compliance monitoring

In 2015–16 the office continued its ongoing own motion investigation into the department's (now the Australian Border Force—ABF) compliance activities involving locating, detaining and removing unlawful non-citizens. The investigation provides the government and the public with assurance that the ABF's processes are lawful and in accordance with good practice.

This is important as a departmental delegate may approve warrants allowing immigration officers to enter and search premises under s 251 of the Migration Act 1958. The office presented sessions to compliance staff on the functions of the Ombudsman's office and observed field compliance operations in the following locations:

- Griffith—August 2015

- Melbourne—November 2015

- Adelaide—June 2015

- Perth—June 2015.

The office observed that the ABF officers in the field act in a professional manner, and the office did not identify any areas of significant or systemic concern. However, some areas for improvement were identified. The office recommended that the ABF:

- ensures that when detaining a person, departmental officers secure and tag the detainee's valuables in bags and provide a receipt to the detainee

- affords detainees a reasonable opportunity to secure and dispose of their assets before their removal, where practical

- examines options to allow the ABF to seize identity documents not belonging to household members

- adopts guidelines for the amount of time a person may be questioned without breaks

- facilitates the claiming of superannuation by persons being removed, by providing the appropriate form as a standard part of the removal process

In December 2015 the department advised that a number of reviews were underway that covered most of these recommendations.

People detained and later released as 'not-unlawful'

The department provides the office with six-monthly reports on people who were detained but later released with the system descriptor 'not-unlawful'. This descriptor is used when a detained person is found to be holding a valid visa, usually because of case law affecting his or her particular circumstance or because of notification issues surrounding visa cancellation decisions.

For the calendar year 2015, the department reported that out of a total of 7563 people detained, 22 (0.29 per cent) were later released as not-unlawful, compared to 29 (0.83 per cent) out of 3486 persons detained during 2014. The office is satisfied that detention in these cases was not the result of systemic issues or maladministration.

However, the average time people have spent in detention prior to errors being identified, and their subsequent release as 'not-unlawful', has increased from an average of five to six days in 2014 to an average of 12 days during the first half of 2015. For the latter half of 2015, this average increased to 65 days. It is understood that this increase is the result of significant delays in identifying lawfulness in five individual cases.

Immigration detention reviews

Statutory reporting (two-year review reports)

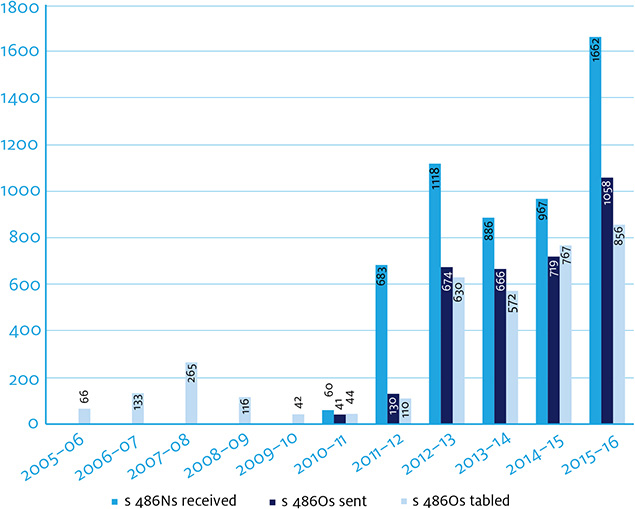

When a person has been in immigration detention for two years, and then after every six months, the Secretary of the department must give the Ombudsman a review, under s 486N of the Migration Act 1958, relating to the circumstances of the person's detention.

Section 486O of the Migration Act requires the Ombudsman to give the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection a report on the appropriateness of the arrangements for that person's detention. The Ombudsman also provides a de-identified version of the report to the Minister, which is tabled in the Parliament.

In 2015–16 the number of people subject to reporting under s 486O was at its highest point since the oversight function commenced in 2005. Although there was an increase in the number of people released from detention, the number of cases no longer subject to reporting was matched by new cases, including people detained after their visas had expired or were cancelled due to character concerns. The number of reportable cases therefore remained steady, although it is expected to decline in the next financial year.

The office conducts interviews, primarily by telephone, with people in long-term detention. This highlights individual and emerging systemic issues experienced by people in community detention and in detention facilities.

Figure 6: Number of reports received and tabled by Immigration Ombudsman

In 2015–16 the Ombudsman made a total of 490 recommendations, compared with 172 the previous year. Of these recommendations, 154 remained open at the time of tabling.

Issues raised in the two-year reports include:

- the continued detention (in some cases over six years) of people who have been found to be owed protection, but have received an adverse security assessment

- people who have been found not to be owed protection, but who are unwilling to return to their home country voluntarily and cannot be returned involuntarily

- placement considerations for individuals to be closer to family support

- incomplete or inaccurate health records which may have adversely affected treatment of detainees

- concerns arising from the mix of the detainee population at certain centres

- delay in status resolution for certain groups of transitory persons who were returned to Australia from a regional processing centre

- continued detention of individuals with vulnerabilities and/or significant mental health concerns.

Detention Inspections

The Ombudsman oversights immigration detention and has done so since 2005.

During 2015–16 our detention inspections team visited the immigration detention facilities listed in Table 3 below.

| Immigration Detention Facility | Location | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation | Brisbane QLD | Aug–Sep 2015 Feb 2016 |

| Manus Island Regional Processing Centre | Papua New Guinea | Oct 2015 May 2016 |

| Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre | Melbourne VIC | Nov 2015 Jun 2016 |

| Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation | Melbourne VIC | Nov 2015 Jun 2016 |

| Nauru Regional Processing Centre | Nauru | Sep 2015 Feb 2016 |

| North West Point Immigration Detention Centre | Christmas Island WA | Nov 2015 Jan 2016 |

| Perth Immigration Detention Centre | Perth WA | Jan 2016 |

| Perth Immigration Residential Housing | Perth WA | Jan 2016 |

| Sydney Immigration Residential Housing | Sydney NSW | Dec 2015 Jun 2016 |

| Villawood Immigration Detention Centre | Sydney NSW | Dec 2015 Jun 2016 |

| Wickham Point Immigration Detention Facility | Darwin NT | Aug 2015 May 2016 |

| Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre | Northam WA | Aug 2015 Apr 2016 |

The inspection function is undertaken under the Ombudsman's own motion powers1, and in accordance with our jurisdiction to consider the actions of agencies and their subcontractors. Each visit generates a report recording the observations made and makes suggestions. As at 30 June 2016 the office submitted 15 reports to the department. The office is awaiting the department's response to eight of them. Despite the delay in responding to the reports, the level of cooperation experienced within the Australian immigration detention facilities is generally high. This is because Detention Service Providers2 and on-site departmental officers are aware of the office's role and the legislative framework it works within.

Information sharing

Limitations on information sharing between relevant stakeholders continued to be a substantive issue for the management of the Regional Processing Centres.

The office was advised in November 2015 by senior ABF officers that this had been rectified, but the office's observations and discussions in February 2016 indicated otherwise. The office's subsequent visit to a Regional Processing Centre in May 2016 indicated that steps to address this shortfall had now been implemented, albeit with some residual issues.

Placement of detainees within the network

The Commonwealth, through the ABF and its respective facility Superintendents, is required to exercise a duty of care to all detainees3. This means that decisions regarding detainee placements within the facility and the broader network cannot be made in isolation.

The office acknowledges that the ABF is required to manage the operational and logistical pressures on the network and that this means that some detainees will be placed in more remote and isolated locations such as Christmas Island.

The office is concerned that most operational decisions do not take account of key supporting information from status resolution or service provider staff, and are made based upon generic risk profiling. It appears that when a person is placed in a particular facility, little consideration is given to family connections, legal cases and medical treatment.

During this period, the office has noted an increase in the level of non-compliant behaviour by detainees. This may in part be attributed to the increasing pressure on them because their families are prevented from visiting due to distance or cost.

The office considers that where the department restricts a detainee to a facility or transfers detainees between facilities, this should be done with consideration to individual circumstances and not be based solely on the detainee's ethnicity, criminal history, age or other generic factors. The office notes the introduction of the National Detention Placement Model in the later part of this reporting period and acknowledge that this has the potential to address our key concerns. The office will continue to monitor the effectiveness of this placement model.

Risk assessments and use of mechanical restraints

In May 2015, before the establishment of the ABF, a directive was issued concerning the manner in which detainees are transferred. In summary, this removed individual assessments of risk and substituted a generic risk profile based on cohort and immigration status. Although this directive has been recently rescinded, it is the case that for a significant part of this reporting period, the decision to transport detainees while using mechanical restraints was based solely on generic risk profiling.

Where the department decides to restrain a detainee for transportation or other reasons, this must be exercised with consideration to individual circumstances and not be solely based on the detainee's ethnicity, criminal history, age or other generic influence. Service providers have revised the security risk assessment tool so that in future, decisions to restrain an individual will be based on individual circumstances.

It remains that ABF must ensure that force is not applied in a punitive manner and can be fully supported by the individual's circumstances rather than a generic group profiling.

Continuum of Force

The use of restraints and force when dealing with detainees has increased. Under some circumstances the use of force is both necessary and appropriate to protect the individual or others. However when the office has examined the incident reports involving unplanned use of force, there has been little or no evidence of de-escalation techniques having been applied. The Continuum of Force commences with verbal de-escalation and escalates through a number of phases to the ultimate use of deadly force. It is apparent that service provider staff members, in particular, consider the application of physical force to address non-compliant behaviour as the start-point rather than the mid-point of the continuum.

Internal complaint-handling

One of the primary focuses for this inspection cycle was the management of internal complaints by both the ABF and its service providers. Good complaint management4 requires a systemic approach that is timely, appropriate and responsive.

Overall the standard of complaint management was reasonable, although there was considerable variation between the various facilities.

The office is concerned that complaint resolution and recording practices are inconsistently applied by the ABF and their service providers for all complaints that are resolved locally. Furthermore it would appear that there is considerable variation in the management of complaints from individual officers within the various facilities.

While the office understands that there is an overarching complaint policy, it would appear that it is not well understood or applied across the detention network. An alignment of the processes and procedures across the network to reflect good complaint-handling practices and in particular the provision of detailed responses to complaints that address the issues, would lead to consistent and effective administrative practices.

Access to mobile telephones

Since 2010 the office has raised the issue of the inequity within the department's policy relating to the possession of mobile telephones by detainees. Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs) are the only detainee category not permitted to have mobile telephones in their possession. While the office has been repeatedly assured that this inequity is being addressed, the office is yet to see any substantive evidence to support this.

Impact of duration of detention/processing on mental health and welfare

Management of the welfare and engagement function has been applied with varying degrees of success across the network and regional processing centres. Welfare and engagement is pivotal to the good order, security and wellbeing of detainees within the network and those held in the Regional Processing Centres. As the office has previously stated, the positive engagement of detainees in an enclosed and restrictive environment is directly related to the management of their ongoing physical and mental health5.

It appears from our engagement with the mental health teams, welfare teams and the detainee/asylum seeker/refugee population that the mental health of people who have been detained for extended periods has deteriorated further. This is particularly notable among refugees and asylum seekers and those detainees who have had their visas cancelled on character grounds.

OVERSEAS STUDENTS OMBUDSMAN

The Overseas Students Ombudsman (OSO) investigates complaints and appeals from intending, current and former international students about private colleges, universities and schools.

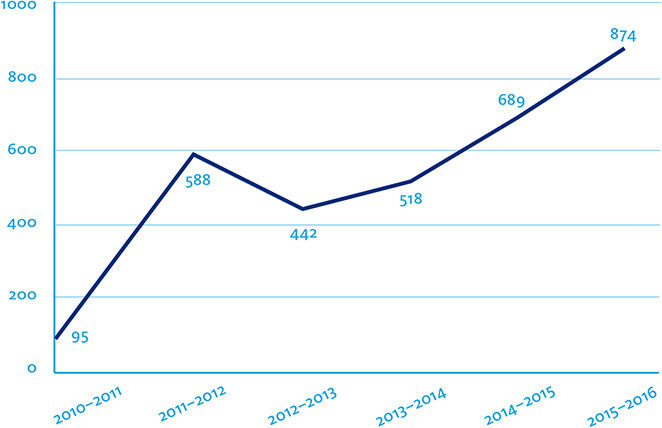

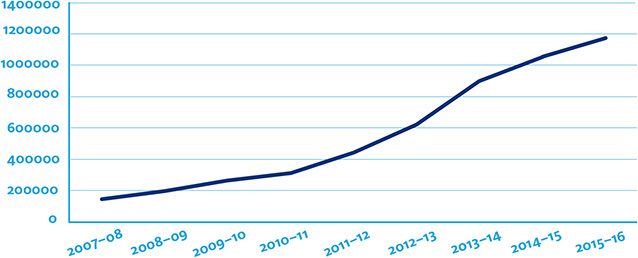

In 2015–16, the OSO received 874 complaints and appeals, 27 per cent more than in 2014–15 and 69 per cent more than in 2013–14. This represents a correlation between the considerable and sustained growth in the international student sector and the number of complaints received.

Figure 7: Overseas Students Ombudsman complaints received by year

In 2015–16 the office started 315 complaint investigations and completed 291, compared to 238 investigations started and 239 completed last year.

Of the completed investigations, 56.7 per cent were resolved in favour of the provider; and 25.7 per cent in favour of the complaining student. In 17.6 per cent of cases the office's investigation outcome favoured neither party because the case was otherwise finalised. For example, the provider fixed the problem quickly before the office needed to fully investigate or the office decided after starting its investigation that the issue would be better dealt with by another complaint-handling body.

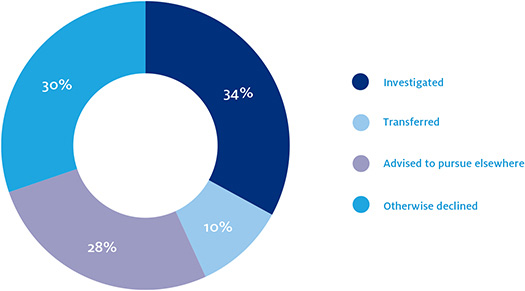

The office finalised 575 complaints without investigating (compared to 441 last year) because the office:

- formed a view on the documents provided by the student

- referred the student back to his or her education provider's internal complaints and appeals process, or

- transferred the complaint to another complaint-handling body as provided by s 19ZK of the Act.

Figure 8: How complaints were finalised by Overseas Students Ombudsman

Table 4: Complaints transferred to other complaint bodies Complaint body Number of complaints transferred in 2015–16 Number of complaints transferred in 2014–15 Australian Human Rights Commission 1 0 Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) 21 19 Fair Work Ombudsman 1 0 Office of the Training Advocate, SA 12 10 Tuition Protection Service (TPS) 55 33 Total 90 62

Helping students through impartial complaint-handling

Complaint issues

The two main complaint types continued to be provider refunds and fees disputes (325 complaints) and providers' decisions to refuse a student transfer to another provider under Standard 7 of the National Code (174 complaints/external appeals).

Providers' decisions to report students to the Department of Immigration and Border Protection for failing to meet attendance requirements under Standard 11 (115 complaints/external appeals) moved from the fourth to the third most common issue.

The fourth main complaint issue was providers' decisions to cancel, suspend or defer a student's enrolment under Standard 13 (104 complaints/external appeals).

Student Feedback

"Hi, Thank you very much for your reply. I am really glad to see that you have taken action against my complain. This would have never happened in my country. I am proud to be living in Australia, where even complaints from foreigners are listen without any discrimination. [My education provider] was not even listening to me before but after lodging this complain and action taken by OSO, he has now been really respectful to me. Once again thank you OSO" (sic)

Reports to the regulators

The OSO has the power under s 35A of the Act to disclose information about providers of concern to the relevant regulator. In 2015–16 the office made six s 35A reports to the Australian Skills Quality Authority, compared to three last year.

Reports on trends and systemic issues

Our publications this year were:

- a report on the OSO's first four years of operations, including key outcomes and activities

- a Written Agreement (Fees and Refunds) student fact sheet to help students avoid the problems that commonly lead to complaints

- an updated version of our Written Agreements Issues Paper and Provider Checklist to reflect the December 2015 Education Service for Overseas Students 2000 changes

- Four quarterly statistical reports highlighting key issues, trends and outcomes

- two e-newsletters for private education providers

- an e-newsletter for international students.

The office participated in interagency meetings about the Department of Health's review of the Overseas Student Health Cover Deed of Agreement, providing observations based on issues identified in our complaint investigations. The office also collaborated with the publication Insider Guides that published an online article on the role of the OSO, which was promoted to students through social media.

Stakeholder engagement and promoting best practice complaint-handling

In 2015–16, the Ombudsman met with the embassies of Brazil, China and Indonesia to raise awareness of our role in helping students from these countries with complaints.

The office convened a complaint-handling panel at the Council for International Students Australia (CISA) national conference to highlight to the attendees their right to complain and who to contact for different issues. The office provided training to the new CISA Executive to advise where to direct students experiencing problems. The office also presented at the IDP Education Brisbane International Students Expo and the Australian Federation of International Students/Study Melbourne international student information day.

The office:

- collaborated with English Australia (EA) and the Australian Council of Private Education and Training (ACPET) to deliver three provider training webinars on course progress, attendance and best practice complaint-handling

- provided training through the International Student Advisors Network Australia (ISANA) and participated in an ISANA symposium on international student accommodation issues

- spoke at the EA, ACPET and ISANA national conferences as well as presenting at the Australian International Education Conference (AIEC) for the first time, and

- attended the NSW Ombudsman's University Complaint Handlers forum, which includes two private universities in the OSO's jurisdiction.

The office held regular liaison meetings with regulators, the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) and the Tertiary Education Quality Standards Agency (TEQSA), to discuss common issues as well as the Tuition Protection Service (TPS), the Department of Education and Training and the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) to discuss issues relating to international education and overseas student complaints.

Looking forward

In April 2016, the government released Australia's first National Strategy for International Education 2025 and the AIE2025 Roadmap, which envisages Australia's welcoming 720 000 international students each year by 2025. The strategy notes the OSO's role in supporting this growth by ensuring strong student protections.

As the international education sector continues to grow, the office expects to see a continued increase in complaints. The office wants to find out whether the current complaint arrangements meet students' needs and whether any changes could be made to strengthen or simplify student protections.

The office will have commenced that process before publication of this report by releasing a consultation paper on the external complaints avenues for international students.

Case study

A student complained to the OSO that her private education provider had cancelled her enrolment while she was overseas on holiday during the mid-year break. She was informed at the airport when she attempted to re-enter Australia that her visa had been cancelled. It seemed that her private education provider had informed DIBP that she had not paid her tuition fees and had therefore cancelled her enrolment. The student contended that she had paid her fees and should be allowed to continue studying.

The office found that the student had in fact paid her fees but had not labelled her bank transfer with sufficient identifying details. This meant that the provider was unable to establish that the bank transfer was hers. Some instalments were also paid several weeks late, but the provider had not followed this up with the student.

In addition, the office found that the provider had not notified the student in writing of its intention to cancel her enrolment for non-payment of fees, nor had it offered her an opportunity to lodge an internal appeal against its decision. This is a breach of Standard 13 of the National Code of Practice for Registration Authorities and Providers of Education and Training to Overseas Students 2007 (the National Code).

The office recommended that the provider update its cancellation policy to ensure that in such cases in future a letter is sent to the student, inviting him or her to appeal. The office also recommended that the provider follow up on all outstanding fees in a timely manner and revise its fee policy to document this process.

Finally, the office recommended that the provider reinstate the student's enrolment while it conducted an internal appeal, and to inform DIBP that the student's enrolment had been cancelled in error.

PRIVATE HEALTH INSURANCE OMBUDSMAN

Readers of previous PHIO annual reports: please refer to www.ombudsman.gov.au/about/private-health-insurance for more detailed complaint statistics on the private health insurance industry. From 2016–17, PHIO will be providing additional quarterly updates of complaint statistics online.

Context

The role of the Private Health Insurance Ombudsman (PHIO) is to protect the interests of consumers in relation to private health insurance. The Ombudsman is an independent body that resolves complaints about private health insurance and acts as the umpire in dispute resolution at all levels within the private health industry. The Ombudsman also reports and provides advice to industry and government about these issues. The office has a significant consumer information and advice role including managing the consumer website PrivateHealth.gov.au

Overview of 2015–16

The office of PHIO merged successfully with the Commonwealth Ombudsman on 1 July 2015. It is pleasing that the standard of service provided to complainants was maintained, and in some areas improved, as measured by audit and survey data. The level of overall satisfaction as reported by complainants to PHIO increased from 84 per cent in 2014–15 to 85 per cent in 2015–16.

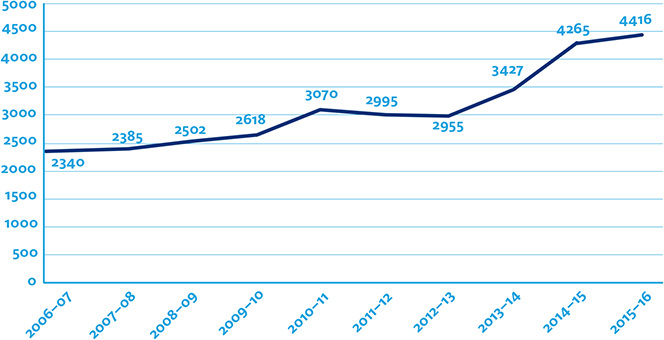

After several years where PHIO complaint levels remained steady, the past two years have seen an increase. In 2015–16, PHIO received 4416 complaints, compared with 4265, in 2014–15 and 3427 in 2013–14.

In our consumer information and advice role, the office received 3999 consumer information enquiries in 2015–16, of which 59 per cent were received through consumer website PrivateHealth.gov.au

Figure 9: Total complaints by year received by Private Health Insurance Ombudsman

Complaints about Private Health Insurers

Table 5 shows the number of complaints and disputes6 received about registered private health insurers, and compares these to their market share. A high ratio of complaints or disputes compared to market share usually indicates either a less-than-adequate internal dispute-resolution process, especially for complex issues, or an underlying systemic or policy issue.

| 2015–16 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints | Percentage of Complaints | Disputes | Percentage of Disputes | Market Share | |

| ACA | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Australian Unity | 195 | 5.1% | 33 | 4.8% | 3.1% |

| BUPA | 834 | 21.7% | 196 | 28.6% | 26.8% |

| CBHS | 35 | 0.9% | 9 | 1.3% | 1.4% |

| CDH (Cessnock) | 2 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.1% |

| CUA | 70 | 1.8% | 17 | 2.5% | 0.6% |

| Defence | 26 | 0.7% | 6 | 0.9% | 1.8% |

| Doctors | 11 | 0.3% | 2 | 0.3% | 0.2% |

| GMHBA | 55 | 1.4% | 6 | 0.9% | 2.0% |

| Grand United Corporate | 17 | 0.4% | 5 | 0.7% | 0.4% |

| HBF | 125 | 3.3% | 21 | 3.1% | 7.4% |

| HCI | 1 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Health.com.au | 53 | 1.4% | 13 | 1.9% | 0.6% |

| Health Insurance Fund of Australia | 22 | 0.6% | 3 | 0.4% | 0.9% |

| HealthGuard (GMF/Central West) | 10 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.5% |

| Health-Partners | 13 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.6% |

| Hospitals Contribution Fund (HCF) | 406 | 10.6% | 66 | 9.6% | 10.5% |

| Latrobe | 16 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.7% |

| Medibank (AHM) | 1544 | 40.2% | 252 | 36.8% | 28.6% |

| Mildura | 1 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.2% |

| National Health Benefits (Onemedifund) | 1 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Navy | 2 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| NIB | 301 | 7.8% | 42 | 6.1% | 7.9% |

| Peoplecare | 6 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.5% |

| Phoenix | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.1% |

| Police | 1 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Queensland Country Health | 2 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.3% |

| Railway and Transport | 15 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.4% |

| Reserve | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.1% |

| St Lukes | 4 | 0.1% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.4% |

| Teachers Health | 47 | 1.2% | 6 | 0.9% | 2.1% |

| Teachers Union | 6 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.5% |

| Transport | 8 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| Westfund | 10 | 0.3% | 1 | 0.1% | 0.7% |

| Total | 3839 | 685 | |||

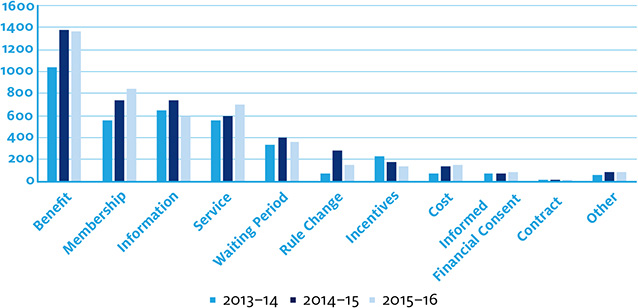

Complaint issues

BENEFITS

Complaints: 1359

Key issues:

- Hospital exclusions and restrictions

- General treatment (extras or ancillary benefits)

- Medical gaps

This was the largest area of complaint. The main issues of concern were hospital policies with unexpected exclusions and restrictions. Some basic and budget levels of hospital cover exclude or restrict services that many consumers assume are routine treatments or standard items. Delays in benefit payments and complaints about insurer rules that limited benefits were the other large areas of complaint.

CASE STUDY—Benefit: Hospital exclusion or restriction

Ayesha required surgery to her hand. The surgery was defined in the Medicare Benefits Schedule, under the 'Hand Operations' sub-group, as a 'carpal bone replacement or resection arthroplasty using adjacent tendon or other soft tissue including associated tendon transfer or realignment when performed'.

Initially, her health fund refused to cover the surgery because it considered the surgery to be 'joint replacement' which was an excluded service on her cover. However, this type of surgery does not involve the replacement of bone, but rather the removal of it.

On reviewing the information available to consumers about Ayesha's policy, the office noticed there was little guidance on what the insurer includes in the 'joint replacement' exclusion. However, it is a term used outside of its use by the health insurer; and our view is that the insurer should only use a definition of that term that is commonly understood in the community.

The office concluded that the surgery should be included in Ayesha's policy as it is not a joint replacement under any definition the office could find. After reviewing the case, the health fund agreed that the surgery was not 'joint replacement' and paid an appropriate benefit.

MEMBERSHIP

Complaints: 845

Key Issues:

- Policy/Membership Cancellation

- Clearance certificates

- Continuity of cover

Membership complaints typically involve policy administration issues, such as processing cancellations or payment of premium arrears. Delays in the provision of clearance certificates when transferring between health insurers is also a major cause of complaint.

CASE STUDY—Membership: arrears and cancellation

Kim joined his health fund in 2012 and had paid premiums by direct debit every month afterwards. In 2015 he required a hospital admission, but his booking was refused by the hospital as his membership appeared to have been cancelled.

On contacting the fund, Kim found that due to an administrative error, he had been undercharged for his premiums ever since joining in 2012. The fund had recently discovered this and corrected its records. But this had the effect of putting his policy into arrears and cancelling it.

The office concluded that Kim should not be adversely affected for an error the fund had made. The fund agreed to write off the arrears, bringing Kim's policy back up to date and allowing him to be covered for his hospital admission. However in future, Kim would need to pay the correct higher premium.

INFORMATION

Complaints: 599

Key issues:

- Verbal advice

- Lack of notification

Information complaints usually arise because of disputes or misunderstandings about verbal or written information provided by an insurer. Verbal advice is the cause of more complaints than any other sub-issue, and these can be particularly complex if the insurer has not kept a clear record or call recording of its interaction with the member.

CASE STUDY—Information: verbal advice

Adam realised he needed surgery which was not covered on his basic hospital policy. He called his health insurer to upgrade his policy, explaining he wanted to book a hospital admission within the next few months. The insurer told him that only a two month waiting period would apply, so Adam proceeded with the upgrade and booked a hospital admission in four months' time.

However, Adam was later advised that his treatment was actually subject to a 12 month waiting period for pre-existing conditions. This meant he was not covered for the surgery and he was asked to pay the full cost of the hospitalisation as he was about to be admitted.

On investigation, phone records confirmed that the health insurer had given incorrect advice about waiting periods when Adam upgraded his cover. The insurer had also encouraged Adam to upgrade to a more expensive policy to better cover hospital services.

Although Adam was made aware of the correct waiting periods for his cover before he was admitted, the office asked the insurer to consider a response to his complaint which accounted for the costs and inconvenience he had already incurred. The insurer instead decided to compensate Adam more than this and offered to honour the information it had provided him by paying the full hospital costs.

SERVICE

Complaints: 704

Key issues:

- General service issues

- Premium payment problems

Service issues are usually not the sole reason for complaints. The combination of unsatisfactory customer service, untimely responses to simple issues, and poor internal escalation processes can cause members to become more aggrieved and dissatisfied in their dealings with the insurer, until the service itself becomes a cause of complaint as well as the original issue.

WAITING PERIODS

Complaints: 363

Key Issues:

- Pre-existing condition disputes

- Compliance with PEC Best Practice Guidelines

Health insurers are able to apply a 12 month waiting period to new members if treatment is for a Pre-Existing Condition (PEC). Details about how the PEC waiting period is applied can be obtained by referring to our brochure 'Waiting Periods' and our factsheet on Pre-Existing Conditions, which are available at ombudsman.gov.au. PHIO's role in investigating complaints about the PEC waiting period is to ensure that the insurer has applied the waiting period correctly, and that the insurer and hospital have complied with the PEC Best Practice Guidelines.

RULE CHANGE

Complaints: 147

Key Issues:

- Detrimental changes to policies

- Adequate notice to consumers

Health insurers are permitted to make detrimental changes to their policies provided they give suitable advance warning to the affected members so they can change their cover or make other plans. In our view, a significant detrimental change to a hospital policy includes the exclusion or restriction of a previously included benefit, or the addition or increase of an excess or co-payment. It is important for insurers to communicate detrimental policy changes in clear and unambiguous language, without diluting the message by interspersing unrelated promotional material. Insurers should honour any pre-booked hospital admissions and ensure that benefits for patients currently in a 'course of treatment' continue for up to six months.

Figure 10: Complaint issues, previous three years

| Issue | Sub-issue | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit | Accident and emergency | 23 | 40 | 49 |

| Benefit | Accrued benefits | 4 | 9 | 3 |

| Benefit | Ambulance | 36 | 51 | 66 |

| Benefit | Amount | 58 | 63 | 67 |

| Benefit | Delay in payment | 147 | 154 | 142 |

| Benefit | Excess | 48 | 56 | 56 |

| Benefit | Gap—Hospital | 23 | 50 | 53 |

| Benefit | Gap—Medical | 38 | 131 | 151 |

| Benefit | General treatment (extras/ancillary) | 78 | 105 | 194 |

| Benefit | High cost drugs | 11 | 13 | 13 |

| Benefit | Hospital exclusion/restriction | 242 | 320 | 276 |

| Benefit | Insurer rule | 152 | 192 | 131 |

| Benefit | Limit reached | 28 | 24 | 14 |

| Benefit | New baby | 11 | 22 | 6 |

| Benefit | Non-health insurance | 19 | 8 | 9 |

| Benefit | Non-health insurance - overseas benefits | 8 | 8 | 3 |

| Benefit | Non-recognised other practitioner | 16 | 29 | 22 |

| Benefit | Non-recognised podiatry | 15 | 12 | 15 |

| Benefit | Other compensation | 10 | 16 | 14 |

| Benefit | Out of pocket not elsewhere covered | 12 | 9 | 15 |

| Benefit | Out of time | 15 | 19 | 15 |

| Benefit | Preferred provider schemes | 44 | 50 | 32 |

| Benefit | Prostheses | 10 | 9 | 11 |

| Benefit | Workers compensation | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Contract | Hospitals | 15 | 10 | 18 |

| Contract | Preferred provider schemes | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| Contract | Second tier default benefit | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Cost | Dual charging | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Cost | Rate increase | 78 | 132 | 147 |

| Incentives | Lifetime Health Cover | 163 | 156 | 121 |

| Incentives | Medicare Levy Surcharge | 21 | 12 | 11 |

| Incentives | Rebate | 39 | 13 | 9 |

| Incentives | Rebate tiers and surcharge changes | 5 | 1 | 2 |

| Information | Brochures and websites | 65 | 47 | 34 |

| Information | Lack of notification | 96 | 91 | 90 |

| Information | Oral advice | 410 | 522 | 430 |

| Information | Radio and television | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Information | Standard Information Statement | 5 | 8 | 6 |

| Information | Written advice | 66 | 64 | 38 |

| Informed Financial Consent | Doctors | 25 | 19 | 35 |

| Informed Financial Consent | Hospitals | 40 | 50 | 36 |

| Informed Financial Consent | Other | 7 | 1 | 13 |

| Membership | Adult dependants | 15 | 25 | 15 |

| Membership | Arrears | 93 | 144 | 106 |

| Membership | Authority over membership | 16 | 20 | 16 |

| Membership | Cancellation | 218 | 299 | 315 |

| Membership | Clearance certificates | 106 | 108 | 196 |

| Membership | Continuity | 72 | 100 | 114 |

| Membership | Rate and benefit protection | 5 | 19 | 32 |

| Membership | Suspension | 41 | 50 | 51 |

| Service | Customer service advice | 52 | 82 | 106 |

| Service | General service issues | 207 | 184 | 234 |

| Service | Premium payment problems | 141 | 184 | 211 |

| Service | Service delays | 164 | 155 | 153 |

| Waiting Period | Benefit limitation period | 5 | 6 | 1 |

| Waiting Period | General | 34 | 41 | 29 |

| Waiting Period | Obstetric | 47 | 49 | 51 |

| Waiting Period | Other | 22 | 19 | 14 |

| Waiting Period | Pre-existing conditions | 229 | 283 | 268 |

| Other | Access | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Other | Acute care certificates | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Other | Community rating | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | Complaint not elsewhere covered | 33 | 56 | 54 |

| Other | Confidentiality and privacy | 12 | 12 | 11 |

| Other | Demutualisation/sale of health insurers | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | Discrimination | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Other | Medibank sale | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | Non-English speaking background | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | Non-Medicare patient | 3 | 8 | 2 |

| Other | Private patient election | 10 | 3 | 6 |

| Other | Rule change | 72 | 281 | 147 |

Complaints about hospitals, doctors, brokers and others

Most complaints (88 per cent in 2015–16) are made about health insurers. However, complaints can also be made about providers including hospitals, doctors, health insurance brokers and other practitioners (such as dentists). There was an increase in complaints about verbal advice and incorrect information provided by health insurance brokers in 2015–16, which accounts for the increase in complaints from 34 to 75 complaints.

| 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | 40 | 38 | 47 |

| Health Practitioners | 53 | 29 | 58 |

| Health Insurance Brokers | 42 | 34 | 75 |

Overseas Visitors Health Cover

Each year, the Ombudsman helps consumers with complaints about Overseas Visitors Health Cover (OVHC) and Overseas Student Health Cover (OSHC) policies for visitors to Australia. These complaints are counted separately from complaints made against domestic health insurance policies.

Unlike Australians, who have the option of using the public Medicare system at no cost if they are not covered for a hospital treatment under their private health insurance policy, most visitors to Australia have no choice about whether they are treated at private patient rates.

The most common issue for overseas visitors included 74 complaints about policy cancellation and refunds, 40 complaints about the pre-existing condition waiting period and 38 complaints about delays in paying benefit payments.

| Insurer | 2013–14 | 2014–15 | 2015–16 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allianz (Lysaght Peoplecare) | 32 | 63 | 69 |

| Australian Unity | 11 | 25 | 12 |

| BUPA | 84 | 160 | 119 |

| HBF | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| HCF | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| HIF | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| Medibank Private (AHM) | 44 | 62 | 73 |

| NIB | 25 | 28 | 43 |

| Total | 200 | 347 | 321 |

NOTE: Figures for providers of cover for overseas visitors are not directly comparable, as market share data is not available. These figures show the number of complaints over time and it can be assumed market share numbers are relatively similar to those for domestic providers (see Table 5) and do not greatly change from year to year.

Complaint–handling procedures and categories

PHIO has three levels of complaint:

- Assisted Referrals for moderate complaints

- Grievances for moderate complaints that do not require a report or further investigation, and

- Disputes for high-level complaints where significant intervention is required.

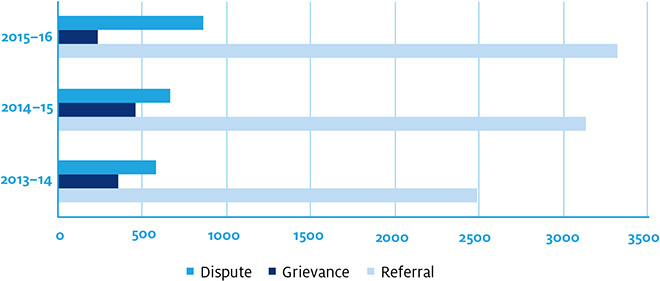

In 2015–16, 75 per cent of complaints were resolved as Assisted Referrals. In these instances, the Dispute Resolution Officer refers a complaint directly to a nominated representative of the insurer or service provider, on behalf of the complainant. This approach ensures a quicker turnaround time and our client satisfaction survey confirms that complainants have a high satisfaction rate with this method of resolution.