Part 4 - What we do

Social Services agencies and programs

Department of Human Services

In 2016–17, the Office received 13,832 complaints about Department of Human Services (DHS) programs. This represents a 30 per cent increase compared to the 10,662 received in 2015–16. This was largely due to an increase in the number of Centrelink complaints.

The department delivers a range of payments and services to millions of people across Australia.3 This includes services delivered through Centrelink and the Child Support system. Our Office acknowledges that it is inevitable that errors and delays will occur in an operation of this scale. However, we also recognise that this can affect some of the most vulnerable members of our community. As a result, our Office works with DHS to improve service delivery.

Table 4 – DHS complaint trends

| DHS Program | 2015–16 | 2016–17 | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Department of Human Services4 | 508 | 603 | 19% |

| Centrelink | 8,702 | 11,867 | 36% |

| Child Support | 1,452 | 1,362 | -6% |

| 10,662 | 13,832 | 30% |

DHS — Centrelink

CASE STUDY - Cessation of cheque payments

The 2015–16 Budget announced the phase-out of cheque payments for all Centrelink benefits from 1 January 2016. Payments would, in future, be made directly into customers' bank accounts or their payment nominee's bank accounts. DHS advised there would be no exceptions to this requirement.

Following complaints to our Office, we commenced an investigation. Our investigation revealed that as at 1 March 2016, 31 customers had payments suspended or cancelled due to not providing bank account details. Of these, 23 were Indigenous people living in remote communities, including 15 people living in residential aged care facilities. By 1 September 2016, payments had been restored to 25 customers and four were not receiving payments for reasons unrelated to the cessation of cheques. One customer was deceased. DHS explored a number of different payment options for one customer who did not want to operate a bank account.

We provided feedback to the department about a number of matters we consider could have been better managed, including:

- providing an adequate transition period, particularly for vulnerable customers

- using the correct legislative powers to avoid customers' payments being unlawfully suspended/cancelled

- proper planning and consideration of vulnerable customers from the outset

- responding to our investigation in a timely manner.

DHS took our feedback into account in a post implementation review of the measure and advised our feedback would be considered in the implementation of future program changes.

CASE STUDY - Payment of Newstart while participating in New Enterprise Incentive Scheme

Paul was receiving the newstart allowance when he started participating in the New Enterprise Incentive Scheme (NEIS). When the Department of Employment notified Centrelink that Paul was participating in the NEIS, Paul's newstart allowance was automatically cancelled. A person cannot usually receive newstart allowance and NEIS payments at the same time. However, Paul was eligible to receive partial payments of newstart allowance because he had a dependent child in his care.

DHS explained to us that, although a person may be eligible to receive a partial payment of newstart allowance while participating in the NEIS, their payments are automatically cancelled when Centrelink is notified they have commenced in the NEIS. Centrelink relied on the NEIS participant to contact them after the cancellation, so the newstart allowance could be restored. In Paul's case, his eligibility for a partial payment was not identified during his contact with Centrelink after commencing in NEIS, so the newstart allowance was not restored.

Following our investigation, DHS reviewed the decision to cancel Paul's newstart allowance and paid him arrears. DHS also reviewed its NEIS procedures and implemented processes to proactively identify and contact NEIS participants who may be eligible to receive a partial newstart allowance payment after they commence NEIS.

DHS delivers a range of social security and other payments and services to people through Centrelink. Complaints about Centrelink represent a substantial proportion of complaints to our Office. This is not surprising considering the size and complexity of its service delivery responsibilities.

In cases where a person is vulnerable or requires help to make a complaint about Centrelink to DHS, our Office continues to use a complaint transfer arrangement. This means the complaint is passed directly to DHS on the understanding that the complainant may come back to us if they have not been contacted within five working days or the complaint has not been resolved.

CASE STUDY - Compensation for poor advice

Ming was in receipt of disability support pension (DSP). Prior to departing Australia in May 2015, Ming contacted Centrelink on several occasions for advice about how overseas travel would affect her DSP. Ming told Centrelink her departure and return date and understood, from the advice provided, that her DSP would be restored when she returned to Australia. However, the advice did not align with the changes to the portability rules which had occurred in January that year, which reduced portability from six weeks absence to 28 days during a 12 month period.

As Ming was overseas for longer than four weeks, Centrelink correctly suspended her DSP and, as she remained overseas for a further 13 weeks, her DSP was then cancelled. Ming was unable to reclaim DSP because she is of age pension age. However, she is not eligible to receive age pension as she is not yet residentially qualified. Centrelink granted Ming a Widow Allowance instead, which is paid at a lower rate than DSP.

Ming claimed compensation from Centrelink, saying that its staff incorrectly advised she could have her payments restored if she returned within 19 weeks. She sought compensation for the difference between the Widow Allowance and DSP from the date of her return to Australia until the time she is able to claim age pension (which is paid at the same rate as DSP). Centrelink initially refused Ming's claim so, she approached our Office to make a complaint.

We investigated the complaint and asked DHS to reconsider the decision. In our view, Ming had provided Centrelink with her expected return date to Australia and it was therefore reasonable for Centrelink to have told her that her DSP would be cancelled prior to that date. DHS agreed that defective administration had occurred and made Ming an offer of compensation.

We also suggested that DHS consider revising the information provided to staff on DSP portability to prompt a discussion about the possibility of cancellation of DSP. DHS agreed to enhance Centrelink procedures to provide greater clarity for staff.

Significant Issues

Table 5 – Most common complaint issues5

| Issue | Number |

|---|---|

| Non-program/Service delivery | 2,065 |

| Newstart allowance | 1,962 |

| Disability support pension | 1,842 |

| Age Pension | 1,301 |

| Debt/Automated data matching | 849 |

The Office continued to monitor a number of issues of interest. During 2016–17, the most significant of these were:

- Centrelink Online Compliance Intervention system

- Centrelink debt recovery

- various aspects of the disability support pension (DSP)

- various aspects of Centrelink Authorised Review Officer reviews.

The Office has continued regular engagement with DHS staff to discuss and resolve systemic issues in Centrelink complaints, through scheduled quarterly meetings and ad hoc meetings by telephone or in person. Overall, the Office continues to monitor systemic issues arising and make recommendations both formally and informally in relation to strategic improvements.

Reports

Centrelink's automatic debt recovery system own motion investigation

In 2015–16, the Office liaised with DHS about improving customers' experience of Centrelink debts. DHS' management of Centrelink debt and the customer experience continued to be a focus for the Office in 2016–17. In July 2016, Centrelink launched a new online compliance intervention (OCI) system for raising and recovering debts. After the OCI system was implemented, the Office received many complaints from people who had incurred debts under the OCI. As a result, the Office considered the issue from a systemic perspective and, in April 2017, the Ombudsman published an investigation report into Centrelink's automated debt raising and recovery system.

The Office was satisfied the data matching process itself was unchanged, the debts raised by the OCI were accurate based on the information available to DHS at the time of decision, and it is reasonable for DHS to ask customers to explain discrepancies as a means of safeguarding welfare payment integrity. We found however, the OCI's initial messaging to customers, both through its letters and in the system itself, was unclear and did not include crucial information. Many of the OCI's implementation problems could have been mitigated through better project planning and risk management at the outset, such as more rigorous user testing, a more incremental rollout and better communication to staff and stakeholders.

We acknowledged the changes DHS had made to the OCI since the initial rollout, noting the changes had been positive and improved the usability and accessibility of the system. The Office also made recommendations about where further improvements could be made. DHS agreed with all of the recommendations.

DHS — Child Support

CASE STUDY - Failure to collect

Samira complained about the department's failure to collect child support. In September 2015, she had opted for DHS to collect child support on her behalf, estimating arrears at that time to be approximately $3,000. Samira provided DHS with information about the paying parent, Hamish's employment and banking details, but received no payments. When she complained to the department, she was told she needed to wait until Hamish lodged his tax return. Samira contacted our Office and we investigated her complaint.

DHS advised us that in October 2015 it had spoken with Hamish and he had provided his employer's details and asked for employer deductions to commence. DHS issued the employer with a notice under s 120 of the Child Support (Registration & Collection) Act 1988 (an inquiry notice). The employer responded to that notice advising that Hamish was not an employee. The department also made other inquiries but was unable to identify a collection avenue.

In December 2015, DHS received advice from an inquiry notice issued to a bank that it held several accounts for Hamish. One account included regular deposits made by the company Hamish had named as his employer. However, a second inquiry notice was not issued to Hamish's employer until April 2016.

In response to the second notice, the employer again responded advising that Hamish was not an employee. In late June 2016, DHS then telephoned the employer who confirmed that Hamish was in fact an employee. The company explained the previous confusion was due to the operation of its two separate payroll sections: one for casual employees and one for permanent employees, with neither section able to access both payroll systems. Employer deductions were set up for Hamish's child support liability and the arrears that had accrued.

DHS advised our Office that further follow-up action with the employer should have occurred at an earlier date. DHS should have followed up with the employer when it first received the information from the bank, about the payments made by the employer into Hamish's account, which contradicted the employer's response to the two inquiry notices issued.

DHS further advised that it had undertaken a review of its procedures in relation to information gathering powers. As a result, it had updated its guidelines to staff to include steps to conduct further investigations if a response to an inquiry notice does not align with other information held by the department.

DHS' Child Support program has a variety of functions relating to the transfer of payments between separated parents or other carers of eligible children. The Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about DHS' administration of child support. The number of complaints received about Child Support remained relatively stable in 2016–17.

The major emerging complaint themes about Child Support are collection and enforcement, assessment, change of assessments and customer service. This year our Office received briefings from DHS about child support activities and trials undertaken relating to intensive collection activities. The department advised it has expanded its Departure Prohibition Orders (DPO) and enforcement teams. Our Office will continue to liaise with the department on this issue and monitor related complaints.

Child Support system

The department advised that the implementation of the redesigned child support IT system has proven to be more complex and costly than originally estimated. Implementation was expected to be complete by 30 June 2017. We are monitoring the implementation closely for any adverse impact on child support customers. We will continue to engage with DHS and expect to receive regular updates from the department.

Department of Social Services

Our Office has oversight of the Department of Social Services (DSS), the agency responsible for social security legislation and policy.

Garnishee orders

The Social Security (Administration) Act 1999 requires that a 'saved amount' be left in a person's bank account to ensure they are able to support themselves. That amount is four weeks of income support payments, less the amount of those payments already spent. However, timing of garnishee orders and administrative processes can mean that, for some people, the saved amount is zero.

During 2016–17 our Office, in collaboration with the NSW Ombudsman, has facilitated engagement with key stakeholders about options to reduce the impact of garnishee orders on people already experiencing, or at risk of, severe financial hardship. This included:

- producing a joint paper on the issue, that was provided to DSS, the electronic Statutory Information and Garnishee Notices (eSIGN) Management Committee, the Financial Ombudsman Service and the states that contributed information to the paper, and

- leading a discussion at the Australia and New Zealand Ombudsman Alliance's Financial Hardship Interest Group meeting. Following that meeting, an options briefing was provided to the interest group for feedback.

We expect to meet with DSS on this issue in early 2017–18.

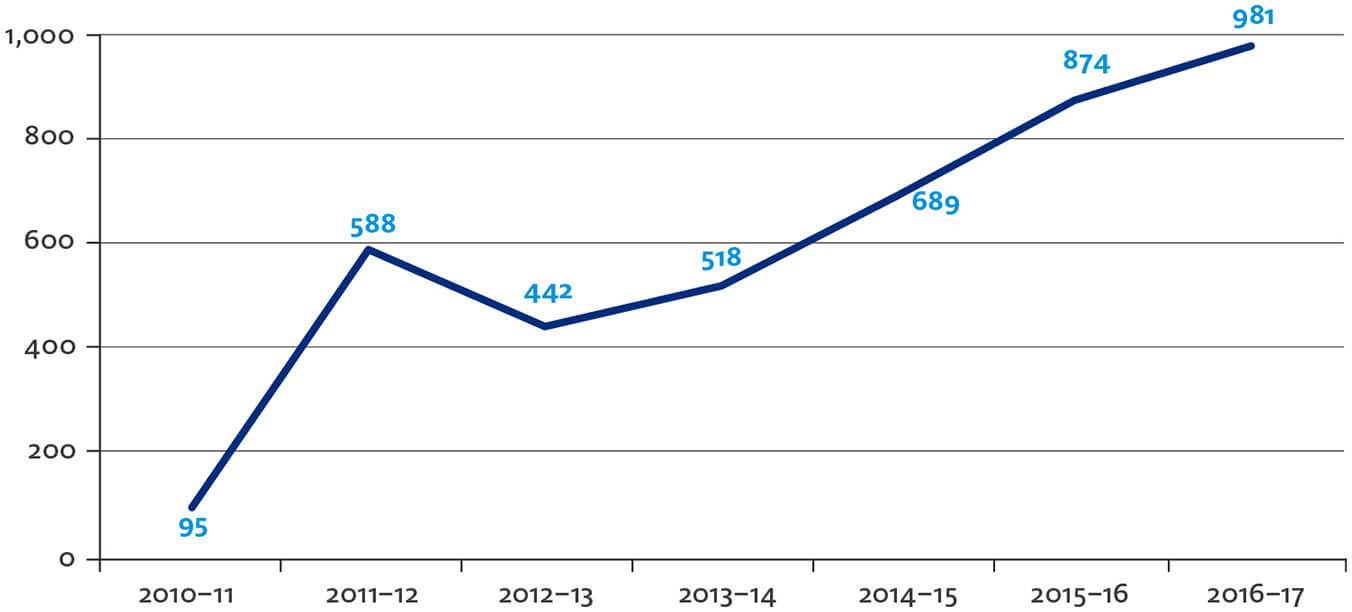

National Disability Insurance Agency

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) is the agency responsible for administering the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a Commonwealth scheme that provides funding to people with a permanent and significant disability to assist them to participate in everyday activities. People who are granted access to the NDIS are referred to as participants.

The NDIS was run on a trial basis in a number of trial sites from July 2013. In July 2016, the NDIA commenced gradually implementing the Scheme across the rest of Australia. The arrangements for entering the NDIS vary depending on the state or territory in which participants live.

The Commonwealth Ombudsman has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about the administrative actions and decisions of the NDIA, as well as complaints about organisations who are contracted to deliver services on behalf of the NDIA (for example, local area coordinators who conduct information gathering and pre-planning interviews).

Complaint trends

During 2016–17 we received 429 complaints about the NDIA, which is an increase on the 62 complaints we received during 2015–16. This escalation in complaints was not unexpected given that around 90,000 additional participants were due to access the Scheme during the year.

Complaints to our Office have covered many areas of the participant and provider experience, including:

- confusion about timeframes for receiving a plan after access to the Scheme is granted

- dissatisfaction with the mode and location of planning interviews

- delays in providers receiving payment for goods and services delivered

- difficulties using the participant and provider online portals

- delays in having quotes approved, particularly for home modifications and assistive technology

- confusion about how and when a participant may access NDIS funded supports

- confusion about NDIA's internal review and plan review arrangements

- lengthy delays in responding to complaints and requests for review.

The five most common complaint issues for this year are outlined in Table 6. These issues account for almost three quarters of all complaints about the NDIA.

Table 6 – Five most common complaint issues

| Issue | Number |

|---|---|

| Planning | 113 |

| Review | 92 |

| Complaints service | 55 |

| Access request | 51 |

| Service delivery | 45 |

Portal problems

In July 2016, the NDIA implemented new online 'portals' through which participants and providers can receive and send information to the NDIA. Many people and organisations reported to our Office and to the NDIA, problems they experienced using the portals. In some instances they also reported being unable to submit claims for payment for several months, resulting in financial hardship.

In response to the problems raised, the NDIA provided additional information to support providers and participants in lodging payment claims on the portal. This took the form of regular updates on the NDIA website and direct engagement with people and organisations who continued to experience problems.

The Department of Social Services (DSS) subsequently engaged PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) to undertake an audit of the implementation of the NDIA's new ICT system, including the online portals. PwC's report identified a number of areas in which the NDIA, its staff, participants and providers were not properly prepared for the change and made recommendations aimed at ensuring similar problems do not recur as the NDIS continues to be rolled out nationally.

In the second half of the year we received fewer complaints about problems with the portal, although some providers still report difficulties in obtaining adequate support from the NDIA to resolve technical issues as they arise. We continue to investigate those matters and to provide feedback to the NDIA as needed.

Reviews

Throughout this year we have received many complaints from participants and families who are having trouble with the NDIA's review processes. This includes:

- confusion about whether they should ask for an internal review of decision or a plan review

- what will be considered in a review

- whether they have the right to be involved in the review process

- the reasons for the eventual review decision

- whether they have any further review rights and, if so, how they pursue them.

The most common complaint about reviews relates to the time it takes for the NDIA to complete a review and the lack of acknowledgement or updates provided during the process.

In response to our investigations, the NDIA has acknowledged it receives large numbers of review requests and, at the time of publishing, does not have timeliness standards for acknowledging or completing reviews.

Access to robust, transparent and accessible review mechanisms is a key element of good public administration and is particularly important when an agency's decision is subject to significant discretion as is the case with NDIS plans. The NDIA's handling of reviews is likely to be a particular focus for our Office in 2017–18.

Major activities

Stakeholder engagement

Although complaints about the NDIA have increased during 2016–17, we are mindful that many people with a disability are reluctant to complain or may not feel able to do so without significant support. This year, to bolster our understanding of the experience of participants, families, providers and support organisations in engaging with the NDIS and the NDIA, we have travelled to a number of NDIS regions to meet with stakeholders. This included visits, public events and presentations in the Barwon, East Melbourne and North East Melbourne regions (VIC), Perth Hills region (WA), Barkly and Alice Springs regions (NT), Canberra (ACT), Townsville (QLD) and Western Sydney region (NSW).

These outreach activities also helped us build community awareness of our role in handling complaints about the NDIA.

Submissions

In 2016–17 we made submissions in response to:

- the Productivity Commission's inquiry into introducing competition and informed user choice into human services (February 2017)

- the Joint Standing Committee on the NDIS's inquiry into the provision of services under the NDIS to people with psychosocial disabilities related to a mental health condition (February 2017)

- the Productivity Commission's inquiry into the costs of the NDIS (March 2017)

- the Department of Social Services' discussion paper on an NDIS code of conduct (June 2017).

Quality and safeguarding arrangements for the NDIS

In February 2017 the Minister for Social Services announced the release of a Quality and Safeguarding Framework for the NDIS. The Framework was the result of consultation with the Australian community, including our Office, and outlines the arrangements for ensuring the quality and safety of NDIS funded services.

In the 2017 Budget, the government announced it will implement an NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Commission that will have responsibility for registration and oversight of NDIS funded services. It will also have responsibility for taking complaints about these services. The Commission will commence operations in July 2018 and will gradually assume the responsibilities of the state and territory disability complaints bodies who currently have jurisdiction over NDIS funded (and other disability) services.

We currently work closely with the state and territory oversight bodies to share information about our respective roles in handling complaints about the NDIS and, when needed, jointly investigate complaints. We will continue to do so during 2017–18 and as the state and territory bodies transfer their responsibility to the Commission in the following years.

Our Office will also have jurisdiction to handle complaints about the Commission once it is established.

CASE STUDY - Communication about access and planning

In January 2017, Jennifer complained to our Office about the delay her son Bailey experienced in receiving an NDIS plan. Jennifer explained that Bailey had received a letter from the NDIA in November 2016 which indicated he had been accepted into the NDIS and the NDIA would contact him soon to make arrangements for a plan.

Jennifer explained she had contacted the NDIA on several occasions since Bailey received the letter, at which time the NDIA told her the area Bailey lives in would not commence implementation until November 2017. This date was twelve months after Bailey was accepted into the Scheme, and Jennifer said she did not know how Bailey would be supported in the meantime.

In response to our investigation, the NDIA:

- advised the letter sent to Bailey was a generic one with the purpose of advising him that he had been granted access to the NDIS

- acknowledged the letter had caused confusion by indicating Bailey would be contacted 'shortly' to commence planning, despite the fact his local area was almost a year away from commencing rollout

- advised it was progressing changes to its letters to remove the reference to contact occurring 'shortly'

- advised it had sought to better manage expectations by amending its arrangements for assessing access requests to ensure that, unless someone meets the priority access criteria, prospective participants are only able to seek and be granted access up to six months in advance of their local area commencing rollout.

In response to comments we made at the conclusion of our investigation, the NDIA also undertook to include clear advice in access decision letters to participants and families that, until the NDIS commences in their local area, the relevant state or territory government remains responsible for providing disability services to people in their jurisdiction.

CASE STUDY - Communication about participant pathway

Deanne complained to us about the NDIA's refusal to reimburse her son's speech therapist for services they provided to him.

Deanne explained that she received a letter from the NDIA, which advised that her son had been granted access to the NDIS. Shortly after receiving the NDIA's letter, and understanding her son was now able to access NDIS funds, she booked appointments for him with a speech therapist. When the speech therapist attempted to make a claim with the NDIA for the services they provided to Deanne's son, the claim was refused because he did not yet have an NDIS plan. Deanne complained that the NDIA's letter had not made it clear she must wait until her son had a plan before she could purchase supports for him.

Based on the information the NDIA provided in response to our investigation, we were satisfied the NDIA was not able to reimburse the speech therapist for the services they provided to Deanne's son prior to his support plan being approved. However, we suggested the NDIA update its written communications to participants to make it clear that, although they may have been granted access to the Scheme, participants cannot access NDIS funded supports until they have an approved NDIS plan. In its response, the NDIA advised it is working to strengthen the information in its letters to make it clearer to participants when they can commence accessing NDIS-funded supports.

Department of Employment

The Department of Employment has responsibility for the national policies and programs assisting Australians to find employment and work in a safe, fair and productive workplace.

Complaints in 2016–17

During 2016–17, we received 382 complaints about the Department of Employment, which is significantly less than the 499 complaints received in 2015–16. In 2016–17 our Office investigated and finalised 40 complaints.

Within our Office, all complaints about employment service providers are recorded against the agency with the oversight responsibility for the program complained about. This means that complaints concerning the Department of Employment's National Customer Service Line are directed to the agency that has policy responsibility for the employment program. For example, complaints about Disability Employment Services providers are recorded as complaints about the Department of Social Services, complaints about jobactive providers are recorded as complaints about the Department of Employment, and complaints about Community Development Programme providers are recorded as complaints about the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C).

Most complaints received about the Department of Employment during 2016–17 concerned the actions of jobactive providers and the National Customer Service Line. The key issues in complaints about jobactive providers included the standard of service provided, job support services provided, quality of complaint-handling and job seekers wanting to change provider.

We have continued to engage with the Department of Employment, and have agreed to formal liaison meetings every six months. In 2016–17, the Department of Employment provided a briefing to our office about the National Customer Service Line.

Clarification of comments in our 2015–16 Annual Report

The Commonwealth Ombudsman's 2015–16 Annual Report included comments that the jobactive Deed provided no effective way for the Department of Employment to direct that efforts be more targeted and focused on participants' prior experience. Following consultation with the Department of Employment and further examination of the Deed and relevant guidelines, we recognise the statement was not correct.

We also acknowledge that comments made about receipt and investigation of complaints where it appeared that manifestly unreasonable referrals of job seekers to activities had occurred were not substantiated by the complaints we received in the relevant period.

We will continue to monitor any trends and systemic issues that arise in complaints we receive about the Department of Employment, as we do for all agencies within our jurisdiction.

INDIGENOUS

CASE STUDY - Indigenous language interpreters

Holly is an Aboriginal non-English speaking woman. DHS conducted a tape recorded (prosecution) interview with her without the assistance of an Indigenous language interpreter. We reviewed a transcript of the interview and asked DHS a series of questions about its handling of the interview.

DHS acknowledged, on review of the transcript, it would have been appropriate to have engaged an interpreter for Holly, rescheduled the interview to allow her to get legal advice, and for DHS to have arranged an accredited interpreter.

In response to contact from our Office, DHS said it would make the e-learning package 'Indigenous Interpreters' mandatory for investigators.

This year saw the completion of the Office's Indigenous Accessibility Review, undertaken by Aboriginal communications company, Gilimbaa Pty Ltd. This review involved Gilimbaa considering all elements of the Office's operations, to provide guidance about how we can ensure our services are accessible to Indigenous people irrespective of where they live in Australia. This project also aimed to enhance our capacity to handle Indigenous complaints effectively and appropriately, and contribute to a 'no wrong door' approach for Indigenous complaints.

CASE STUDY - Centrelink debt and use of Indigenous language interpreters

Maggie is an Aboriginal non-English speaking woman. She is also illiterate and innumerate. She lives in a remote town several hours from the nearest Department of Human Services (DHS) Customer Service Centre and has no reliable access to telephone and internet services.

Maggie incurred 23 small debts between November 2011 and August 2015. She had difficulty declaring her income correctly and consequently her local Centrelink office had made arrangements for her employer to email her payslips to DHS each fortnight. However, while Maggie's employment pay period and Centrelink reporting day were aligned to Fridays, her payslips were not generally available from her employer until the following Thursday. She had her reporting requirements repeatedly explained to her in English and her language needs were not noted in her record.

This complaint was included in our own motion report into the accessibility of Indigenous language interpreters to highlight issues around staff training and awareness of the need to use interpreters (rather than family members) and the importance of ensuring that a customer's record accurately identifies their first language.

In Maggie's case, DHS identified four local servicing solutions that could be offered to improve her ability to accurately declare her earnings. While not all of these options are scalable nationally, the department indicated it would conduct an immediate review of key operational materials to better clarify available options to help people calculate and declare employment income correctly. In the medium to long term, DHS will explore opportunities to define clear referral pathways for claimants who have continuing difficulty declaring their earnings, so that individually tailored solutions can be found.

In the course of this complaint, DHS also agreed with our Office that there is value in authorised review officers undertaking refresher training in applying debt waivers and using Indigenous language interpreters.

The review focused on three key areas:

- communication and engagement with Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander audiences

- an enhanced internal strategy for handling Indigenous complaints

- staff training and development to support implementation activity across the Office.

Implementation of the report and recommendations will be a priority for the Office in 2017–18.

Reconciliation Action Plan

During the year we started working on our second Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP). This is being developed by a working group of staff from across the Office.

The new RAP will be underpinned by the actions from the accessibility review. It will focus on enhancing relationships with our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stakeholders, implementing programs for cultural learning, employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and supplier diversity.

The RAP is a vital part of our continuing commitment to an Office that is culturally aware, respectful, collaborative, inclusive and trusted.

Events

The highlight of our National Reconciliation Week activities was an Aboriginal Art Workshop held in Canberra which brought together staff from each state.

The Office held a stall at the Indigenous Expo at Yarramundi markets at the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cultural Centre in Canberra in May 2017.

We coordinated a number of Community Round Tables and stakeholder events throughout 2016–17. Round Tables provide an opportunity for local legal, community and support organisations to talk to us about issues they and their clients are experiencing with ACT or Australian Government agencies. They also allow us to talk with stakeholders about the work we do.

Outreach

As part of our outreach program, we met with a number of Indigenous communities in the Alice Springs and Tennant Creek areas of the Northern Territory during 2016–17. These meetings provided valuable insights into a range of issues, including the use of Indigenous Language Interpreters, the administration of the Community Development Programme, the roll-out of the National Disability Insurance Scheme to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and issues related to the delivery of Centrelink services in remote communities.

From 14 May to 24 June, the Office participated in the Jawun program, which partners with the Australian Public Service and the corporate sector to develop greater self-sufficiency for Indigenous people and their communities. Jawun aims to share skills and knowledge to build the capacity of Indigenous people and organisations and increase cultural awareness.

Community of Practice

We held our second Commonwealth Government Indigenous Complaint-Handling Community of Practice event in Canberra in April. Thirty five staff from 10 Commonwealth agencies participated. The theme for the symposium: Engaging meaningfully with Indigenous Australians using digital media—opportunities and challenges for government..

The highlights included:

- Aunty Violet Sheridan opened the event with a welcome to country on behalf of the Ngunnawal people

- Professor Peter Radoll, Dean of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership and Strategy at the University of Canberra, delivered a keynote address about how Indigenous Australians use media

- Ten speakers across two panels spoke about opportunities, challenges and lessons learned by business, welfare, youth and government sectors. These discussions also challenged the negative discourse relating to Indigenous issues and the 'narrative of the downtrodden'.

Feedback from the symposium indicated it was a successful event that provided valuable insights into the complexities, challenges and opportunities for government agencies using these mediums to engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Working groups

Right to Complain working group and ANZOA Indigenous Complaint-Handling interest group

During 2016–17 the Office coordinated an Indigenous Right to Complain working group, comprising representatives from a number of agencies we oversee and also facilitated the Australian and New Zealand Ombudsman Association's (ANZOA) Indigenous Complaint-Handling interest group.

The purpose of these groups was to identify and share best practice in Indigenous complaint-handling and promote a 'no-wrong-door' approach across sectors.

Issues of interest

We continue to monitor a number of important issues of interest. This year, the most significant of these were:

- use of Indigenous language interpreters

- accessibility of disability support pension for remote Indigenous people

- Indigenous Centrelink debt

- income management and the cashless debit card trials

- Centrelink call wait times in remote areas

- Centrelink Agent Services

- administration of the ABSTUDY program.

Reports and own motion reports

Disability support pension report

In December 2016, the Ombudsman published an investigation report into the accessibility of the disability support pension (DSP) for remote Indigenous Australians. The investigation analysed complaints from remote Indigenous DSP claimants and included case studies which illustrate the challenges Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples face in the DSP claim process. For example, barriers to accessing supporting medical evidence and lack of access to face-to-face job capacity assessments.

The report analysed areas where the Department of Human Services' claim process could be improved to address these barriers. It made practical recommendations about the job capacity and medical assessment processes, including the conduct of assessments, flow of information to and from health professionals, and communication with claimants about DSP 'program of support' requirements.

During the investigation of these complaints and the production of this report, DHS made a number of improvements to the claim process for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander customers. We recommended that DHS establishes a framework to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of these changes.

Indigenous interpreters own motion

In April 2016, the Ombudsman approved an own motion investigation into the accessibility and use of Indigenous language interpreters spanning 47 government agencies.

The investigation considered the performance of government agencies against the recommendations of our 2011 Report 'Talking in Language: Indigenous language interpreters and government communication 05/2011'.

The findings of the investigation were published in a formal report. While there has been some progress since 2011, communication between government and Indigenous non-English speakers continues to be undermined by major barriers to accessing Indigenous language interpreters.

Our investigation found that accessibility challenges go beyond the ability of any one agency to address, and a coordinated whole of government response is required. After the commencement of the investigation, the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) reconvened an Inter-Departmental Committee for Indigenous Interpreters.

Our report recommended that PM&C work with the states and territories to prioritise finalisation and adoption of a National Framework for Indigenous Interpreters and further investment in programs and trials that have delivered results. It recommended that all agencies consider how their policy settings and administrative arrangements might be developed or better oriented to address the issues raised in the report and proposed best practice principles for the use of Indigenous language interpreters.

Postal Industry Ombudsman

Overview

The Postal Industry Ombudsman (PIO) role of the Commonwealth Ombudsman was established in 2006 to provide an industry ombudsman service for postal operators and their customers. This year marks our 10 year anniversary.

The Office investigates complaints about postal and similar services provided by Australia Post and Private Postal Operators (PPOs). We also investigate complaints about administrative actions and decisions taken by Australia Post.

Australia Post is a mandatory member of the PIO Scheme, while PPOs may choose to voluntarily register. As at 30 June 2017, there were six voluntary members on the Private Postal Operator Register.

Statistics

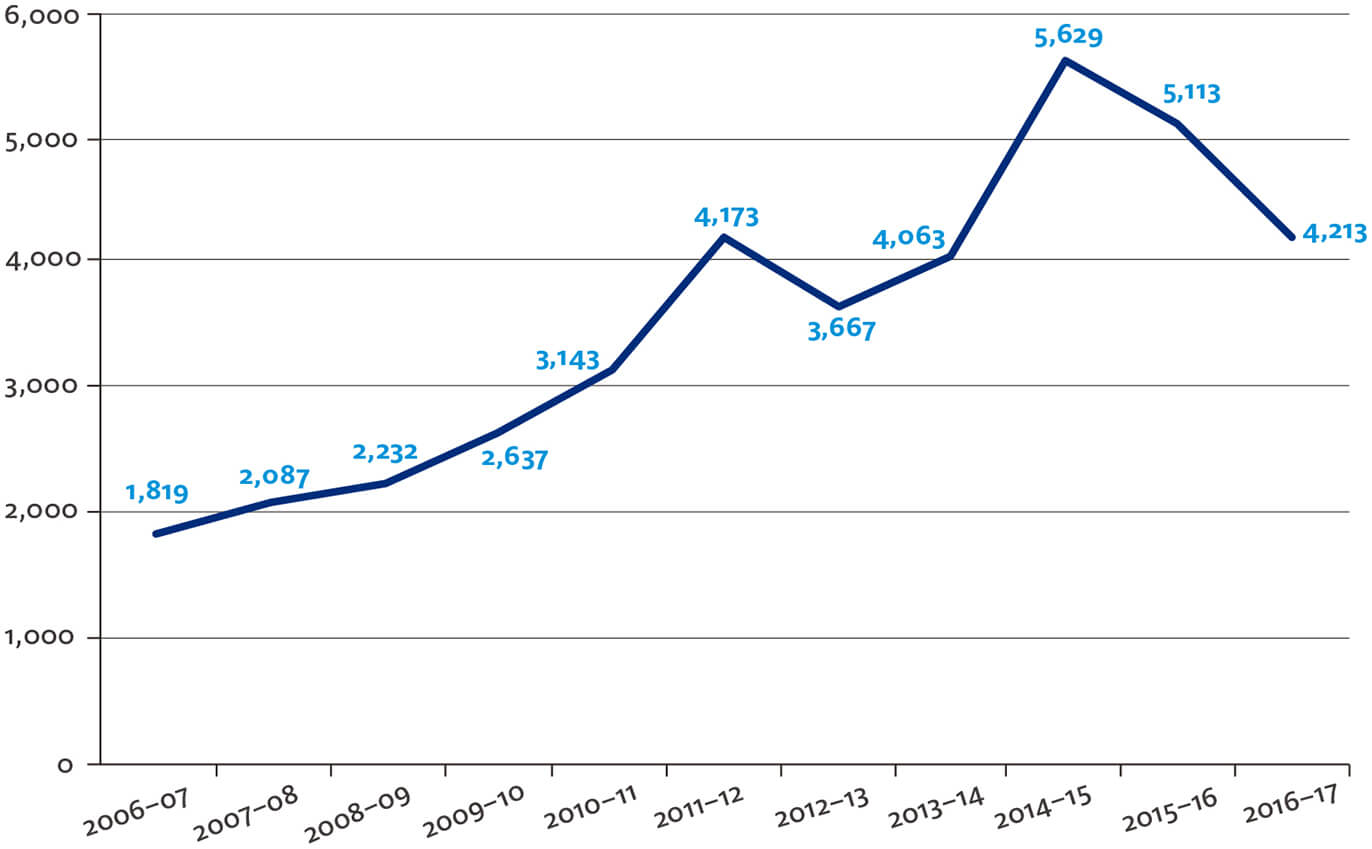

In 2016–17, we received 4,213 complaints, representing an 18 per cent decrease from the previous financial year.

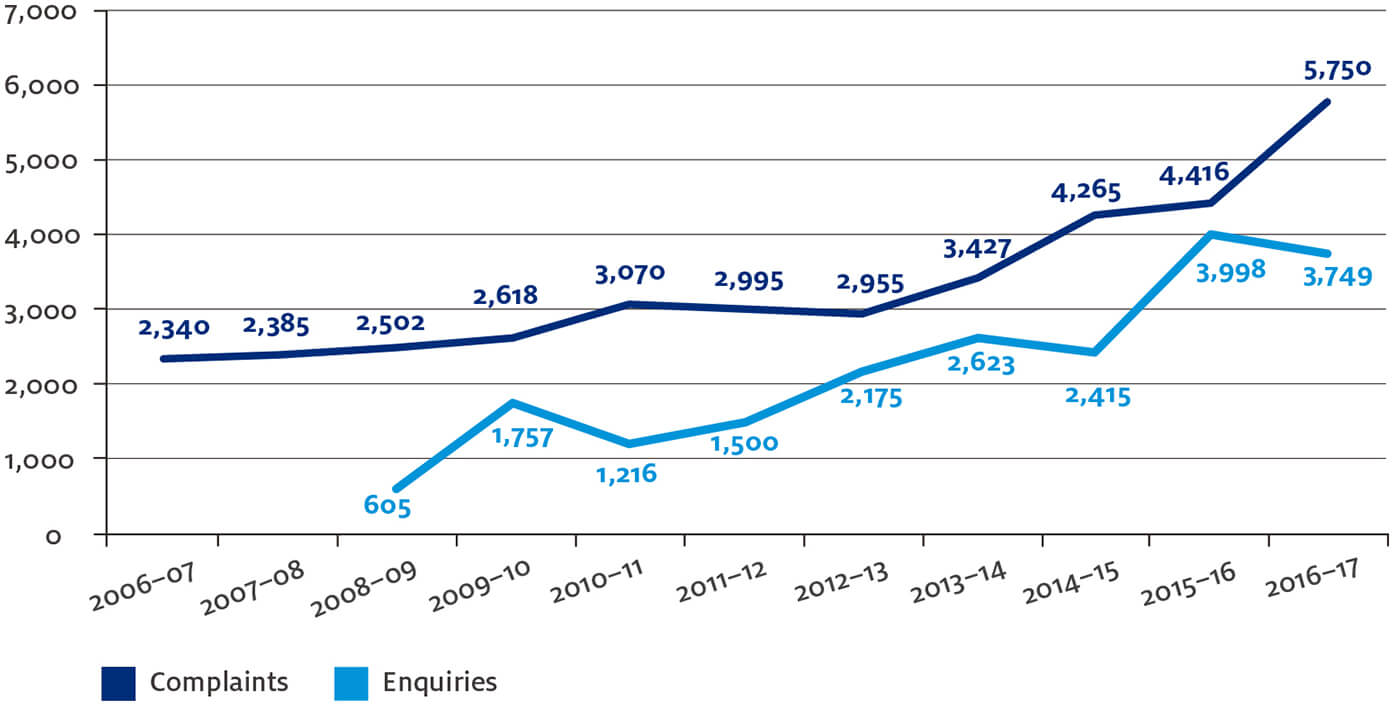

Figure 2 – PIO complaint numbers: 2006–07 to 2016–17

Most of the complaints (4203) we received were about Australia Post (including Startrack), the largest provider of postal services in Australia.

A nominal number of complaints (10) were received regarding the other PPOs.

CASE STUDY - International parcel returned to sender

Sally posted an International Express Post parcel from Australia to her son in Europe who said he never received the parcel. She contacted her local Post Office about the parcel and was told the tracking showed the parcel had been delivered to the European address but had been returned to sender. Ten weeks later the parcel was returned to Sally who confirmed that the correct address and details were used. Sally lodged a complaint about the lost parcel and requested a refund of the postage costs. She was not satisfied with the delay in Australia Post finalising her complaint and complained to us.

As a result of our investigation, Australia Post apologised for the delay in handling the complaint and acknowledged some errors had occurred and compensated Sally for the cost of postage.6

Significant issues

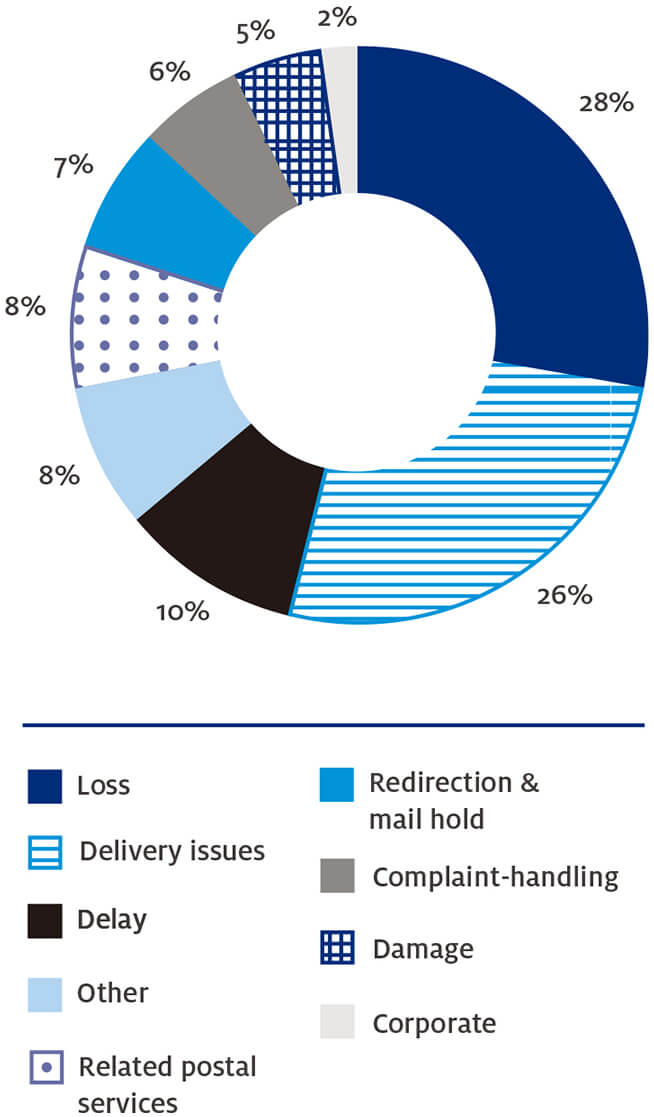

We have observed an increase in complaints about parcels and a decrease in complaints about letters. This is consistent with Australia Post's reports of increases in domestic parcel deliveries and a reduction in the demand for its reserved letter services.7 Around 90 per cent of complaints about Australia Post related to non-reserved services such as parcel delivery, express and premium services and retail services. The remainder related to reserved services predominantly concerning the delivery of regular letters.

Complaints about loss, delivery and delay continue to generate significant numbers of complaints to our Office, with the main focus on particular delivery processes like 'Safe drop' and carding.

Figure 3 – Australia Post complaint issues in 2016–17

CASE STUDY - Disputed delivery

Ruprecht was expecting a parcel however it failed to arrive. He contacted the sender who advised the tracking showed the parcel had been delivered. He enquired with Australia Post parcels who informed him the parcel had been 'Safe dropped' and no further investigation was warranted. Ruprecht complained to Australia Post on the basis that his property was close to the road and there was no safe place to leave the parcel that was not in view of passers-by. Australia Post declined to investigate the matter further.

Ruprecht contacted our Office. We conducted an investigation into the complaint and as a result of that investigation, Australia Post discovered the parcel was delivered to the wrong address and agreed to cover the cost to replace the item and the postage costs.

Outcomes

The Office values the complaints we receive from the community about postal services and uses this feedback to work with Australia Post and help it improve its customer service.

On 1 July 2016, we replaced our 'Second Chance Transfer' process which has been in operation since 2012 with a new short investigation process focusing on the rapid resolution of postal disputes.

In 2016–17, we finalised 881 investigations—and we have continued to provide feedback to Australia Post following our investigations. One of the factors that contributed to the rise in investigations was the replacement of the transfer process with a short investigation process. The Office continues to explore methods to improve its operational efficiency and effectiveness.

Some key investigative outcomes this year have been:

- the faster resolution of complaints with the average time taken to finalise investigations reducing by over one third on last year

- the provision of better explanations by our Office and by Australia Post

- apologies provided by Australia Post to complainants

- the provision of financial remedies including compensation, refunds, goodwill payments and in-kind services

- feedback to Australia Post staff.

Not all complaints need to be investigated. Almost 30 per cent of complainants who contacted us had not first complained to the postal operator, which is the fastest and most effective way to address the complaint. Some complaints are resolved before we commence an investigation.

CASE STUDY - Matter resolved without need for investigation

Isadora contacted us because she was not satisfied with the way Australia Post responded to her complaint. She advised that Express Post parcels were always delivered but general parcels were not delivered, leaving a card for later collection at the Post Office even though she was home each time. She complained to Australia Post over the phone and at the Post Office but nothing appeared to change.

Before we could investigate, Isadora contacted us and withdrew her complaint because Australia Post had arranged for a manager to attend her home and address the matters raised in her complaint. Australia Post advised that it would discuss the issue with the driver and ensure that it does not happen again. Isadora advised she was happy with this outcome.

Commencement of review of Australia Post

In June 2017, we commenced a review of three historical PIO reports regarding Australia Post to address the issues we continue to receive regarding delivery, loss and damage, and compensation.8 The review will consider Australia Post's implementation of the recommendations and observations in the previous reports in addition to the other measures it has introduced to address these issues.

The review will look at the impact of these measures on current complaint numbers and common issues and is scheduled for release in late 2017.

Additional reporting under s 19X of the Act

It is a requirement of the Office to report on the following in regard to s 19X of the Act:

- The Postal Industry Ombudsman made no requirements under section 9 during 2016–17.

- There were no occasions where a complaint—or part of a complaint—was transferred from the Postal Industry Ombudsman to the Commonwealth Ombudsman under subsection 19N (3).

- The Postal Industry Ombudsman made no reports during the year under section 19V.

Immigration Ombudsman

Overview

The Office investigates complaints about the Department of Immigration and Border Protection including the Australian Border Force (the department), and we review systemic issues that can arise from complaints.

The complaints can be about general immigration matters like visa processing delays, or detention-related issues, and complaints about Customs' functions, such as delays in releasing inspected international cargo. We also monitor the department's compliance activities and detention centres. Monitoring of visa compliance activities involves looking at the issuing of warrants that allow departmental officers to enter premises where there is reasonable cause to believe that a person is residing unlawfully in Australia. We regularly inspect immigration detention facilities. We also have a statutory reporting function to report to the Minister on people who have been detained for more than two years.

Complaints

In 2016–17 we received 2,071 complaints about the department, compared with 2,341 in 2015–16, a decrease of 11 per cent. Of these, we investigated 438 (21 per cent). The Office generally declines to investigate when:

- the matter is out of jurisdiction (for instance it might relate to the actions of a Minister)

- the complainant has not approached the agency first (we generally give agencies an opportunity to address matters)

- the matter complained of is more than 12 months old

- there is no prospect of getting a remedy for the complainant.

Common themes for detention complaints are similar to those in previous years: loss or damage to detainees' property, placement within the detention network and medical issues such as access to specialist care, appropriate treatment for injuries and illness, and delays in the processing of claims for asylum.

Complaints about delays in granting citizenship have continued to increase. We sought a briefing from the department on this issue in 2015–16 and we were advised that the department is taking actions to minimise the delay for people applying for citizenship, taking into account the need to ensure that appropriate attention is given to identity and security matters. We continue to monitor this issue.

Investigations

Delays in the processing of permanent partner visa applications is another issue of interest for the Office. We have observed a significant increase in processing times for onshore partner visa applications despite a decline in the overall number of applications. The department has advised that the impact of staffing reductions, introduction of mandatory police checks for sponsors since 18 November 2016, and managing visa grants within the migration program planning levels, have contributed to the average processing time exceeding 12 months. In turn, this has resulted in increased enquiries and complaints from applicants trying to find out the status of their visa application.

There have been delays in processing visas for those partners and families who are sponsored by former irregular maritime arrivals. Under Ministerial Direction 72, the department has been directed to move these to the lowest processing priority.

Own motion investigations

The Ombudsman released three reports on own motion investigations about immigration in 2016–17:

Report 07/2016 (published December 2016) 'The administration of people who have had their Bridging Visa cancelled due to criminal charges or convictions and are held in immigration detention'

We commenced this investigation in response to complaints and stakeholder concerns raised with us about the cohort of people who have had their Bridging visa cancelled on the basis of a criminal charge, conviction, or the possibility that the person poses a threat to the Australian community. The Minister can (but is not required to) cancel a person's Bridging visa if that person has been convicted or charged with a criminal offence, or there is a possibility that the person poses a threat to the Australian community.

When a person's visa is cancelled, they will be liable for immigration detention if they remain in Australia unlawfully. If they are considered to be an irregular maritime arrival, the law prohibits them from lodging any further visa application without the personal intervention of the Minister. Intervention by the Minister is facilitated by departmental identification of cases that fit the guidelines for referral to the Minister.

We were concerned that people were being detained based on criminal charges:

- where the charges are later withdrawn, and

- the person is not promptly released from immigration detention once the criminal charges against them have been resolved.

The report identified a case management system that is struggling to adequately manage the volume of people in immigration detention. This, coupled with the mandatory requirement for ministerial intervention in many cases before any progress toward status resolution can be made, means people are remaining in detention longer than is desirable.

The report cites examples of people who were not prioritised for consideration for release from detention after their criminal charges were resolved and who have remained in immigration detention.

The report's recommendations encouraged the department to:

- allow the person who is the subject of a Notice of Intent to Consider Cancellation of a visa, adequate time and resources to seek advice

- provide written notice of decisions for Bridging visa cancellations in the person's own language including the reasons for the decision, review rights, the timeframe for seeking review, details on how to seek a review and how the department can facilitate contact with the tribunal and a legal representative

- not transfer a person between detention facilities until the statutory time to lodge an appeal has expired (two days), and ensure that a person has the resources, such as access to the internet, in order to request a review

- promptly seek the Minister's intervention to grant a visa where a decision is set-aside by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal but the person's visa has expired, and identify all such cases and brief the Minister

- ensure the case management and escalation framework supports timely referral of cases to the Minister that meet the referral guidelines.

In response, the department suggested that the application of Direction 63 has delivered the policy intent expected by government. The department did not accept the recommendations and provided a substantial response that is attached to the published report, which includes responses specific to each recommendation.

Our Office notes in particular, the department's overall comment that the Australian Border Force (ABF) has matured since the investigation was undertaken, with increasing skill levels as well as broader familiarity with legislative and policy requirements. The department acknowledged some capability gaps around cancellations since the integration of ABF and the department—which it indicated it was addressing—and recognised a need for further training of officers so that cancellation decisions can demonstrate clear consideration of Ministerial Direction 63 and clear assessment against cancellation grounds.

Report 08/2016 (published December 2016) 'The administration of section 501 of the Migration Act 1958'

The Ombudsman's Office has a long standing interest in the administration of s 501 of the Migration Act 1958 and in 2006 completed an own motion investigation, Administration of s 501 of the Migration Act 1958 as it applies to long term residents. That report was critical of the quality of information provided to the decision maker when considering visa cancellations. In particular the Office was concerned that the then Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs (DIMA) did not always provide the Minister with all relevant information, especially mitigating information, about long-term Australian residents.

Section 501 was amended on 11 December 2014 by the Migration Amendment (Character and General Visa Cancellation) Bill 2014. Changes included the insertion of s 501(3A) that requires mandatory cancellation of visas in certain circumstances. The number of visas cancelled under s 501 increased from 76 in 2013–14 to 983 in 2015–16.

Complaints to our Office, observations from our compliance monitoring of the department's use of intrusive powers and our inspection of immigration detention facilities raised concerns about the following aspects of the administration of s 501:

- the length of time a person spends in immigration detention while awaiting a revocation request outcome

- notification of a visa cancellation shortly before release from prison

- the impact of prolonged and interstate detention on detainees and their families

- the impact on immigration compliance operations and the detention network.

The department aims for cancellations of visas under s 501 to occur well before the estimated date of release from prison so that any revocation process can be finalised while in prison.

Our report concluded that there was:

- a backlog in identifying people subject to a possible s 501 cancellation which prevents the cancellation/revocation process from being considered prior to the end of a prisoner's custodial sentence

- a delay in deciding the outcome of revocation requests. This leads to former prisoners spending prolonged periods in immigration detention.

The Ombudsman's recommendations focus on:

- improving the administration of s 501 by trying to have the cancellation and revocations processes completed prior to the end of a prisoner's sentence, and

- prioritising cases impacting upon children.

The department accepted the Office's recommendations and has provided the Office with information about the initial measures it has taken to implement these.

Report 01/2017 (published January 2017) 'Investigation into the processing of asylum seekers who arrived on the SIEV Lambeth in April 2013'

In July 2015 our Office identified apparent errors in the assessment of individuals' claims for protection as part of its statutory reporting obligations under s 486 of the Migration Act 1958 to report on the circumstances of people who have been detained for more than two years.

Some of the passengers of the SIEV Lambeth were taken aboard an Australian Customs vessel and sailed through the waters of Ashmore Lagoon (a place excised from the Australian migration zone) for the purpose of rendering them as offshore arrivals and subject to the s 46A bar. Other passengers were taken directly to Darwin for medical treatment. We sought information from the department to clarify our understanding of this situation. The department took an unreasonably long time to respond and some of the information was incomplete, or contradictory. The Ombudsman commenced an own motion investigation in December 2015.

The investigation looked at the processing of irregular maritime arrivals between 13 August 2012 and 20 May 2013 (the Australian mainland was excised from the migration zone on 20 May 2013).

We discovered that:

- not all of the of people were subject to the s 46A bar

- relevant information was not recorded in the department's records.

Overall, we were satisfied that the department's processing of these passengers reflected the legislation in force at the time. The Ombudsman made two recommendations:

- That the department review the information that was recorded for people arriving on board SIEV Lambeth and identify any shortcomings in the scope and manner of the information recorded and ensure that all relevant information is available to all departmental officers who have a reasonable need for access to it.

- That the department consider any learnings from this review and apply these to its systems more broadly where appropriate.

The department accepted both recommendations and has provided a response outlining the initial measures taken to implement the recommendations. The department has also completed a review of all persons who arrived between 13 August 2012 and 20 May 2013 and is considering the review findings.

The full reports can be found at ombudsman.gov.au/publications/investigation-reports

Liaison and stakeholder engagement

We meet with the department regularly to discuss systemic issues and matters of interest. We also receive briefings from the department where we request detailed information on an issue.

In May 2017, the department provided its first quarterly update to the Ombudsman's Office on the implementation of recommendations made in own motion investigations. Following consultation with our Office, the department is actively tracking the implementation of recommendations made in the Ombudsman's reports with progress on implementation reviewed by the department's audit committee.

We have a program of community roundtable meetings and held meetings in all capital cities in the first quarter of 2017, as well as meeting with, and presenting to, advocacy groups such as the Refugee Council of Australia.

The Office also hosts quarterly meetings between our Office, and the heads of the Australian Human Rights Commission, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Australian Red Cross and Foundation House.

Compliance monitoring

The Office conducts an ongoing own motion investigation into the department and the Australian Border Force (ABF) compliance activities that locate, detain and remove unlawful non-citizens. The investigation provides the government and the public with assurance that Australian Border Force's processes are lawful and in accordance with good practice.

We presented at training courses for ABF compliance staff on the functions of the Ombudsman's Office and observed field compliance operations in:

- Darwin – August 2016

- Melbourne – March 2017

- Brisbane – March 2017

- Sydney – April 2017

- Perth – June 2017

- Adelaide – June 2017.

Australian Border Force officers were observed to carry out their duties professionally and we did not identify any areas of significant or systemic concern. However, we identified that many of the administrative issues raised in the field compliance report for 2014–15 report sent to the department in September 2016, remained ongoing areas for improvement in the 2015–16 report, provided to the department in June 2017. Both reports recommended the Australian Border Force:

- ensure that when detaining a person, departmental officers secure and tag the detainee's valuables in bags and provide a receipt to the detainee

- afford detainees a reasonable opportunity to secure and dispose of their assets before their removal, where practicable

- examine options to allow the ABF to seize identity documents such as Medicare cards and passports not belonging to household members.

The 2014–15 report also noted two issues but did not make a recommendation. These related to:

- ensuring officers are aware that when a person requires medication during a field compliance operation, officers must contact the Health Advisory Service for advice

- Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS) displaying some poor practices and difficulties obtaining a TIS interpreter outside of business hours.

The department's response to the 2014–15 report (provided in April 2017) accepted all the report's recommendations and outlined their commitment to address the issues raised in that report.

People detained and later released as 'not-unlawful'

The department provides the Ombudsman with six-monthly reports on people who were detained then later released with the system descriptor 'not-unlawful'. This descriptor is used when a detained person is retrospectively found to be holding a valid visa, usually because of case-law affecting their particular circumstance or because of notification issues surrounding visa cancellation decisions.

For the 2016 calendar year, the department reported that out of a total of 6,876 people detained, 25 (0.36 per cent) were later released as not-unlawful, compared to 22 (0.29 per cent) out of 7,653 persons detained during 2015. The average time people have spent in detention prior to errors being identified, and their subsequent release as 'not-unlawful', decreased from an average of 46 days in 2015 to an average of nine days during 2016.

Generally detention in these cases was not the result of maladministration but a complex immigration record. However, in seven of the 25 cases we noted that the person was the target of an ABF operation. It appears that the ABF systems either do not adequately support field staff who are required to make on the spot decisions, or there is human error involved. Considering the serious consequences of making a wrong decision—that is a person is detained in an immigration detention centre in error—it is important that departmental systems adequately support quality decision making. We regularly see in the reports of people detained and later released as not unlawful that a more thorough examination of departmental records, often by the detention review manager, will identify issues such as invalid notification advices from previous visa decisions. When this occurs it becomes clear that the person still holds a valid visa and that they should be released from detention.

We are aware that two Australians were wrongly held in immigration detention following their release from prison. The department advised the Ombudsman promptly when this was discovered and the department undertook an external review of the situation and provided that report to our Office. The Ombudsman's Office is continuing to engage with the department on these matters.

Immigration Detention Reviews

Statutory reporting (two-year review reports)

When a person has been in immigration detention for two years, and then after every six months, the Secretary of the department must give the Ombudsman a report, under s 486N of the Migration Act 1958, relating to the circumstances of the person's detention.

Section 486O of the Act requires the Ombudsman to give the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection an assessment of the appropriateness of the arrangements for that person's detention. The Office also provides a de-identified version of the assessment that protects the privacy of the detainee and this version is tabled in Parliament and published on the Ombudsman's website.

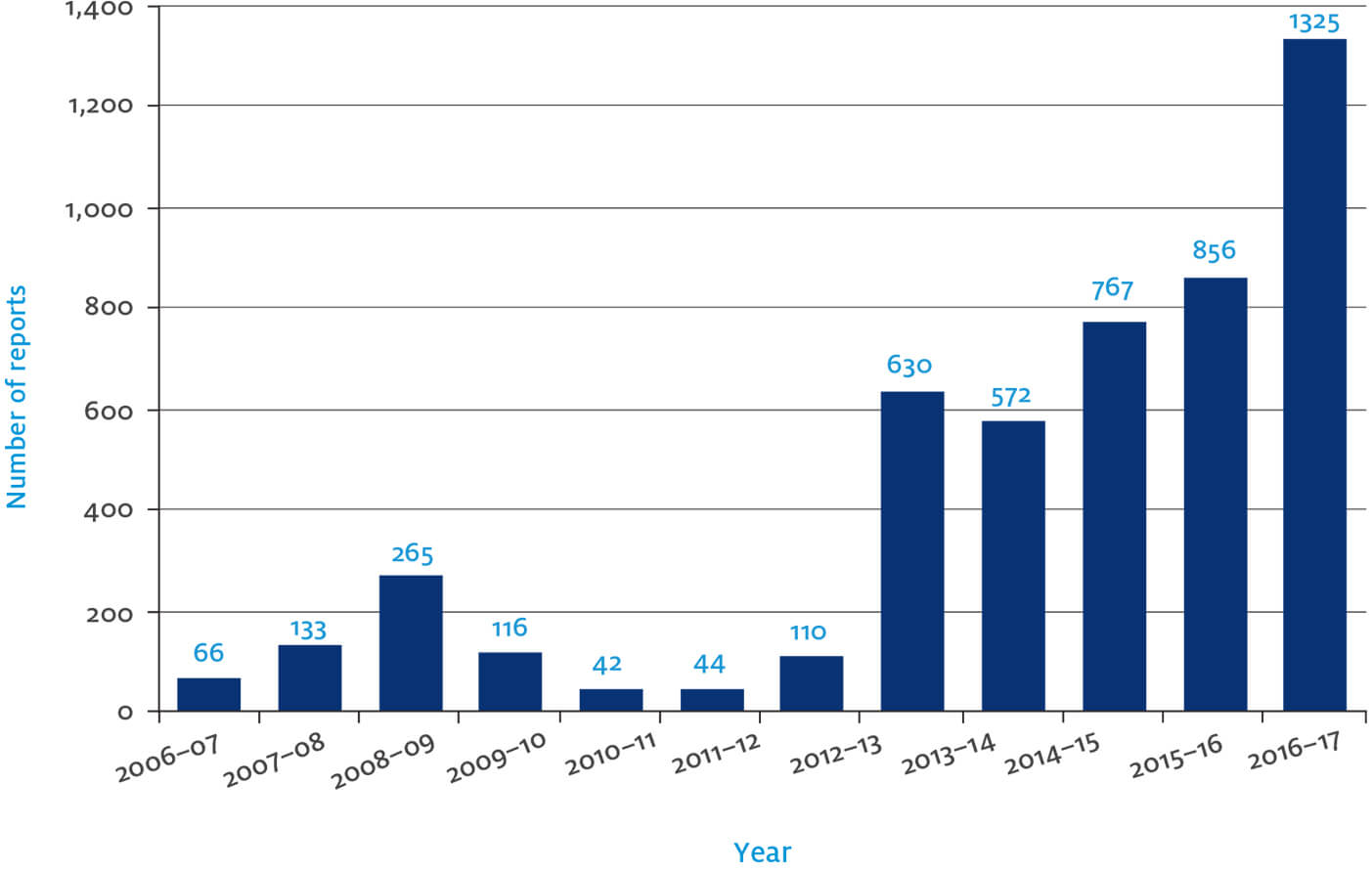

The trend for an increase in the number of assessments the Ombudsman sends to the Minister continued in 2016–17. A total of 1,325 reports were tabled, an increase of 469 (55 per cent) over the previous year.

There was a decrease in the number of s 486N reports received from the department from the previous year's total of 1,662, with 1,320 being received in 2016–17. This trend is forecast to continue and is one factor that is likely to result in a gradual decline in the number of assessments the Ombudsman sends to the Minister in 2017–18.

In 2016-17, we saw an increase in assessments for people who have had their visa cancelled under s 501 of the Act as they did not pass the character test. It is anticipated that this cohort of detainees will continue to increase in 2017–18. However, with the number of detainees being released from detention, either on Bridging or other visas, or being removed from Australia, it is anticipated that this will further reduce the number of assessments the Ombudsman will send to the Minister in 2017–18.

In 2016–17 the Ombudsman made recommendations in 475 assessments. In 296 cases these were generic recommendations that applied to a cohort of detainees, such as those who were barred from lodging visa applications under s 46A of the Act. 169 reports contained recommendations that were specific to the individual detainee, and included matters such as placement within the detention network, access to appropriate medical treatment, having the assessment of their immigration status expedited, and consideration of the granting of a visa or placement into community detention.

Issues raised in the s 486O assessments include:

- delays in the processing of claims for protection

- the possibility of indefinite detention for those assessed as not being owed protection but who are not able to be returned to their home country

- the movement of detainees within the detention network that can impact on their ability to attend specialist medical or court appointments, as well as their access to family support and legal representation

- the uncertainty for people who have returned to Australia from Regional Processing Centres for medical treatment and who, under current policy settings, are not able to have their claims for protection assessed in Australia.

Figure 4 – s 486O assessments tabled by year

Detention inspections

The Office oversights immigration detention facilities and during 2016–17, we inspected the immigration detention facilities listed in Table 7 below:

Table 7 – Immigration detention facility inspections

| Immigration Detention Facility | Location | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Adelaide Immigration Transit Accommodation | Adelaide SA | Oct 2016 Mar 2017 |

| Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation | Brisbane QLD | Nov 2016 Apr 2017 |

| Manus Island Regional Processing Centre | Papua New Guinea | Oct 2016 Feb/Mar 2016 |

| Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre | Melbourne VIC | Nov 2016 Jun 2017 |

| Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation | Melbourne VIC | Nov 2016 Jun 2017 |

| Nauru Regional Processing Centre | Nauru | Aug/Sep 2016 Jun 2017 |

| Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre | Christmas Island WA | Aug 2016 May 2017 |

| Perth Immigration Detention Centre | Perth WA | Aug 2016 May 2017 |

| Perth Immigration Residential Housing | Perth WA | Aug 2016 May 2017 |

| Villawood Immigration Detention Centre | Sydney NSW | Dec 2016 |

| Yongah Hill Immigration DetentionCentre | Northam WA | Sep 2016 Feb 2017 |

The inspection function has been undertaken under the provisions of the Ombudsman's own motion powers9, and in accordance with our jurisdiction to consider the actions of agencies and their contractors. The Office provides feedback to the facility after each visit including any observations and suggestions. The Office submits a formal report to the department at the end of each inspection cycle (every six months). The level of co-operation with this Office across the immigration detention network is generally high, with all staff having a reasonable understanding of the role of the Office.

The key issues that arose over this reporting period include:

- security based models in administrative detention

- restrictive practices within detention

- use of Force and the Continuum of Force

- placement of detainees in the detention network

- management of internal complaints

- introduction of a service provider operational electronic records management system

- programs and activities

- management of detainee property

- access to mobile phones.

Security based model of administrative detention

The Migration Act 1958 enables the detention of unlawful non-citizens, such as those who enter or remain in Australia without a valid visa. Detention has been mandatory for all unauthorised maritime arrivals since 1992 and since 2014, for people whose visas have been cancelled on character grounds. 10

While placement in an immigration detention facility is mandatory for certain cohorts, it is administrative in nature, that is, an individual is detained for the purpose of conducting an administrative function rather than as an end state of the criminal justice system.

The operations of an immigration detention facility is not supported by a legislative framework. The reliance on an administrative rather than a legislative framework to underpin the operations of the immigration detention network remains a key concern for the Office.

During this inspection cycle we noted an increasing emphasis on a security based operational model. While the increasing numbers of detainees with histories of violent or anti-social behaviours require an increased focus on safety and security, we remain concerned that this may be at the expense of a focus on the welfare of detainees. This is not to imply that welfare should be the primary consideration when determining the management program for a detainee, but rather both welfare and security need to be in balance to achieve a fair and reasonable outcome for all concerned.

Security based operational models such as the 'controlled movement model' are the most restrictive of all operational models. Detainees are restricted to accommodation areas and unable to move freely between common areas. Whilst there are circumstances where this model is appropriate, such as in high security compounds, facilities where detainees are vulnerable to coercion or intimidation, or immediately following periods of unrest, this model should not be the first preference for an administrative detention environment.

Restrictive practices in detention

The department and their service providers have a duty of care to both detainees and their staff to protect them from violent/aggressive behaviours and the ongoing risk of damage to people or property. We acknowledge that there are occasions where for the good order, security and welfare of the facility a detainee may need to be placed in restraints or moved to a more restrictive environment. Furthermore, since the implementation of the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection Direction 65, and the subsequent increase of detainees with histories of violent or anti-social behaviours, we have noted an increasing use of these restrictive practices across the immigration detention network.

Without a legislative framework to underpin these practices, the department must rely on its administrative framework to support operating in this environment. We are concerned that the administrative processes underpinning these practices are not as robust as they should be, and have identified shortfalls associated with the:

- use of mechanical restraints when transferring detainees

- use of the controlled movement operational model as the standard operational model

- placement of detainees in behaviour management programs.

Where there is no legislative framework to support the use of restraints or placement in contained environments, the administrative framework must support the principles of procedural fairness, provide independent points of review and appeal, and appropriate mitigation against the risk of such practices becoming punitive in nature.

We acknowledge that the ABF has taken steps to tighten the administrative frameworks surrounding the use of high care accommodation and has adopted practices that provide procedural safeguards for detainees placed in behaviour management regimes. We consider that this area provides a significant area of risk to the department and we would encourage the department to continue to strengthen the administrative framework that supports these critical operational areas.

Use of Force and the Continuum of Force

Over the inspection cycles of this period the Office has noted an increasing use of unplanned force11 by the department when dealing with detainees. While it is accepted that use of force can be necessary to protect the individual, other people or property, we are concerned that the review of incident management records did not reflect the use of de-escalation techniques prior to the application of force.

The continuum of force12 commences with verbal de-escalation and escalates through a number of phases to the ultimate use of deadly force. On occasions, we perceived that some operational staff considered the application of physical force to address noncompliant behaviour as the start-point rather than the mid-point of the continuum. This suggests a continued need for training in this area.

In facilities where additional training in negotiation and de-escalation skills have been undertaken, the Office has observed an overall improvement in the method of engaging with detainees. That is, the first option is to approach a situation with a view to achieving a negotiated outcome first, with the use of force only considered as a last resort.

Placement of detainees within the network

The Commonwealth, through the ABF and its respective facility Superintendents, has a duty of care to all detainees.13 In order to fulfil the duty of care, detainee placements within a facility and the broader network should be made by considering the full set of circumstances of a detainee. The Office remains concerned that placement decisions do not apply adequate weighting to detainee circumstances such as court appearances, specialist medical treatment and family considerations. We acknowledge that the risk assessment of a detainee is a significant consideration, however it would appear that little consideration is given to other factors.

While placement will be driven by operational needs, in particular bed space in east coast facilities, this should not be the sole basis for placing a detainee on Christmas Island or at Yongah Hill. Where the facility is remote and isolated, it is essential that placement decisions take account of all relevant considerations and information.

Of equal concern to the Office is an inaccurate risk assessment or a poorly analysed assessment that is applied without consideration of individual circumstances. Determining that all detainees who have a criminal history involving violence exhibit high-risk behaviour can result in unfair outcomes. Good decision making requires consideration of relevant factors such as the type of behaviour, the age of the detainee at the time of the incident, the passage of time since the incident, and the circumstances that generated the behaviour and the relevance to the current environment. Positive reinforcement of good behaviour is negated in an environment where the negative behaviours of the past consistently dictate the use of restraints or placement in remote facilities.

Towards the end of this reporting period, we have noted an increasing willingness to provide a more thorough analysis to the information upon which the risk assessment is based. The improvement in the provision of information held externally to the department has assisted in this and the ABF continues to work with these sources to maximise the effectiveness and accuracy of the risk assessments.