Part 4 - What we do

HIGHLIGHTS

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Social Services

- Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

- Department of Health

- National Disability Insurance Agency

- Department of Jobs and Small Business

- Indigenous

- Immigration Ombudsman

- Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- Law Enforcement Ombudsman

- Inspections of covert, intrusive or coercive powers

- Defence Force Ombudsman

- Public Interest Disclosure Scheme

- International Program

- Postal Industry Ombudsman

- Overseas Students Ombudsman

- Vocational Education Training Student Loans Ombudsman

- Private Health Insurance Ombudsman

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (DHS) has responsibility for delivering a range of social welfare, health, child support and other payments and services to millions of people across Australia. This includes Centrelink payments and services for retirees, the unemployed, families, carers and students, as well as aged care payments to services that are funded under the Aged Care Act 1997 and child support services.

Our role is to investigate complaints about the administration and delivery of these payments, programs and services. The main DHS programs that the Office receives complaints about includes Centrelink and child support payments and services.

In addition to resolving individual complaints, the Office monitors Centrelink programs to identify systemic issues which raise concerns about administration.

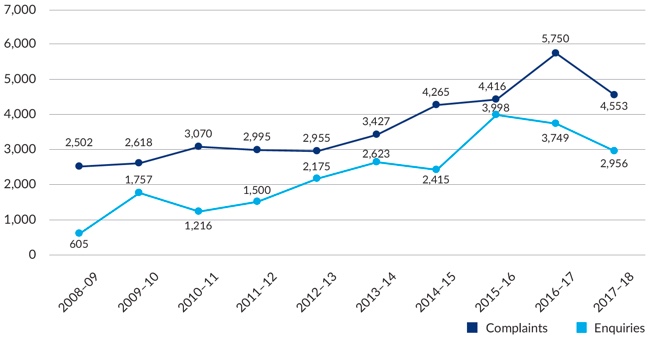

Complaints

In 2017–18, our Office received 12,595 complaints about DHS programs. This represents an 8.9 per cent decrease compared to the 13,832 received in 2016–17. This was largely due to a decline in the number of Centrelink complaints following improvement by DHS in alignment with our recommendations about Centrelink's automated debt system.3

| DHS Programs | 2018–19 |

|---|---|

| Department of Human Services4 | 457 |

| Centrelink | 10,823 |

| Child Support | 1,315 |

| 12,595 |

Centrelink program complaints

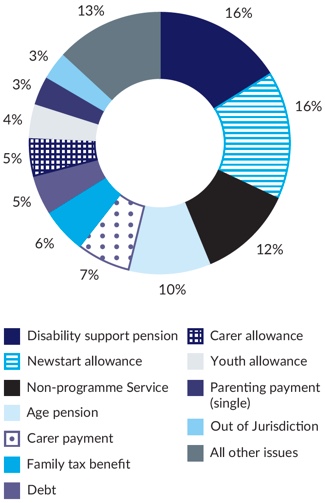

Complaints about Centrelink continue to make up a substantial proportion of the overall complaints made to the Office, representing 28 per cent of the total number of in-jurisdiction complaints. Approximately 32 per cent of issues raised in Centrelink complaints are about disability support pension (DSP) and newstart allowance (NSA). Figure 3 illustrates the main Centrelink issues.

Figure 3 – Complaint issues

Submissions

The Office made submissions to Parliamentary Inquiries into amending legislation and other matters relevant to payments and programs administered by DHS, including with regard to the:

- Social Services Legislation Amendment (Welfare Reform) Bill 2017

- the Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee Inquiry into the Digital Delivery of Government Services.

Monitoring of systemic issues

The Office continued to monitor a number of systemic issues during 2017–18. As in our 2016–17 Annual Report, the most significant of these continued to be DSP claims processes, Centrelink internal review processes and the data-matching employment income compliance reviews.

In 2017–18, improvements were made in all three areas:

- DHS instituted a new streamlined process for DSP claims, incorporating our feedback and lessons from our report Accessibility to the DSP for Remote Indigenous Australians.

- DHS conducted a review of its internal review process. DHS proposed a new internal review model which addresses concerns raised in earlier reports by our Office and incorporates additional feedback provided by the Office during the review process. We will monitor the new claims and internal review processes throughout 2018–19.

- Debt-data matching complaints have fallen from a peak of 651 in the first quarter of 2017 (January–March), which was prior to the publication of our report into Centrelink's automated debt raising in April 2017, to 208 in the most recent quarter (April–June 2018).

In January 2017, debt-data matching complaints represented 17.5 per cent of Centrelink complaints to the Office. This reduced to 3.5 per cent of Centrelink complaints to the Office in early 2018. In April to June 2018 we received an increase in debt-data matching complaints that corresponded to an increase in DHS debt data matching activity.

Own motion investigations and issues monitoring

In 2017–18, the Office monitored the ongoing administration of the automated debt program and the ongoing implementation of recommendations made in our April 2017 report.

In 2018–19, we will continue to closely monitor the program and offer assistance to further improve administration. In addition to operational level meetings, briefings and system demonstrations that occur on regular and ad hoc bases, senior staff from our Office and DHS continue to meet regularly to monitor and progress administrative improvements.

Child Support program

Our Office has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about DHS' administration of Child Support program functions. This includes child support assessments, registering child support agreements, and collecting and disbursing child support between separated parents and the carers of eligible children.

The number of complaints received about Child Support remained relatively stable in 2017–18, with a 3.5 per cent decrease in complaints. The majority of complaints received in 2017–18 were from paying parents. The main complaint themes were regarding the collection and enforcement of child support liabilities, formula assessments, change of assessments and customer service.

In addition to investigating individual complaints, the Office liaised with DHS on Child Support matters, including the rollout of the new child support Information Technology system and changes to lodging online complaints. We also sought and received briefings on, and monitored the passage of, legislative changes affecting child support assessments. We will continue to closely monitor complaints for issues that may arise when DHS implements these changes.

CASE STUDY

Greg made a complaint to our Office, advising that DHS used a higher income than he actually earned to assess his child support liability. He told us he could not afford the payments DHS was deducting from his wages to repay the child support arrears he owed. Greg advised DHS he was in financial hardship and was concerned he could become homeless.

After we investigated Greg's complaint, DHS advised our Office that in June 2017 Greg's child support liability had increased when the receiving parent applied for a change of assessment in special circumstances. DHS is obliged to give Greg an opportunity to respond to the information provided by the other party, however DHS told us that Greg's response was not considered when deciding to increase the liability. Greg's objection in September 2017 was also not considered as it had not been lodged within the required timeframe and an extension of time had not been sought.

Following our investigation, DHS provided Greg an extension of time to object to the change of assessment decision. DHS reviewed the change of assessment decision and reduced Greg's annual child support liability by approximately $4,000.

To address Greg's financial hardship concerns, DHS significantly reduced his weekly arrears repayment and apologised to Greg for the way his case was handled. DHS also provided feedback to staff on the importance of considering all information when making decisions.

Department of Social Services

Engagement and monitoring of systemic issues

Throughout the year we engaged with the Department of Social Services (DSS) on a number of systemic issues, including the administration of the National Rental Affordability Scheme, accessibility of DSP, effectiveness of legislated garnishee safeguards and use of Indigenous language interpreters.

We also provided input on the establishment of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) Quality and Safeguards Commission, and the National Redress Scheme for Institutional Child Sexual Abuse.

Legislated garnishee safeguards

DSS has policy responsibility for the Social Security (Administration) Act 1999, which has safeguards to ensure that certain deposits held by financial institutions are quarantined in the administration of garnishee and garnishee-like orders. However, these safeguards were drafted before technological advances in the banking sector and are less effective in the context of modern banking practices.

In 2017–18, the Office led liaison with DSS to identify solutions to problems with the effectiveness of legislated garnishee safeguards identified in our joint work with the New South Wales (NSW) Ombudsman. DSS acknowledged the issues raised by our Office and is now considering options to address these concerns. We will continue to liaise with DSS on these issues in 2018–19.

The Office will also continue to engage and collaborate across jurisdictions to improve the administration of garnishee orders for vulnerable people and build on previous work done with the NSW Ombudsman. This project will develop and consider options for administrative reform that aim to reduce the risk of financial hardship for social security payment recipients subject to garnishee arrangements.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet

Indigenous language interpreters

In 2016–17 we investigated what steps had been taken to implement recommendations in our December 2016 report on the accessibility and use of Indigenous language interpreters. While there is still work to be done to improve accessibility, there has been progress since the publication of our report, especially among agencies participating in the reconvened Interdepartmental Committee for Indigenous Interpreters.

In December 2017, PMC published a new Protocol on Indigenous Language Interpreting for Commonwealth Government Agencies incorporating all 17 best practice principles proposed in our report.

Community Development Programme

Our Office continued to monitor administration of penalties applied to remote job seekers in the Community Development Programme (CDP).

The programme has also been reviewed by the Australian National Audit Office5 and a Senate Committee Inquiry.6

Our investigations concentrated on administrative issues not already canvassed by other oversight bodies, with a particular focus on the point where administration by the CDP providers and the DHS intersect.

In the complaints we investigated, a number of issues arose including problems with:

- processes for identifying and recording relevant information (including information about vulnerability, interventions to address job seeker barriers, details about job seekers contact attempts and reasons/excuses provided)

- the flow of information between providers and DHS

- barriers to accessing employment services assessment processes

- wait times on the DHS Participation Solutions Team (PST) telephone line

- accessibility and use of interpreters.

We also found some examples where administrative processes were failing to identify and adequately address vulnerability and work capacity issues.

The investigation also informed our response to PMC's consultation paper Remote Employment and Participation.

CASE STUDY

John's vulnerability indicator for cognitive impairment had expired in 2013. Despite the information on his file, he was not assessed by DHS as having a partial capacity for work and, instead, was required to participate in full-time Work for the Dole activities in order to receive income support. He was referred for an employment services assessment on numerous occasions, but these were unable to take place as he did not provide the required medical evidence to support the employment services assessment process.

As a result of not meeting these activities, John's lawyer advised us he had incurred numerous penalties and struggled to have his payments restored. John spent nearly five months without income support. He was not offered an interpreter and had difficulty accessing the DHS PST telephone line.

During our investigation we found John's Centrelink record showed significant barriers to work, including language barriers, cognitive impairment, dementia-like symptoms, social withdrawal, disorganised thought patterns, reduced concentration and memory, very low literacy and numeracy and reliance on his partner to speak for him and tell him what to do.

Following our investigation, John was granted the disability support pension, and our Office provided comments and suggestions to both PMC and DHS.

Both agencies responded positively to our comments resulting in numerous administrative changes. Highlights include:

- PMC is revising its guidelines to improve identification and recording of relevant information. It has increased the weighting of performance targets for supporting job seekers to overcome barriers and proposes to reduce relevant medical evidence thresholds.

- DHS will stop its practice of 'auto ending' vulnerability indicators such as cognitive impairment indicators where review timeframes expire. It is employing new strategies to address PST wait times and is reviewing its guidelines and training for staff.

Department of Health

The Department of Health (Health) has responsibility for programs and policies delivering health, aged care and sports outcomes.

Complaints

In 2017–18, our Office received 164 complaints about Health. This represents a 198 per cent increase compared to the 55 received in 2016–17. The majority of these complaints were about the My Aged Care program (in particular the Home Care Packages Program) which represented 44 per cent of the total complaints received about Health. We also received complaints about the Aged Care Assessment process and Aged and Community Care which represented 15 per cent of the total complaints received about Health.

The increase in complaints about My Aged Care was attributable to government reforms which took place in February 2017. These reforms were designed to make home care packages more accessible and flexible for consumers.

As a result of the reforms, Health now has the responsibility for assigning a client a home care package in line with the Aged Care Act 1997. The responsibility for paying the government subsidy to the aged care provider, in line with the Aged Care Act 1997, still remains with DHS.

The majority of complaints we received related to two issues:

- home care packages being withdrawn in error

- delays in assigning a home care package.

There were also complaints to our Office about the way My Aged Care complaints were handled by Health.

In response to the increase in complaints, the Office has been working closely with Health and providing feedback on its complaint-handling process and the information it makes available to providers and consumers.

In December 2017, Health agreed to a transfer protocol with our Office where we transfer My Aged Care complaints directly to Health to resolve directly with the complainant (see example in the case study below). We have also made a number of comments and suggestions to Health about the administration of the My Aged Care program.

CASE STUDY

Beatrice and Andrew complained to our Office about issues they were experiencing with their parents' home care packages. They advised us they had contacted Health on multiple occasions but the issues had not been fixed. In each case, My Aged Care referred the complainants to DHS to fix the issue. When the complainants approached DHS, they were advised to go back to Health.

Our Office asked Health and DHS for information about their respective responsibilities and ultimately the matters were resolved. However, we were concerned that these complaints demonstrated there was a lack of communication between both departments. In finalising these two complaints, our Office suggested to Health and DHS they consider implementing a 'no wrong door' approach where each department can transfer complaints to the other in relation to My Aged Care matters.

Both departments accepted our suggestion and have created a checklist and a process map to assist staff to ensure all actions are explored before transferring a person to the other department. They are also implementing a warm transfer process between both departments.

National Disability Insurance Agency

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) administers the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a Commonwealth scheme that provides funding to people with a permanent and significant disability to assist them to participate in everyday activities. People who enter the NDIS are known as participants.

The NDIS is being introduced gradually across Australia. There were over 180,000 participants in the NDIS at 30 June 2018 and there will be around 460,000 by the time the national rollout is complete in July 2020. How and when people with a disability are able to access the NDIS depends on the state or territory they live in and whether they have accessed disability services previously.

Our Office handles complaints about the NDIA's administrative actions and decisions. We can also consider complaints about organisations who are contracted to deliver services on behalf of the NDIA, including local area coordinators who conduct information-gathering and pre-planning interviews, and Early Childhood Early Intervention partners.

Complaints

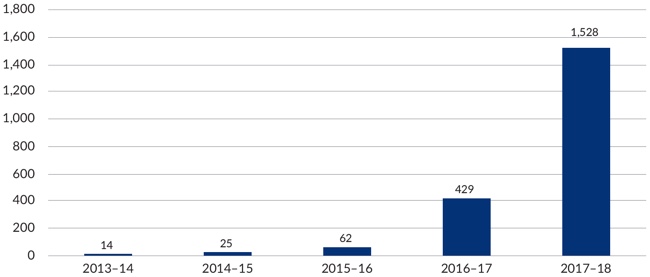

In 2017–18 we received 1,528 complaints about the NDIA, which is a 256 per cent increase on the 429 complaints received in 2016–17. During the same period the number of NDIS participants almost doubled.

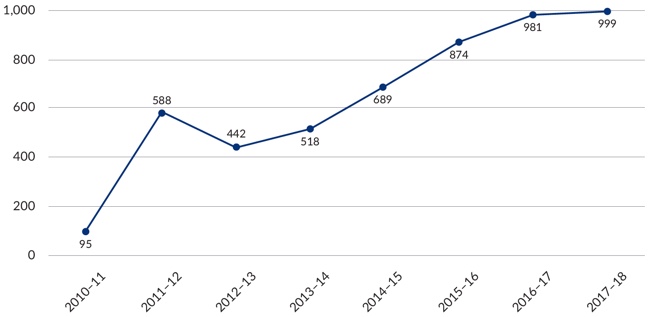

Figure 4 – NDIA complaints received

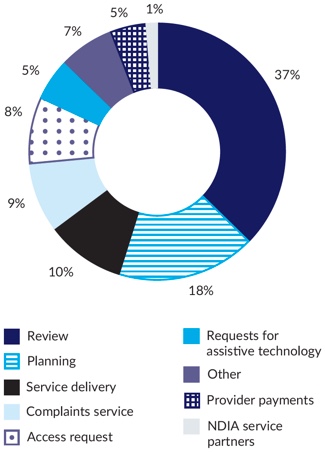

Complaints to our Office in 2017–18 covered many aspects of participants' experiences with the NDIS as well as, to a lesser extent, providers' experiences. The most common complaint issue was the NDIA's handling of reviews of plans and decisions.

Other common complaint issues included:

- difficulty and delays in having quotes approved for assistive technology, including home and vehicle modifications

- dissatisfaction with the process and outcome of planning meetings

- providers having difficulty making service bookings and receiving payment

- inconsistencies between undertakings provided in planning meetings and the types and amounts of supports included in the final NDIS plan

- delays in receiving plans following planning meetings

- confusion about timeframes for receiving an NDIS plan after access to the scheme is granted.

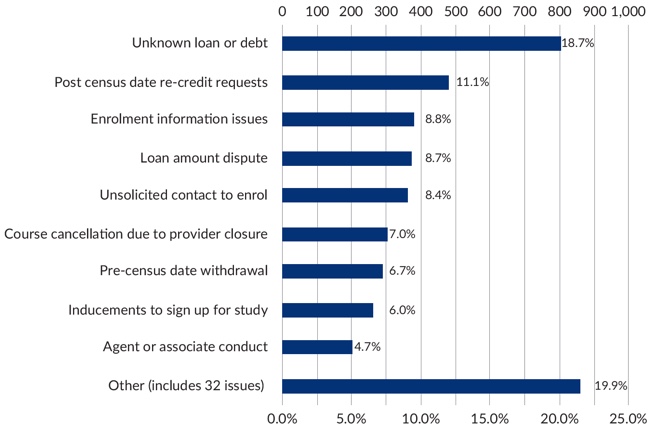

A breakdown of the most common complaint issues7 is provided in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5 – NDIA complaint issues 2017–18

Handling of reviews

In our 2016–17 Annual Report we noted the NDIA's handling of reviews featured prominently in complaints to our Office and suggested the review process was likely to be a focus for us going forward. In 2017–18 just over a third of all NDIA related complaints to our Office were about the NDIA's review process.

In May 2018 the Ombudsman issued a public report8 highlighting a number of issues with the NDIA's approach to handling reviews. More information about the report is included under Reports later in this section.

Accessing assistive technology

Many complaints about the NDIA in 2017–18 highlighted difficulties participants experienced including funding for assistive technology9 in their NDIS plan. The most common complaints about accessing assistive technology included:

- delays in making decisions

- lack of clear guidance about how to make a request and what information or evidence is required

- inconsistencies in advice about who can prepare assistive technology quotes and what they need to include

- confusion about how and where assistive technology funds can be spent.

In May 2018 the NDIA implemented a new approach to managing requests for assistive technology items, which it considers will simplify and expedite its handling of straightforward requests. We will be monitoring this approach during 2018–19 to identify whether these changes resolve the issues highlighted in complaints to our Office.

CASE STUDY

Andrea, a disability advocate, complained to us about the NDIA's handling of her client Anna's request for home modifications. Andrea explained the NDIA had failed to provide clear information about who is able to provide home modification quotes and what information they must include in their quotes. She complained that, as a result, a decision on Anna's request for home modifications was unreasonably delayed.

Andrea told us Anna's occupational therapist (OT) sent the NDIA a quote for home modifications along with an occupational therapy assessment report, but the NDIA refused to consider the quote because Anna's OT had not completed NDIA training to be able to complete quotes. The NDIA provided Andrea with a list of suitable OTs so a new quote could be obtained.

Andrea then assisted Anna to obtain a quote from an NDIA-trained OT. When Andrea provided the new quote to the NDIA, she was told she needed at least two quotes. However, a month after submitting the second quote, NDIA staff told Andrea they could not accept either quote as they were not itemised.

In response to feedback provided as a result of our investigation, the NDIA undertook improvements to its training material and internal guidance documents for staff. The NDIA also improved its external communications material–for providers and participants–to make the requirements for home modification requests clearer.

Planning process and outcomes

Dissatisfaction with the NDIA's planning process continued to be a theme for complaints this year. Many participants and family members told us they were confused about how and when planning meetings should take place and, in some instances, they felt this prevented them from providing sufficient detail or evidence about the types and amount of support requested.

In other cases, complainants said the goals and supports discussed at the planning meeting were left out of the final plan and it was not always clear whether this was an oversight or the planner had decided these supports should not be funded.

In late 2017 the NDIA commenced a trial of a new approach to planning which sees the participant, local area coordinator and planner meet to jointly develop a plan. Wherever possible, the participant will receive a copy of the plan at the meeting and have the opportunity to discuss any concerns or questions before the plan is finalised.

We consider this is a significant improvement on the current approach, where participants may receive their plan days or weeks after the planning meeting and must lodge a request for internal review if they disagree with the type or amount of supports included. We will monitor the progress of the new planning approach in 2018–19. We will also monitor the development and implementation of the NDIA's approaches tailored specifically for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants, culturally and linguistically diverse participants and participants with psychosocial disabilities.

CASE STUDY

Lawrence complained to us, on behalf of Christina, about the NDIA's approach to planning for Christina's daughter, Alice. In particular, Lawrence said he thought the NDIA had acted unreasonably by conducting a planning meeting to finalise Alice's plan even though her mother, Christina, had indicated she was obtaining additional evidence relevant to Alice's support needs.

Lawrence told us the NDIA notified Christina it had scheduled a planning meeting for Alice. Christina asked that the meeting be delayed to allow her to obtain a medical report she considered would more clearly demonstrate the support Alice needed. Despite this request the NDIA proceeded with the planning meeting, telling Christina she could request a review of the plan when she obtained the additional report.

Our investigation of Lawrence's complaint identified the NDIA had processes in place to pause or delay planning in the event of 'personal circumstances'. We concluded, based on Christina's experience, that the NDIA could improve how it communicates this option to staff.

We suggested the NDIA revise its guidance material to widen the range of circumstances in which staff can suspend or delay planning to include situations where a participant requires additional time to prepare or source supporting information.

The NDIA agreed with our suggestion and also apologised to Christina for proceeding with Alice's planning meeting before Christina had a chance to provide additional information.

Stakeholder engagement

Presentations

In 2017–18 staff members presented to:

- Advocacy organisations funded to assist NDIS participants with internal and external review processes, at forums convened by the Department of Social Services in Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane.

- The NDIA's regional complaints officers' forum in January 2018.

These presentations gave us the opportunity to raise awareness of our role in the NDIS Quality and Safeguarding Framework and to share best practice approaches to making and handling complaints.

Western Sydney community round table

In December 2017 staff convened a community round table event in Western Sydney, where we invited local community and government stakeholders to:

- learn more about the role of the Office

- talk to us about issues they or their clients experience in dealing with Australian Government agencies, including the NDIA.

We received positive feedback following the event and hope to run similar events in other parts of Australia in 2018–19.

Submissions

In August 2017 we made a submission to the Joint Standing Committee on the NDIS' inquiry into the Provision of services under the NDIA Early Childhood Early Intervention (ECEI) Approach. Our submission highlighted issues raised in complaints and stakeholder feedback, including:

- delays in developing plans after access was granted

- a lack of suitable providers in certain areas which, in turn, causes significant delays in accessing services

- concerns about whether the NDIA's approach to the types and amounts of funded supports is consistent with best practice for early intervention services.

The Joint Standing Committee released its inquiry report in December 2017, making 20 recommendations aimed at improving the effectiveness of the NDIA's ECEI approach. We will continue to work with the NDIA during 2018–19 to monitor its implementation of the recommendations.

Reports

The NDIA's handling of reviews

In May 2018 the Ombudsman issued a public report10 highlighting a number of issues with the NDIA's approach to handling reviews.

These included:

- Poor communication–for example, review requests not being acknowledged, requests for updates not being responded to and participants being provided with incorrect information about their review rights.

- Delays–in particular, participants waiting up to nine months for a decision on their review request due to significant backlogs and the absence of timeliness standards for completing reviews.

- Gaps in staff training and guidance–for example, the absence of clear directions to staff about acknowledging reviews within standard timeframes and ensuring template letters require review officers to provide reasons for their decision.

The report made 20 recommendations for improvement, all of which were accepted by the NDIA. The NDIA's response to the report also advised it had commenced action to implement some of the recommendations. We will monitor the NDIA's progress against the recommendations during 2018–19.

Changes to the quality and safeguarding arrangements for the NDIS

Collaboration with oversight bodies

In July 2018 the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (the NDIS Commission) will commence operation in New South Wales and South Australia. In these states, the NDIS Commission has oversight of NDIS providers and is responsible for:

- registration and regulation of NDIS providers

- compliance monitoring, investigation and enforcement action

- responding to concerns, complaints and reportable incidents

- oversight of behaviour support, including monitoring the use of restrictive practices, with the aim of reducing and eliminating those practices

- leading collaboration on the design and implementation of nationally consistent NDIS worker screening

- facilitating information-sharing arrangements with the NDIA, state and territory and other Commonwealth regulatory bodies.

Prior to the commencement of the NDIS Commission, most of these functions were administered by oversight bodies at the state level. Transferring these functions to the NDIS Commission in New South Wales and South Australia is the first step to implementing a national approach to quality and safeguarding arrangements for the NDIS. The NDIS Commission will start operating in all other states and territories (except Western Australia) from 1 July 2019, and in Western Australia from 1 July 2020.

During the transition from state and territory arrangements to the NDIS Commission, we anticipate NDIS participants and providers may need additional help to understand the options for making complaints about the NDIA and NDIS service providers. We will aim to work closely with the NDIS Commission and the remaining state and territory oversight bodies during 2018–19 to:

- promote the right to make complaints and provide information about how to access complaint systems

- reinforce a 'no wrong door' approach to complaints, where oversight bodies assist complainants to make contact with the body that is best placed to handle their complaint.

Complaints about the NDIS Commission

Like all Australian Government agencies, the NDIS Commission is expected to have a robust and accessible process for handling complaints about its services. If the affected person or organisation is not happy with the way the NDIS Commission handles their complaint, they can make a complaint to our Office.

If we decide to investigate a complaint, we may consider the NDIS Commission's handling of the complaint and the administrative actions or decisions about which the person complained.

Department of Jobs and Small Business

The Department of Jobs and Small Business is responsible for national policies and programs that help Australians to find and keep employment and to work in safe, fair and productive workplaces.

Complaints

In 2017–18, the Office received 292 complaints about the Department of Jobs and Small Business (DJSB) programs. This represents a 23 per cent decrease compared to the 382 received in 2016–17. The majority of the DJSB complaints related to the jobactive program, which represented 80 per cent of total complaints. Of the complaints about jobactive, 16 per cent of complaints were about the standard of service. Out of the 292 complaints received, the Office investigated 48.

Jobactive program participants are, in the first instance, encouraged to make a complaint to their provider. Where they are dissatisfied with the outcome of their complaint to the provider, or they have other reasons for not wishing to make the complaint directly to their provider, jobactive participants are able to access the DJSB National Customer Service Line either by phone or email. The DJSB has also a complaint form available on its website.

Stakeholder engagement

Through our investigations, the Office has provided feedback and guidance to the DJSB on complaint-handling practices and policies, improvements to the practices of the National Customer Service Line and suggested process reviews.

The Office has also been sharing the lessons learned from DHS' automated debt system with the DJSB to inform the development of the Targeted Compliance Framework and supporting online systems for use by job seekers and employment services providers. We note that, consistent with the strategies developed by DHS, the DJSB has taken a user-centred design approach to the new system. This system aims to make the reporting and monitoring of job seeker activities as easy as possible.

We will continue to monitor the implementation of the new compliance arrangements throughout 2018–19 and will raise any concerns and issues that arise from complaints received from people subject to the framework.

Indigenous Australians

Reconciliation Action Plan 2018

On 13 February 2018 the Office launched its 2018 Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP). The launch coincided with the 10th anniversary of the National Apology to the Stolen Generations.

Our RAP provides a public commitment to continuing reconciliation. It includes practical steps to build relationships with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, and to increase our understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and histories. The RAP is part of our work to make our services more accessible to Indigenous peoples.

Implementing the Indigenous Accessibility Review recommendations

In our 2016–17 Annual Report we reported that Aboriginal communications company Gilimbaa Pty Ltd had completed a review of the Office's accessibility and inclusiveness of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities. The review considered all aspects of the Office's operations and made recommendations to improve our approach to engaging with Indigenous complainants and stakeholders.

During 2017–18 we focused on implementing recommendations from the review to improve our external communication practices. At the launch of our RAP we released a new range of Indigenous communication products including posters and brochures centred on the key message 'Your Story Matters'. We anticipate running a national campaign using these products in 2018–19.

Launch of 2018 Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP). L to R: Jaala Hinchcliffe Deputy Ombudsman, Russell Taylor AM, Michael Manthorpe PSM Commonwealth Ombudsman, Charles Turner Indigenous Manager, Fiona Sawyers Senior Assistant Ombudsman Strategy

APY Outreach

Stakeholder engagement

Engaging with Indigenous communities and organisations

We use a range of media including social media, radio interviews, outreach to rural and remote areas and roundtable discussions to increase awareness of our services, explain the complaint-handling process and highlight the value of complaints to achieve individual and systemic outcomes.

In 2017–18, we:

- Participated in radio interviews with the Anangu Lands Paper Tracker project11 and the Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Service.12

- Visited Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory and the Anangu Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands in remote South Australia.

- Hosted roundtable discussions in Western Sydney.

- Participated in outreach and complaints clinics in Bunbury and Busselton in Western Australia as part of the Western Australian Ombudsman's Regional Access and Awareness Program.

Engaging with peer organisations involved in complaint-handling

Australia New Zealand Ombudsman Association–Indigenous Engagement Interest Group

Our Office facilitates the Australian and New Zealand Ombudsman Association (ANZOA) Indigenous Engagement Interest Group, which provides opportunities to share information, resources and experiences with a view to improving complaint-handling practices and procedures for Indigenous peoples. The group meets quarterly and includes participants from parliamentary and industry ombudsmen offices from Australia and New Zealand.

Dr Jackie Huggins AM FAFH addressing staff from Brisbane Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman during National Reconciliation Week 2018

Indigenous Right to Complain Working Group

Our Office provides leadership and support for an Indigenous Right to Complain Working Group. This group includes members from a range of government and non-government organisations at the state, territory and national level.

The working group provides a forum for sharing information, ideas, strategies, contacts and coordinating joint outreach aimed at increasing awareness of complaint rights and options for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities.

Both of these groups contribute to building a 'no wrong door' approach to Indigenous complaint-handling across agencies, oversight bodies and community stakeholders. They provide opportunities for agencies to reflect on the effectiveness of their strategies for promoting the right to complain and ensuring complaint-handling systems are accessible and inclusive for our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Special events–marking National Reconciliation Week 2018

On 29 May 2018, to acknowledge National Reconciliation Week, the Co-Chair of the National Congress of Australia's First Peoples, Dr Jackie Huggins AM FAFH, attended our Brisbane office to provide an all-staff address. Throughout her address she encouraged staff to learn more about our shared histories and consider how we can individually and collectively contribute to achieving reconciliation.

Issues monitoring

We continue to monitor a number of significant issues of interest related to the delivery of Australian Government services to or for Indigenous peoples. This year, the most significant issues were:

- Centrelink debts

- Community Development Program participation penalties and compliance assessments.

Immigration Ombudsman

The Office investigates complaints about the migration and border protection functions of the Department of Home Affairs (the department) and its operational arm, the Australian Border Force (ABF).

The Office, through the Ombudsman's own motion powers, also:

- monitors the ABF's compliance activities involved in locating, detaining and removing unlawful non-citizens

- undertakes inspections of immigration detention facilities in Australia and elements of offshore processing centres that are within our jurisdiction.

Under the Migration Act 1958 (Migration Act), the Office also has a statutory role to provide the Minister for Home Affairs an assessment of the appropriateness of a person's detention when that person has been in immigration detention for two years and for every six months thereafter.

Complaints

In 2017–18 we received 1,838 complaints about the department, compared with 2,071 complaints in 2016–17, a decrease of 11.3 per cent. Of these, we investigated 322 (17.1 per cent).

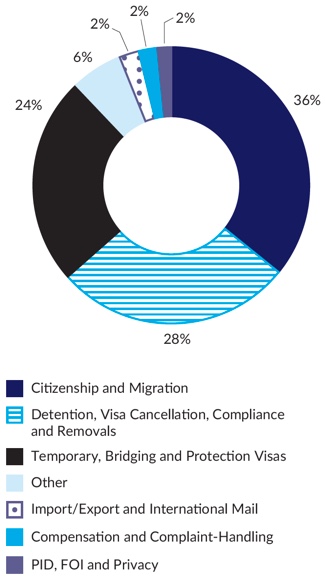

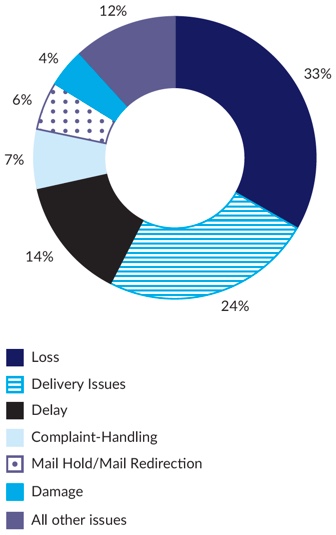

Complaints concerning Citizenship and Migration made up the largest category of the complaints received by the Office followed by complaints about immigration detention. Immigration detention complaints reflected similar themes to those in previous years: loss or damage to detainees' property, placement within the detention network and medical issues such as access to specialist care, appropriate treatment for injuries and illness and delays in the processing of claims for asylum.

In 2017–18 we closed 2,116 complaints compared to 2,382 in 2016–17. In 2017–18 we investigated 322 complaints and achieved 445 remedies for complainants.

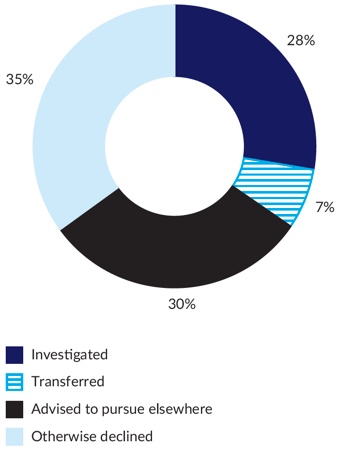

Figure 6 – Breakdown of immigration complaints closed in 2017–18

CASE STUDY

In 2015, the department refused Marina's application for an offshore partner visa because it was not satisfied the couple were in a genuine and continuing relationship.

Marina's partner, Ehsan, sought review of the decision by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT), which remitted the application back to the department for reconsideration with the direction the couple were in a genuine and continuing relationship.

Approximately 10 months after the AAT's decision, the department granted Marina a temporary partner visa. However, the next day, the department notified Marina that her application for a permanent partner visa had been refused as the delegate was again not satisfied of their genuine and continuing relationship.

As Marina had not been able to travel to Australia during the 24 hours her temporary visa was in effect, the AAT could not review the decision. This is because the AAT is only able to review a decision to refuse a permanent partner visa if the applicant is in Australia when they apply for review.

Ehsan complained to our Office because he could not understand how he and Marina could be considered to be in a genuine relationship on one day and then to not be in a genuine relationship the following day.

During our investigation, the department acknowledged the decision to refuse Marina's permanent visa was not a lawful one, and the decision was set aside.

In November 2016, the department told Marina that her temporary visa would be in effect until a fresh decision was made. However, her application for the permanent visa was again refused the following day on the basis that the department remained unsatisfied that the relationship was genuine based on the evidence before the case officer.

The reasons provided included that the delegate would expect to see evidence of the couple making 'firm arrangements' for Marina's arrival in Australia and evidence the couple was taking steps to build a life together. Significant weight was placed on the fact the couple had not provided further evidence supporting their ongoing relationship post the AAT decision in 2015.

During our investigation, we considered that in refusing the application, the delegate relied on outdated and irrelevant information. The couple were not in a position to know when a decision would be made and were not able to make 'firm arrangements' for Marina's arrival in Australia. Also, the couple had not been provided with an opportunity to provide evidence in support of their ongoing relationship prior to the permanent application being refused. We were also concerned the permanent application was again refused within one day of the temporary partner visa being re-enlivened.

In late 2017, the department acknowledged this refusal decision was not lawful and would be vacated. This meant that Marina's temporary visa would be in effect until a fresh decision was made. By now, considerable time had passed since Marina's temporary visa was first granted in 2016.

That visa had an 'entry before date' which required Marina to enter Australia before a specified date, which could not be changed. When Marina's temporary visa was re-enlivened, it was only valid for one more day. However Marina traveled to Australia while her temporary visa was still valid to await the processing of her permanent partner visa application.

Complaints can contain multiple issues, therefore the number of remedies can be greater than the number of complaints investigated.

| Remedy | 2017–18 |

|---|---|

| Explanation | 312 |

| Action expedited | 42 |

| Decision changed or reconsidered | 37 |

| Other non-financial remedy | 16 |

| Remedy provided by agency without Ombudsman's intervention | 11 |

| Law, policy or practice changed | 10 |

| Apology | 1 |

| Financial remedy | 9 |

| Agency officer counselled or disciplined | 7 |

Stakeholder engagement

The Office continues to engage regularly with officers from the department and the ABF. We have also received briefings on policy changes and issues of interest.

We publish an e-newsletter, Immigration Matters, to share information about our priorities and issues of interest with external stakeholders.

We also host quarterly meetings with the Australian Human Rights Commission, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the Australian Red Cross and Foundation House.

In 2017–18 we presented to the department on the role of our Office. Office representatives also presented at the ABF's training courses for Compliance and Removal Superintendents and s 251 warrant holders on our compliance monitoring and other immigration activities.

Own motion investigations

During 2017–18, our Office released three own motion investigation reports:

Investigation report on delays in the clearance of International Sea Cargo13

The investigation was prompted by complaints about delays in the processing of containerised sea cargo by the department and the ABF resulting in substantial additional costs for importers. After initial engagement with the ABF, the scope of the investigation was broadened to include biosecurity interventions at the border due to the Department of Agriculture and Water Resource's (DAWR) power to place a border hold on containers independently of the ABF.

Our investigation focused on the efficiency of the administrative systems and the procedures that support the exercise of the ABF and DAWR's powers to hold and inspect cargo.

We identified that while the ABF has well-established administrative processes to manage containerised sea cargo compliance, more could be done to manage backlogs at cargo and container examination facilities (CEFs). This, in turn, could minimise delays and reduce the costs imposed upon industry.

The report concluded that the major reason for these delays was the reduced operational capacity at CEFs during peak times. The requirement for simultaneous inspections and physical examinations at times when staff are unavailable due to surge redeployment was also identified as a significant cause of pre-inspection delays.

The report made 10 recommendations–eight related to the department and the ABF, one to DAWR and one recommendation applying to both agencies. The department accepted six of these in full and three in part. DAWR partially accepted the two recommendations that applied to it.

Investigation into the circumstances of the detention of Mr G, maintaining a reasonable suspicion that a person is an unlawful non-citizen14

In August 2017, the Office investigated the detention of Mr G, who spent nearly four years in immigration detention before being removed to his country of origin. Mr G was originally detained in October 2013 when his partner visa application was refused and his associated bridging visa was ceased. The department later found that an error in the notification of the partner visa refusal meant that the notification was defective and his bridging visa was still valid.

In response to the Office's investigation, the department advised that an error in the partner visa refusal notification process was not known at the time of Mr G's initial detention. This error came to the department's attention five months after his detention in March 2014.

While the department undertook a review of cases that may have been affected by the error in the notification process, Mr G's case was not identified in that process. Subsequent monthly reviews of his case also failed to identify the issue with the visa refusal notification.

In our report, we expressed concern regarding the department's review processes for maintaining a reasonable suspicion that an individual continues to be an unlawful non-citizen and as a result should continue to be held in immigration detention.

The department accepted all four of the Ombudsman's recommendations, noting that the implementation of three of them depended on the outcome of ongoing litigation relating to other individuals that raised similar concerns.

Delays in processing of applications for Australian citizenship by conferral15

In July 2016, the Office commenced an own motion investigation into the then Department of Immigration and Border Protection's (DIBP) processing of applications for Australian citizenship by conferral that require enhanced identity and integrity checks. This was in response to increasing complaints to our Office from people who were subject to enhanced integrity and identity checks that resulted in extended processing times for their citizenship applications.

In 2016–17 DIBP received 201,250 applications for citizenship by conferral. Given some people had applications pending for over 18 months, without having been referred for identity and integrity checks, we considered that a systemic investigation into these issues was more appropriate than commencing a series of individual complaint investigations.

The report made four recommendations to DIBP aimed at improving the quality of information in the Australian Citizenship Instructions (ACI) in order to achieve greater certainty and timeliness in complex identity and character assessments. DIBP accepted all recommendations in this report. We will continue to monitor the implementation of the recommendations.

Current own motion investigation

'Investigation into the implementation of the Thom review recommendations'

In March 2017, the department identified that it had wrongfully detained two Australian citizens for 97 and 13 days respectively. Immediately following the identification of the two Australian citizens in detention, all detainees were reviewed and no further cases of Australian citizens were found. The department then engaged Dr Vivienne Thom to conduct a review of the circumstances of the detention of these individuals. Dr Thom is an independent consultant who conducts inquiries and reviews and advises agencies about governance and integrity matters.

Dr Thom made four recommendations in her review. Some focused on discrete issues including training and decision-making tools, while others looked more broadly at the implementation of recommendations by previous external reviews and quality assurance processes. The department accepted all recommendations made by Dr Thom and has been implementing responses to the recommendations.

In February 2018, we commenced an own motion investigation to examine the immigration detention process holistically and the department's implementation of Dr Thom's recommendations to prevent this situation from occurring again.

The investigation focuses on critical points across the immigration detention process, spanning visa cancellation to release from detention. The investigation is ongoing.

Compliance monitoring

Our Office monitors and inspects the compliance activities of the department and the ABF under our own motion powers.

The Office's oversight occurs through:

- conducting desktop reviews of warrants issued under s 251 of the Migration Act, which allows a warrant to be issued to search premises for unlawful non-citizens and their travel documents and associated documentation

- examining a sample of s 501 removal cases

- observing compliance and removal operations

- analysing six monthly reports on those detained and later released as lawful non-citizens.

Field compliance observations

In 2017–18 the Office observed compliance and removal operations in the following cities:

- Leeton (NSW) 30–31 August 2017

- Sydney 13–15 March 2018

- Melbourne 19–22 March 2018

We observed that ABF officers carry out their duties professionally. However, several issues raised previously with the ABF remained ongoing including officers not properly itemising, receipting or securing the valuables of those detained.

To address our concerns the ABF has been providing its staff with guidance through weekly updates. These updates have included instructions on the receipting of detainee valuables in the field and guidance for interviews. The ABF's Immigration Compliance Branch has also incorporated some of the issues raised by our Office into their new Procedural Instructions.

People detained and later released as 'not-unlawful'

The department provides the Office with six-monthly reports on people who were detained and later released with the system descriptor 'not-unlawful'. This descriptor is used when a detained person is later identified by the department to be holding a valid visa. This can occur due to a number of different factors including, by operation of case law or because of notification issues surrounding visa cancellation or refusal decisions.

For the first half of the 2017 calendar year, the department reported that 13 out of a total of 3,931 people detained (0.33 per cent) were later released as lawful non-citizens compared to 14 out of the 3,679 people detained (0.38 per cent) between 1 July and 31 December 2016. One person was detained for 436 days. The report also detailed the case of two Australian citizens who were unlawfully detained. In response, the department commissioned an independent review into the circumstances that led to the detention of the citizens. The Office is currently investigating the department's implementation of the recommendations arising from this review.

Immigration Detention Reviews

Statutory reporting (two-year review assessments)

Under s 486N of the Migration Act, the Secretary of the department is required to send a report to the Ombudsman regarding each individual that has remained in immigration detention for two years and every six months thereafter. These reports provide details regarding the circumstances of a person's detention including their detention history, case progression, health and welfare, family information and, if relevant, any criminal or security concerns.

Under s 486O, the Office assesses the appropriateness of the detention arrangements of each individual. For the purposes of preparing an assessment, the Office may choose to interview a detainee to gather further information regarding individual and systemic concerns.

The assessments under s 486O can include any recommendations that the Ombudsman considers appropriate. A de-identified version of the assessment is tabled in Parliament by the Minister for Home Affairs with a statement responding to any recommendations. This is subsequently published on our website.

In 2017–18 a total of 1,088 s 486N reports were received from the department, compared to 1,238 in 2016–17. A total of 943 s 486O assessments were tabled, relating to 1,281 individual detainees. Our Office made recommendations in 340 assessments.

These recommendations included both generic recommendations that applied to a cohort of detainees as well as recommendations that were specific to the individual detainees.

Generic recommendations included matters such as the uncertainty associated with the immigration status of individuals who have been returned to Australia from Regional Processing Centres for medical treatment and who, under current policy settings, are not able to have their claims for protection assessed in Australia.

Recommendations that were specific to individual detainees included matters such as placement within the detention network, access to family or support networks, access to appropriate medical treatment, expediting the assessment of an individual's immigration status, consideration of the grant of a visa and consideration of placement in the community.

Issues raised in s 486O assessments

Assessments under s 486O raised a number of issues, including:

- The continued detention (in some cases over seven years) of individuals who have been found to be owed protection and were previously subject to adverse security assessments, who have since been issued qualified security assessments.

- Instances where assessments provided by the International Health and Medical Services (IHMS) provide inaccurate or inconsistent information.

- The continued placement of individuals in immigration detention facilities who have significant vulnerabilities or mental and physical health concerns.

- The impact of family separation on individuals, both within Australia and between Australian and Regional Processing Centres.

- The provision of adequate financial and health care support for individuals released on Final Departure Bridging visas.

- The movement and placement of detainees within the detention network that can impact on their ability to attend specialist medical or court appointments, as well as their access to family support and legal representation.

Detention inspections

The Office undertakes oversight of immigration detention facilities. During 2017–18 we inspected the immigration detention facilities listed in Table 4.

| Immigration Detention or Regional Processing Facility | Location | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Adelaide Immigration Transit Accommodation | Adelaide SA |

Sept 2017 May 2018 |

| Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation | Brisbane QLD |

Jul 2017 Mar 2018 |

| Manus Island Regional Processing Centre | Papua New Guinea |

Aug 2017 April 201816 |

| Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre | Melbourne VIC |

Nov 2017 Jun 2018 |

| Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation | Melbourne VIC |

Nov 2017 Jun 2018 |

| Nauru Regional Processing Centre | Nauru |

Dec 2017 Apr/May 2018 |

| Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre | Christmas Island WA |

Jul/Aug 2017 Jan 2018 |

| Perth Immigration Detention Centre | Perth WA | Jan 2018 |

| Villawood Immigration Detention Centre | Sydney NSW |

Sept 2017 Feb 2018 |

| Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre | Northam WA |

Oct 2017 Feb/Mar 2018 |

Our inspection function is undertaken under the provisions of the Office's own motion powers, in accordance with our jurisdiction to consider the actions of agencies and their contractors.17

The Office provides feedback to each facility after a visit, including any observations and suggestions. We also submit a formal report to the department at the end of each inspection cycle (every six months). The level of cooperation with our Office across the immigration detention network is generally high, with all staff having a reasonable understanding of the role of our Office.

The issues that arose over this reporting period included:

- security-based models in administrative detention

- restrictive practices within detention

- use of force and the Continuum of Force

- placement of detainees in the detention network

- management of internal complaints

- introduction of a service provider operational electronic records management system

- programs and activities

- management of detainee property

- access to mobile phones.

Security-based model of administrative detention

The Migration Actenables the detention of unlawful non-citizens, such as those who enter or remain in Australia without a valid visa. Detention has been mandatory for all unauthorised maritime arrivals since 199418 and for people whose visas have been cancelled on character grounds since 2014.19

While placement in an immigration detention facility is mandatory for certain cohorts, it is administrative in nature–an individual is detained for the purpose of conducting an administrative function rather than as an end state of the criminal justice system.

The operations of an immigration detention facility are not supported by a legislative framework. The reliance on an administrative rather than a legislative framework to underpin the operations of the immigration detention network remains a concern for our Office.

During 2017–18 we noted an increasing emphasis on a security-based operational model. While the increasing numbers of detainees with histories of violent or antisocial behaviours require an increased focus on safety and security, we remain concerned that this may be at the expense of a focus on the welfare of detainees. This is not to imply that welfare should be the primary consideration when determining the management program for a detainee, but rather, both welfare and security need to be in balance to achieve a fair and reasonable outcome for all concerned.

Security-based operational models such as the 'controlled movement model' are the most restrictive of all operational models. Detainees can be restricted to accommodation areas and unable to move freely between common areas. Whilst there are circumstances where this model is appropriate, such as in high security compounds, facilities where detainees are vulnerable to coercion or intimidation, or immediately following periods of unrest, this model should not be the first preference for an administrative detention environment.

Placement of detainees within the network

The Australian Government, through the ABF and its respective facility Superintendents, has a duty of care to all detainees.20 In order to fulfil the duty of care, detainee placements within a facility and the broader network should be made by considering the full set of circumstances of a detainee.

The Office remains concerned that placement decisions do not apply adequate weighting to detainee circumstances such as court appearances, specialist medical treatment and family considerations. We acknowledge that the risk assessment of a detainee is a significant consideration, however it would appear that on occasions little consideration is given to other factors.

While placement will be driven by operational needs, in particular bed space in East Coast facilities, this should not be the sole basis for placing a detainee on Christmas Island or at Yongah Hill. Where the facility is remote and isolated, it is essential that placement decisions take account of all relevant considerations and information.

Of equal concern to the Office is an inaccurate risk assessment or a poorly analysed assessment that is applied without consideration of individual circumstances.

Determining that all detainees who have a criminal history involving violence exhibit high-risk behaviour, can result in unfair outcomes. Good decision-making requires consideration of relevant factors such as the type of behaviour, the age of the detainee at the time of the incident, the passage of time since the incident, the circumstances that generated the behaviour and the relevance to the current environment. Positive reinforcement of good behaviour is negated in an environment where the negative behaviours of the past consistently dictate the use of restraints or placement in remote facilities.

Towards the end of this reporting period, we have noted an increasing willingness to provide a more thorough analysis to the information upon which the risk assessment is based. The improvement in the provision of information held externally to the department has assisted in this, and the ABF continues to work with these sources to maximise the effectiveness and accuracy of the risk assessments. We have been advised that the placement tool used by the department is intended to address these issues and take into account the detainee's personal circumstances, family and community linkages and legal or medical circumstances.

As the placement processes, including the application of the revised placement tool, have evolved during this reporting period, we have noted that the decisions relating to the placement of a detainee within the network have improved, with decisions being made in a somewhat more holistic manner. We will continue to monitor this throughout 2018–19 as the placement modelling and risk assessment processes continue to evolve.

Restrictive practices in detention

The department and its service providers have a duty of care to both detainees and their staff to protect them from violent or aggressive behaviours and the ongoing risk of damage to people or property.

We acknowledge that there are occasions where for the good order, security and welfare of the facility, a detainee may need to be placed in restraints or moved to a more restrictive environment. Since the implementation of the Minister for Immigration and Border Protection Direction 65, and the subsequent increase of detainees with histories of violent or antisocial behaviours, we have noted an increasing use of these restrictive practices across the immigration detention network.

Without a legislative framework to underpin these practices, the department must rely on its administrative framework to support operating in this environment. We are concerned that the administrative processes underpinning these practices are not as robust as they should be and have identified shortfalls associated with the:

- use of mechanical restraints when transferring detainees

- use of the controlled movement operational model as the standard operational model

- placement of detainees in behaviour management programs.

Where there is no legislative framework to support the use of restraints or placement in contained environments, the administrative framework must support the principles of procedural fairness, provide independent points of review and appeal, as well as the appropriate mitigation against the risk of such practices becoming punitive in nature.

We acknowledge that the ABF has taken steps to tighten the administrative frameworks surrounding the use of high care accommodation. The ABF has also adopted practices that provide procedural safeguards for detainees placed in behaviour management regimes. We consider that this area provides a significant risk to the department and we encourage them to continue to strengthen the administrative framework that supports these critical operational areas.

Use of Force and the Continuum of Force

Over the inspection cycles during 2017–18, we have noted an increasing use of unplanned force21 by the department when dealing with detainees. While it is accepted that use of force can be necessary to protect the individual, other people or property, we are concerned that the review of incident management records did not reflect the use of de-escalation techniques prior to the application of force.

On occasions, we perceived that some operational staff considered the application of physical force to address non-compliant behaviour as the start-point rather than the mid-point of the continuum. This suggests a continued need for training in this area.

In facilities where additional training in negotiation and de-escalation skills have been undertaken, the Office has observed an overall improvement in the method of engaging with detainees. That is, the first option is to approach a situation with a view to achieving a negotiated outcome first, with the use of force only considered as a last resort.

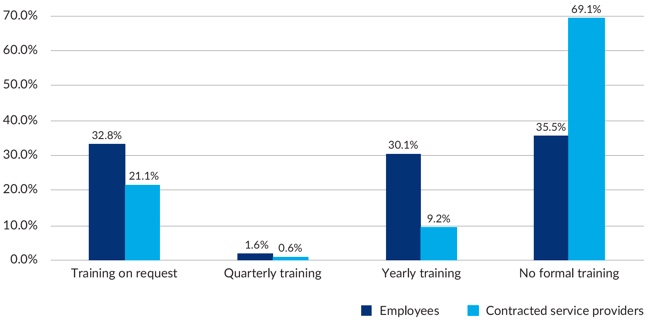

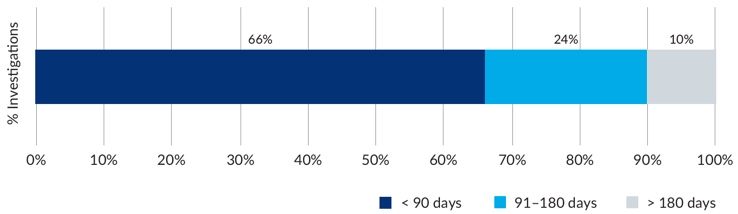

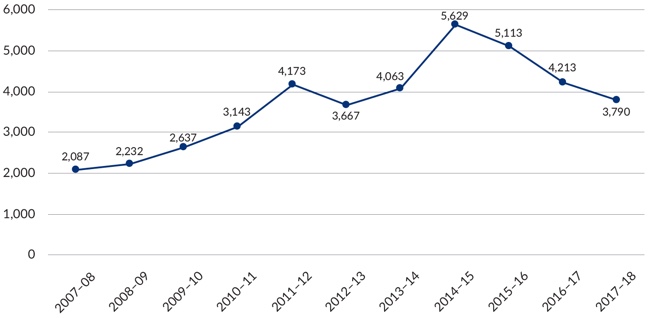

Management of internal complaints

One of our primary focuses for 2017–18 was the management of internal complaints by the ABF and its service providers. Good complaint-handling requires a systematic approach that is timely, appropriate and responsive.22 Overall, the standard of complaint-handling across the immigration detention network was reasonable with the suggestions made by the Office for improvements being implemented in a number of facilities.

During 2017–18 we undertook a detailed assessment of the internal complaint-handling practices across the immigration detention network. Despite an overarching standard operating procedure for the management of complaints being introduced by the ABF in September 2016, we have noted that an inconsistency in the manner or methods applied to the management of complaints made against the department and/or their service providers remains. We will continue to closely monitor this issue throughout 2018–19.

Programs and activities

Where detainees fail to engage with programs and activities, it is more than likely that they will experience deteriorating levels of mental health and an increased likelihood of self-harm or other non-compliant behaviour.23

Engagement with programs and activities should be meaningful and involve activities that the detainees wish to undertake, rather than simply being carried out to alleviate boredom. We noted that activities that focused on physical fitness, life skills (such as cooking, resume-writing and job interview skills) and adult art and craft, were more likely to be considered meaningful by detainees and attract higher participation rates. Activities that were considered to be juvenile appeared to generate participation that was based on avoiding boredom rather than enjoyment.

We acknowledge there has been a significant change in the types of activities offered to meet the needs of the changing cohorts within centres. However, additional effort needs to be made to address the needs of people who have been educated in the Australian education system.

Introduction of service provider operational electronic records management system

In November 2016, Serco Immigration Services introduced an electronic record-keeping and process management tool. The system was introduced to streamline and capture operational activities such as welfare checks, attendance at activities, detainee property management and the compilation of incident management documents.

Despite a number of ongoing connectivity and other operation alignment issues, we have noted an overall improvement in the quality of record-keeping with the use of this system. We will continue to monitor the impact that this system has on the quality of reporting within the immigration detention network, especially in those areas where the tool does not reflect the current departmental or service provider policies. This is apparent in the management of detainee property where the tool has generated a process that is not reflective of the current guidelines.

Management of detainee property

The management of detainee property is a key area of interest for the Office. During this reporting period we noted an overall general improvement across the network. The introduction of an electronic record-keeping and process management tool has improved the overall management of detainee property, however we have noted a number of inconsistencies that will be addressed as the property management guidelines are amended to include the new electronic management system.

There are outstanding complaints and associated issues relating to the compensation for items lost or damaged in the November 2015 unrest on Christmas Island. During the unrest, the secured storage facility used for the storage of detainee intrust property was ransacked and detainees' personal property removed. This incident and the subsequent difficulties that the department has experienced in compensating detainees for the loss of their intrust property reinforces the importance of detainee property being accurately recorded.

The new electronic property management system that includes both photographs and a detailed written description should address a number of the issues arising from this incident including:

- correctly identifying lost property

- providing appropriate levels of compensation for items that cannot reasonably be returned to a detainee on departure.

Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT)

What is OPCAT?

Australia ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in December 2017. OPCAT is an international agreement aimed at preventing torture and mistreatment through the use of a proactive inspection regime in places where people are deprived of their liberty.

Compliance with OPCAT involves the inspection by state and territory inspectorate bodies of places of detention including prisons, juvenile detention centres and psychiatric facilities. The implementation of OPCAT is occurring over a three year period.

The National Preventive Mechanism Coordinator

Our Office has been appointed as the National Preventive Mechanism (NPM) Coordinator to facilitate and coordinate the Commonwealth, state and territory oversight arrangements. This function commenced on 1 July 2018.

The Commonwealth NPM for Commonwealth Primary Places of Detention

Our Office has also been announced as the NPM Body for Commonwealth places of detention including immigration detention facilities, Australian Federal Police cells in the External Territories and military detention facilities.

Stakeholder engagement

While the implementation towards OPCAT will occur over a three year period, we are engaging with existing oversight bodies domestically and considering best practices from overseas. We are also engaging with the civil society, including participating in conferences and forums.

Churchill Fellowship

In October 2017, Mr Steven Caruana was awarded a Winston Churchill Memorial Trust Fellowship. This enabled him to research best practice inspection methodologies for oversight bodies with a focus on OPCAT. As part of the Fellowship, he visited the United Kingdom, Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, Malta, Greece and New Zealand to meet with inspection agencies, leading academics and notable anti-torture non-government organisations.

The learnings and insights arising from research undertaken as part of the Fellowship will assist our Office in its role as the NPM Coordinator.

Law Enforcement Ombudsman

The Office has a comprehensive role in the oversight of the Australian Federal Police (AFP). When performing functions in relation to the AFP, the Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman may also be called the Law Enforcement Ombudsman.

These functions include:

- assessing and investigating complaints about the AFP

- receiving mandatory notifications from the AFP regarding complaints about serious misconduct involving AFP members, under the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (AFP Act)

- statutory reviews of the AFP's administration of Part V of the AFP Act.

Complaints

In 2017–18, we received 258 complaints about the AFP, which was an 11 per cent decrease from 2016–17, of which we investigated 36.

In the majority of cases we declined to investigate complaints if the person had not first complained to the AFP. In those instances, we referred them back to the AFP.

Other reasons for not investigating included:

- another oversight body being the more appropriate agency to handle the complaint

- the matter had already been to court

- the complaint lapsed due to the complainant not providing us with certain information

- the complainant had insufficient interest in the matter, or

- complaint withdrawal.

When we investigate a complaint we first look at how the AFP handled the issue and assess the particulars of the matter against the relevant law, policy and practice.

Four of the complaints we investigated were finalised because an appropriate remedy was provided by the AFP. However, the majority of complaints were finalised on the grounds that further investigation was not warranted given circumstances. This usually meant that the issue, actions and decisions of the AFP were open to be made and not unreasonable.

In resolving and finalising nine complaint investigations in 2017–18, we made suggestions to the AFP with a view to remedying individual complaints and for future improvements.

Our Office also conducted two reviews of the AFP's administration of Part V of the AFP Act and published a report on the results of previous reviews.

As part of this process we engaged with the AFP Professional Standards (PRS) to discuss a number of reforms that are being implemented across PRS. We also met with representatives from the AFP Safe Place team to discuss their management of complaints under Part V of the Act. This area was established to provide support to complainants and to investigate sexual harassment and abuse, following an independent review of the organisation by former Sex Discrimination Commissioner, Elizabeth Broderick.

Inspections of covert, intrusive or coercive powers

Oversight activities

In 2017–18, the Office performed oversight functions under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979, the Surveillance Devices Act 2004, Part IAB of the Crimes Act 1914, the Fair Work (Building Industry) Act 2012 and the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016. This legislation grants intrusive, and often covert, powers to certain law enforcement agencies. Our role is to assess agencies' compliance with the above legislation.

We are required to inspect the records of enforcement agencies and report to the relevant Minister (who is responsible for administering the Commonwealth Acts we oversee) on the activities agencies have undertaken pursuant to each Act. Reports to the Minister are subsequently tabled in Parliament.

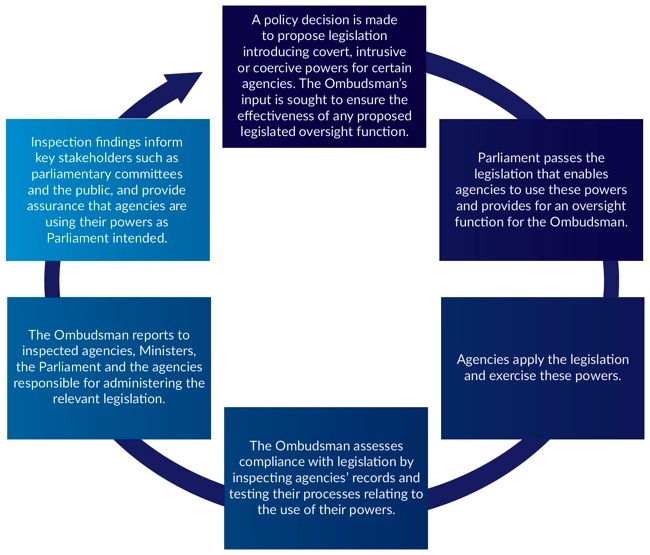

Figure 7 – The independent oversight process

Law Enforcement agencies subject to inspections by the Office

- Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity

- Australian Competition and Consumer Commission

- Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission

- Australian Federal Police

- Australian Securities and Investments Commission

- Western Australia Corruption and Crime Commission

- Crime and Corruption Commission of Queensland

- Department of Home Affairs

- Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission (Victoria)

- New South Wales Independent Commission Against Corruption

- South Australia Independent Commissioner Against Corruption

- Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (NSW)

- New South Wales Crime Commission

- New South Wales Police Force

- Northern Territory Police Force

- Queensland Police Service

- South Australia Police

- Tasmania Police

- Victoria Police

- Western Australia Police

Non-law enforcement agencies subject to inspections by the Office

- Australian Building and Construction Commission

- Fair Work Ombudsman

| Function | Number of inspections or reviews |

|---|---|

| Inspection of telecommunications interception records under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 | 6 |

| Inspection of stored communications–preservation and access records under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 | 18 |

| Inspection of metadata records under the Telecommunications (Interceptions and Access) Act 1979 | 20 |

| Inspection of the use of surveillance devices under the Surveillance Devices Act 2004 | 10 |