Part 5 - Public Interest Disclosure Scheme

Part 5—Public Interest Disclosure Scheme

This chapter comprises our annual report on the operation of the Public Interest Disclosure Act 2013 (PID Act) as required by section 76 of the Act.

The Office oversees the operation of the Public Interest Disclosure (PID) Scheme (the scheme), established under the PID Act. The scheme promotes the integrity of the Commonwealth public sector by providing for the reporting and investigation of wrongdoing and the protection of whistleblowers.

The Office has three primary functions under the scheme:

- allocation of disclosures and investigation of complaints

- delivery of education and awareness programs

- annual reporting on the scheme's operation.

The Inspector-General of Intelligence and Security (IGIS) has oversight of the six intelligence agencies subject to the scheme38 and has the same allocation, investigative and education functions.

This report has been prepared with the assistance of the 178 agencies covered by the PID Act. We would like to acknowledge their efforts in collecting the data required for this report.

Key elements of the scheme

The scheme is designed to be accessible. The low threshold for making a disclosure is intended to encourage officials to come forward and report wrongdoing. The protections under the PID Act apply to disclosures that:

- are made by a current or former public official

- are to an authorised recipient

- involve 'disclosable conduct'.

'Public official' is broadly defined and includes contracted service providers and subcontractors. Similarly, 'disclosable conduct' captures a broad range of conduct, such as the breach of a law or of the Australian Public Service (APS) Code of Conduct. These broad definitions mean the scheme attracts reports of wrongdoing across a wide cross section of agencies and activities. Agencies must investigate a PID unless certain circumstances apply, such as the matter having previously been dealt with through another process. At the conclusion of an investigation, agencies must provide disclosers with an investigation report that explains the findings of the investigation, and any actions taken or recommendations made. Disclosers can make a complaint to the Office or IGIS if they are dissatisfied with an agency's handling of their PID.

PIDs at a glance

In 2018–19, there were 457 PIDs received across the Commonwealth, compared with 737 last year. The decline in numbers is largely attributable to a large reduction in PIDs at one major agency (Australia Post). It may also be explained by advice from this Office that agencies should report on the number of disclosures they have assessed as PIDs (rather than the number of disclosures received). However, given that the number of disclosures that were assessed as not meeting the PID threshold was similar to last year (342 disclosures compared with 354 last year) the results indicate a decline in the overall number of disclosures. This may be attributable to clearer information on some agencies' websites about the application and scope of the PID Act.

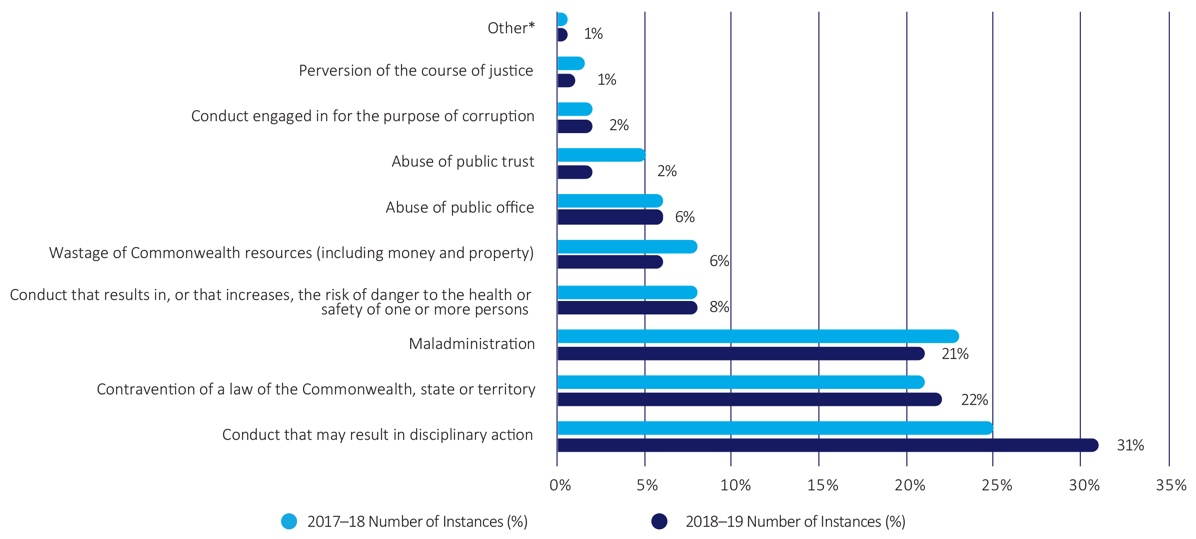

A single PID may involve multiple allegations of disclosable conduct. Of the PIDs made this year there were 792 alleged instances of disclosable conduct.39 As in previous years, the most common types of alleged disclosable conduct were 'conduct that may result in disciplinary action', 'breach of a law' and 'maladministration'. Given the broad based nature of these descriptions, they cover a wide range of actions and conduct. Conduct that may result in disciplinary action would generally relate to conduct that might contravene internal codes of conduct.

Figure 16—2018–19 Disclosures at a glance

Figure 17—Allegations of disclosable conduct–FY comparison

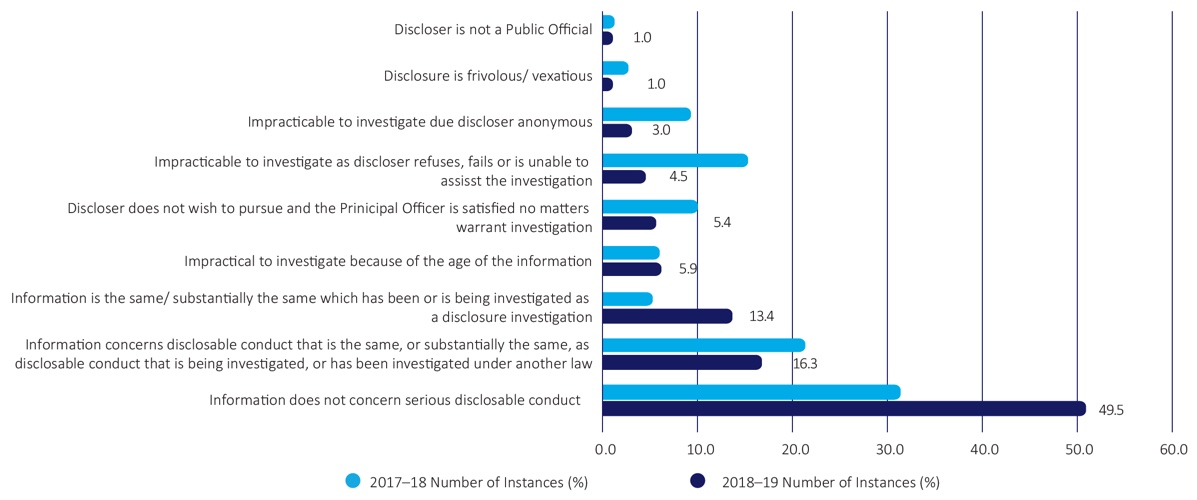

Agencies may decline to investigate a PID, or decline to further investigate, for a range of reasons. This year agencies declined to investigate (in full or part) 180 PIDs. The most common reason was because the PID did not concern serious disclosable conduct. The PID Act provides that the seriousness of alleged action or conduct is not relevant when deciding whether the disclosure is a PID, but may be relevant when deciding whether an investigation is required. While these results may indicate an improved understanding among agencies of the PID Act, we propose to monitor the issue given the increase in the number of times this ground was identified as the reason for not investigating all or part of a PID.

Figure 18—Use of s 48 – FY comparison

Investigation outcomes

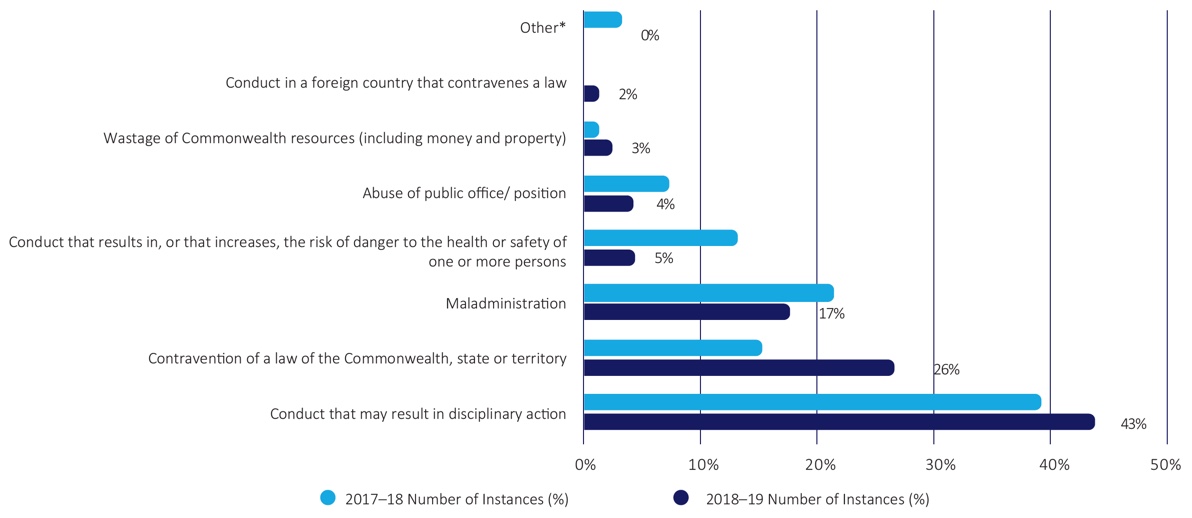

A total of 289 PID investigations were finalised this year. 84 investigations resulted in one or more findings of disclosable conduct, and 146 resulted in at least one recommendation that particular action be taken.

Figure 19—Findings of disclosable conduct – FY comparison

We remind agencies at our regular PID forums that a PID investigation that does not result in a finding of disclosable conduct may nonetheless identify an opportunity to mitigate potential risks of wrongdoing or improve agency practice and procedure.

Agencies reported a range of outcomes and actions following investigation, including:

- standardisation of procurement training materials

- staff counselling regarding adherence to agency practices and procedures

- inclusion of formal risk assessments as part of major change activities

- review of internal complaint-handling policies and procedures.

On three occasions agencies contacted the police because there were reasonable grounds to suspect that a disclosure included evidence of an offence.

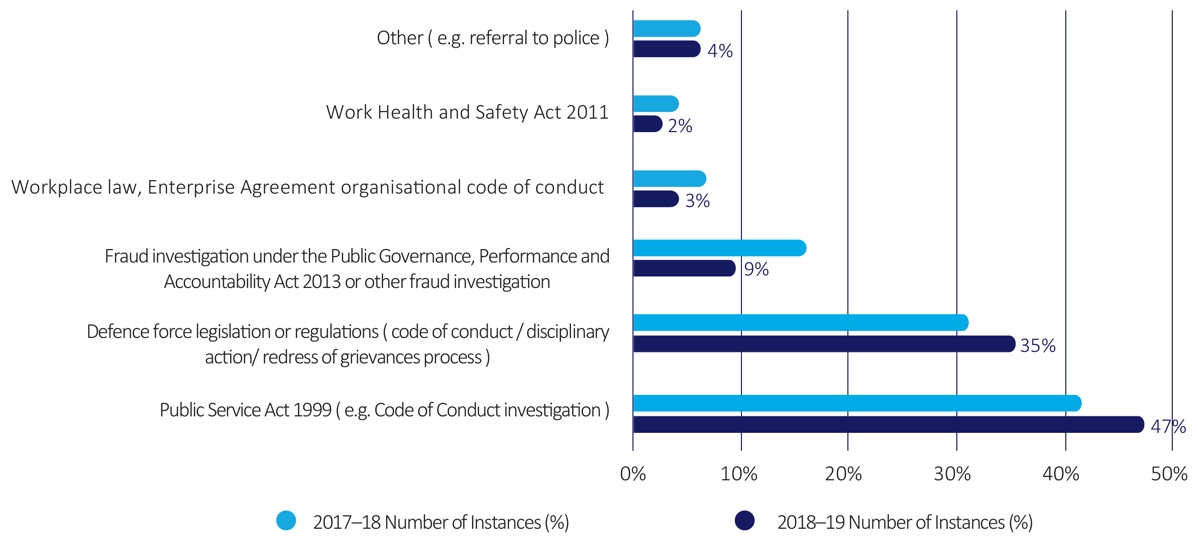

The PID Act also enables agencies to recommend investigation of a PID under another law. Common areas for referral include the Public Service Act 1999 (for investigation of Code of Conduct matters), Defence Force legislation, Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (for fraud matters) and Workplace Health and Safety legislation. This year, 94 recommendations for referral were made. Consistent with last year's results, the majority involved a referral for investigation under the Public Service Act.

Figure 20—2018–19 Referrals to other investigative mechanisms

For full details of the number of PIDs received, the kinds of disclosable conduct alleged, the number of disclosure investigations and the actions taken in response to recommendations, see Appendix 7.

Who is using the scheme?

Usage of the scheme was broadly consistent with previous years. The majority of PIDs were made by current or former public officials, with a slight increase in the number of PIDs made by this cohort (91 per cent this year compared with 84 per cent last year). The number of disclosures made by contracted service providers remained relatively constant at five per cent of disclosures, and there was a decline in the number of disclosures from deemed public officials40 (four per cent this year compared with 12 per cent last year).

Given the broad use of contracted service providers across the Commonwealth it is possible that they remain under-represented in the overall numbers of disclosures.

Awareness raising and training

Agencies reported providing a variety of PID-related information and training including mandatory induction programs, intranet or employee handbook materials, and all staff communications. Consistent with last year's results, around a third of agencies provide formal PID training to their employees on a yearly basis, with 67 per cent of agencies providing either no formal training or providing training only upon request.

As with last year, most agencies reported providing no formal PID training to contracted service providers. Many agencies however report providing PID information to contracted service providers via other means, such as during the procurement and contracting process, via access to the agency's intranet, or through informal distribution of information. Since the number of disclosures from this cohort is unchanged, and lack of awareness may be a barrier to reporting, we will continue to remind agencies of the need to ensure awareness of the PID scheme among this group.

Authorised officers

A public official may only make a disclosure to an authorised officer,41 to their supervisor or to the agency's principal officer. As with last year, most disclosures were made to authorised officers. The number of disclosures to authorised officers did decrease slightly (80 per cent, compared with 88 percent in the previous year) and more disclosures were made directly to principal officers (12 per cent compared with five per cent in the previous year). The number of disclosures made to supervisors remained steady (eight per cent compared with seven per cent last year).

| Staff numbers | Average number of authorised officers |

|---|---|

| <50 | 2 |

| 50–250 | 2 |

| 250–1,000 | 5 |

| 1,000–10,000 | 8 |

| Over 10,000 | 14 |

We encourage agencies to appoint authorised officers at a range of levels. However, the substantive level of most authorised officers remains high with 50 per cent of authorised officers at senior executive level and 40 per cent at executive level. We will continue to encourage agencies to consider the relative seniority of authorised officers noting that it may create a barrier to reporting. We will also undertake some further analysis of the number of authorised officers in agencies of comparable size, noting that the number of authorised officers can vary significantly (e.g. the number of authorised officers within agencies with 10,000 or more employees ranged from 3 to 24).

Timeliness

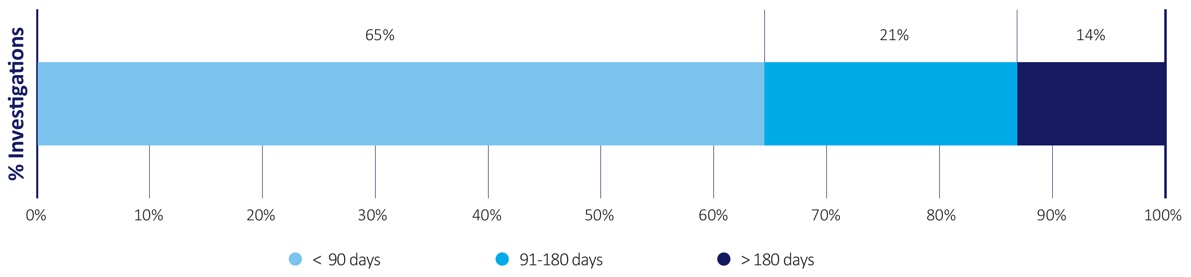

The PID Act imposes a 90 day timeframe on investigations, subject to possible extension from the Office or IGIS where there are reasonable grounds. If an investigation is not completed in time and an extension is not granted, the discloser may in certain circumstances seek redress by disclosing the information externally. Most investigations were completed within 90 days (65 per cent) with 21 per cent taking between 90-180 days and 14 per cent taking more than 180 days.

The Office received 171 requests for extension of time, of which 161 were granted. As a result of the guidance we published in 2018, agency estimates of the time needed to complete an investigation appear to be more considered. In 2019–20 we propose to monitor agencies' performance against advice in our policy that they apply for an extension well before the 90 day timeframe is complete, and to keep disclosers informed of an investigation's progress.

Figure 21—Investigation timeframes

Reprisal

Disclosers who believe they have been subject to reprisal are encouraged to raise the issue with their agency. Agencies are expected to investigate claims of reprisal and, if appropriate, refer the matter to the police or other oversight agency. Disclosers may also contact the Office if they are dissatisfied with the agency's handling of their reprisal claim.

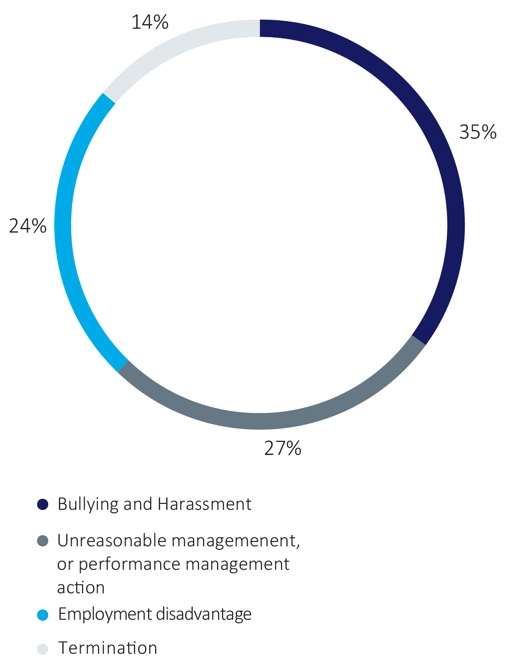

In 2018–19, Commonwealth agencies reported a total of 17 claims of reprisal. The types of conduct alleged included bullying and harassment and unreasonable management or performance management action. Agencies reported that, following investigation, two reprisal claims were substantiated. The Office also received 18 enquiries or complaints directly from disclosers raising concerns about reprisal. Disclosers variously elected to make a PID regarding the reprisal action, make a complaint to our Office, or await the outcome of the agency's investigation report. Following feedback from our PID forums, the Office will publish further guidance to agencies in 2019–20 about managing the risk of and investigating concerns about reprisal.

Figure 22—Claims of reprisal

Complaints

The Ombudsman and IGIS can review agencies' handling of PIDs to assess whether their actions are reasonable and whether agencies are complying with the PID Act and their own PID procedures.

In 2018–19 the Ombudsman received 52 complaints about agencies' handling of public interest disclosures, an increase of 18 per cent from the previous year. The majority of complaints related to the process and outcome of disclosure investigations.

Of the 52 complaints about agencies' handling of disclosures, the Ombudsman investigated 21 matters. Common complaint themes were:

- consideration of evidence and selection of witnesses

- decisions not to investigate where the matter had previously been investigated, or because the conduct is not of a serious nature

- decisions that a disclosure does not concern 'disclosable conduct' and is not allocated for investigation

- allegations that an investigation was affected by bias or a conflict of interest.

Of the 21 matters investigated, we made comments or suggestions about improving agency processes in five cases. In two additional investigations, the agency elected to initiate further investigation of the disclosure in response to our inquiries.

CASE STUDY

A discloser complained to us about an agency's handling of an investigation. Amongst other things, the discloser said the investigator failed to consider information relevant to the disclosure and failed to interview relevant witnesses. The discloser also alleged that the investigation was affected by a conflict of interest, as the investigator was a senior officer in the business area where the disclosable conduct was alleged to have occurred.

We requested some information from the agency about its assessment of the potential conflict of interest and the investigator's selection of witnesses. The agency responded advising that it considered the circumstances warranted the matter being referred for a new investigation by an independent investigator.

CASE STUDY

We investigated a complaint about an agency's decision to finalise an investigation under s 47(3) of the PID Act. Section 47(3) of the PID Act allows agencies to consider whether a disclosure should be investigated under another law. The agency had referred the matter to an internal, specialist area for investigation and had finalised the PID investigation on that basis.

We identified a number of flaws with the agency's investigation, including its application of s 47(3). We noted that s 47(3) of the PID Act is designed to enable agencies to refer matters for investigation under another specific law, such as the Public Service Act 1999, Fair Work Act 2009 or Workplace Health and Safety Act 2011. We took the view that the agency's decision to refer a matter to an internal area, which did not have investigative powers under a Commonwealth law, was not a proper application of the PID Act. We suggested that, unless there is a specific legislative mechanism under which a matter can be investigated and this mechanism is more likely to ensure the matter is properly investigated, agencies should investigate the matter under the PID Act. We also noted that it would have been open to the agency, when investigating the PID, to seek specialist advice from particular areas if required.

The agency agreed with our views and undertook to reinvestigate the disclosure, review its PID guidance material and arrange training for its Authorised Officers and Principal Officer delegates.

CASE STUDY

A discloser complained to us about an agency's decision not to investigate their disclosure. During our investigation, the agency confirmed that the decision was made by an authorised officer, who had also been delegated the principal officer's power in s 48 of the PID Act to decide whether a disclosure should be investigated. We acknowledged that this was not specifically precluded by the PID Act, but noted the risk of an authorised officer taking into account irrelevant considerations in the initial assessment of a disclosure under s 43 of the PID Act, where that officer would ultimately be responsible for deciding whether or not to investigate that disclosure. We also noted that an authorised officer may receive information in the course of a PID investigation that could potentially amount to a new internal disclosure, and would then need to be assessed in their capacity as an authorised officer. We considered that it was preferable for the functions of an authorised officer and an investigation officer to be delegated to different individuals as far as possible, and performed by different individuals in the context of a single disclosure. The agency accepted our comments and recommendations on this issue.

Ombudsman investigations

The PID Act enables disclosers to make a disclosure directly to the Office if they have reasonable grounds to believe the Office should investigate. Generally speaking, the agency to which the disclosure relates is best-placed to investigate a disclosure. However, the Office may consider investigating a matter directly if satisfied that the agency is unable to properly investigate or respond to the disclosure. This year, the Office received 63 disclosures about other Commonwealth agencies, down from 78 last year. Of the 63 disclosures, 46 were assessed as PIDs. The majority were allocated to the relevant agency for investigation. We accepted one PID for investigation and allocated a further four to the Australian Public Service Commission as the disclosures fell within its jurisdiction under the Public Service Act 1999.

We completed 10 disclosure investigations this year, with a number of these having commenced in the previous reporting period. Of the investigations completed, none resulted in a finding of disclosable conduct, however the Office made recommendations to agencies in three cases. Recommendations focused on agencies providing clear reasons for decisions, the need to undertake risk assessments and manage the risk of reprisal, and ensuring agency policies are up-to-date.

IGIS investigations and complaints

Throughout the year the IGIS provided assistance and advice to officials within the intelligence agencies. This Office assisted the IGIS, where needed on the operation of the PID Scheme and the performance of their functions under s 63 of the Act.

The IGIS received five direct disclosures, all of which related to Australian intelligence agencies. Of these, four were investigated by the IGIS under the Inspector General of Intelligence and Security Act 1986 (IGIS Act). Two of these investigations remained open at the end of the reporting period. The IGIS exercised discretion not to investigate, or investigate further, under s 48 in one case.

The six security and intelligence agencies which form the Australian Intelligence Community received one PID, which was completed under s 51 of the PID Act.

The IGIS did not receive any complaints about the handling of PIDs this financial year.

Education and awareness

This year we launched an Investigation Officers forum to complement our Authorised Officers forums. We delivered authorised officer forums to 235 representatives from a large cross-section of agencies. This represents almost double the number of representatives attending our forums last year and feedback from attendees was very positive.

We have continued to emphasise the themes of trust, communication and action as critical to the successful operation of the PID scheme.

Figure 23—The three core themes delivered at PID forums

Building on observations from previous years and based on our complaint investigations, discloser dissatisfaction most commonly arises because a discloser has not been kept informed of the progress of an investigation, the investigation of a PID has not been well explained, or the possible outcomes of a PID investigation have not been well understood as opposed to other remedies which may be available.

In response, this year we have encouraged agencies to consider nominating officers who can provide information on the broad range of complaint resolution and integrity mechanisms that exist including PID, to ensure that public officials are properly informed of the full range of options available to them. We have also encouraged agencies to consider engaging with disclosers once a PID report has been provided to respond to any queries or concerns.

In 2018–19 the Office responded to 237 telephone and email enquiries from agencies and disclosers, a nine per cent increase from last year, and we received 14,900 visits to our content pages on our website. Following a refresh of the Office's website we will be examining ways to further improve the accessibility and relevance of our PID information.

Given the link between PID and broader integrity measures, this Office made submissions on the operation of the PID Act to the inquiry conducted by the Senate Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs concerning the National Integrity Commission Bills. The Office also made a submission concerning the PID Act to the Attorney-General's Department as part of consultation on the development of a Commonwealth Integrity Commission.

Footnotes

38 Australian Security Intelligence Organisation, Australian Secret Intelligence Service, Australian Signals Directorate, Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation, Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments

39 This refers to allegations of disclosable conduct prior to an investigation being undertaken.

40 Agencies may deem a person to be a public official in certain circumstances. Agencies generally use this approach to investigate PIDs from non-public officials who may have special or inside information about wrongdoing in an agency.

41 A person appointed by an agency's principal officer to receive disclosures. Principal Officers are required to ensure there are sufficient numbers of authorised officers to ensure they are readily accessible to public officials in their agency.