Part 4 - What we do

Part 4—What we do

- COMPLAINT MANAGEMENT

- OVERSIGHT OF GOVERNMENT AGENCIES

- OVERSIGHT OF LAW ENFORCEMENT

- OPTIONAL PROTOCOL TO THE CONVENTION AGAINST TORTURE AND OTHER CRUEL, INHUMAN OR DEGRADING TREATMENT OR PUNISHMENT

- OUR ROLE AS AN INDUSTRY OMBUDSMAN

- WORKING WITH INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS

Complaint Management

Complaints to our Office

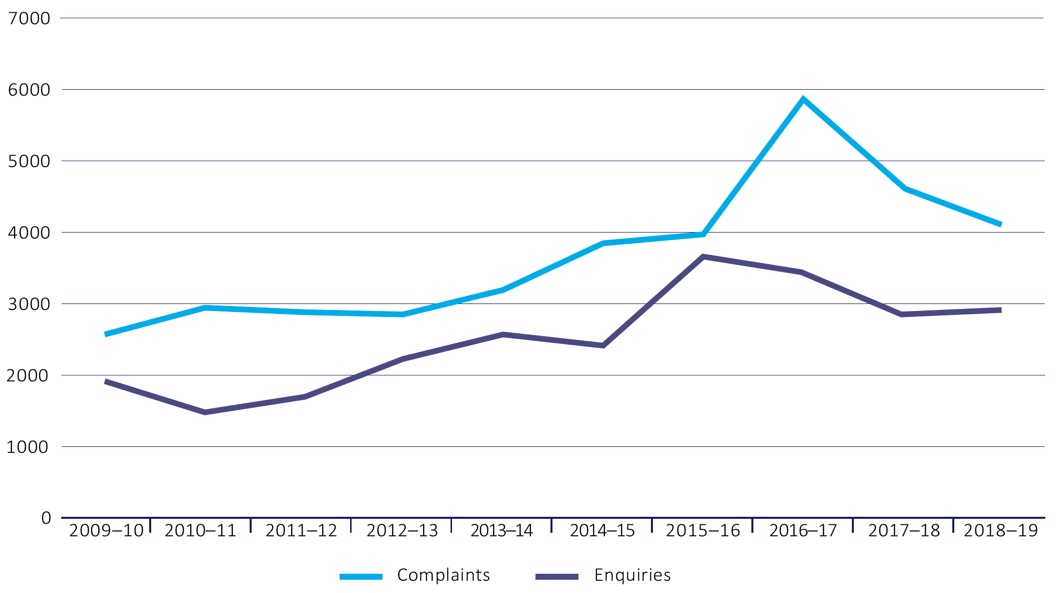

Public contact

In 2018–19 we received 50,237 contacts3 from the public, compared to 47,557 contacts in 2017–18. This is a 5.6 per cent increase.

Of the total contacts received, 37,388 were complaints within our jurisdiction (compared to 38,026 in 2017–18). Of these complaints, 49.8 per cent fell within our parliamentary complaints jurisdiction (complaints about Commonwealth and ACT Government agencies) and 50.2 per cent related to our industry complaints jurisdiction (such as VET Student Loans, overseas students, and private health insurance matters).

The Office finalised 34,322 in-jurisdiction complaints in 2018–19, a 2.9 per cent decrease compared to 2017–18. 18,748 of these finalised complaints were about government agencies and 15,574 were about industry bodies.

In 2018–19 the Office received 11,673 enquiries, a 37.8 per cent increase compared to 2017–18. Enquiries can include requests for information from our Office (such as a media enquiry, a Freedom of Information application or a request for one of our reports) or can relate to matters not within our jurisdiction (for example, complaints about state or territory government matters, telecommunications companies or financial service providers). In 2018–19, this number includes 3,417 submissions received from the public as part of our own motion investigation into the administration of the Defence Force Retirement and Death Benefits scheme. See page 62 for more information about this investigation.

The Office also received 1,176 public contacts related to the specific programs we deliver. These include reports of abuse in the Australian Defence Force, public interest disclosures, and applications for review of FOI decisions made by ACT Government agencies. More information about each of these programs is provided later in this section. Information about our activities as the ACT Ombudsman is provided in our separate ACT Ombudsman annual report.4

Receiving complaints

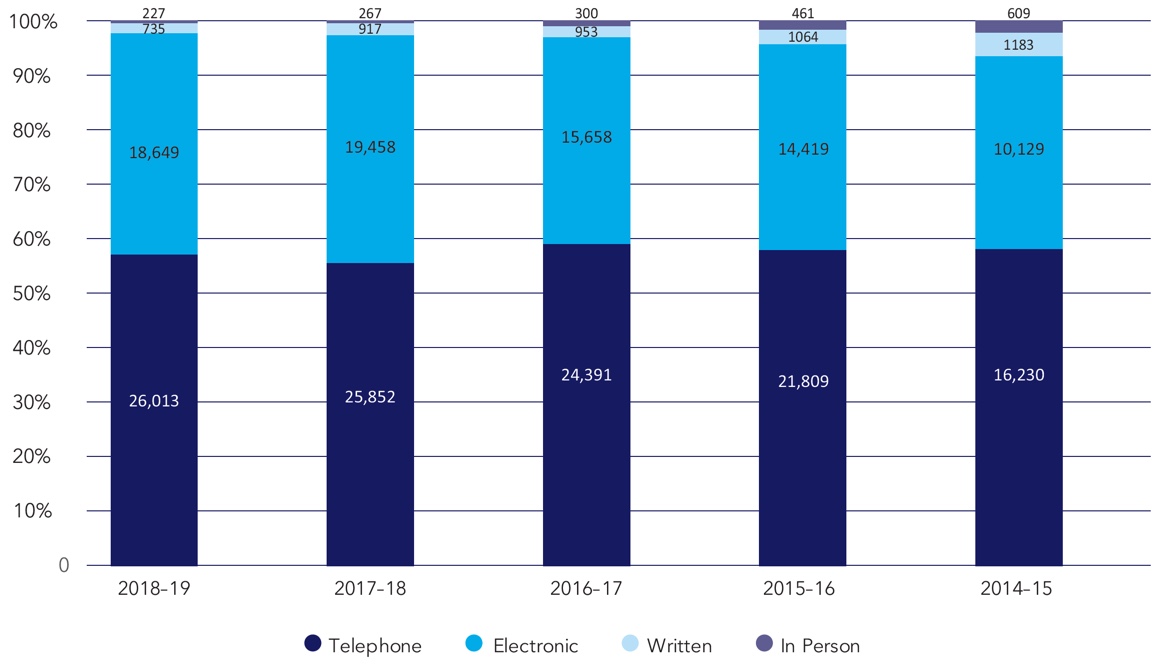

The Office receives complaints through a variety of methods. Telephone remains the most popular way to make a complaint. In 2018–19, we revamped our website to make it easier for people to find information about our services, including circumstances in which a person might be better placed pursuing their complaint through a different organisation. A priority for 2019–20 is to further improve our website to make it easier to lodge complaints online.

Figure 2—Trend in how contacts and complaints were received over the last five years

Note: For the purposes of comparison on previous years, Figure 2 excludes DFRDB contacts and program specific matters.

Complaints about government agencies

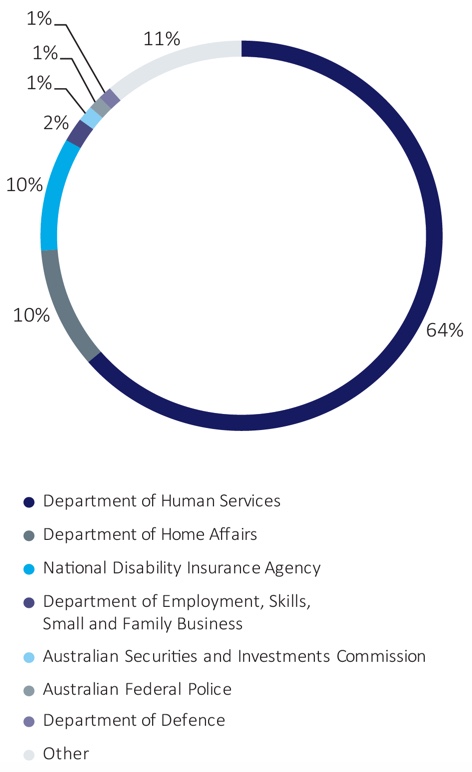

In 2018–19 we received 18,161 complaints about Commonwealth Government agencies, a decrease of five per cent on the 19,121 received in 2017–18. We also received complaints about private sector organisations through our industry ombudsman roles.

Of the complaints about commonwealth entities, 84 per cent were about three agencies: the Department of Human Services, including Centrelink and Child Support programs (11,652), the Department of Home Affairs, including the Australian Border Force (1,824)5 and the National Disability Insurance Agency (1,711).

Figure 3—Complaints received by government agency6

More information about the issues raised in relation to these agencies is provided later in this section.

Handling complaints

In 2018 the Office restructured its parliamentary complaint-handling operations to deliver a more efficient and effective complaint-handling service. One specific change was a focus on early resolution. Early resolution involves assessing which complaints can be considered quickly and an outcome reached without the need for further in-depth investigation. Common early resolution strategies include transferring a complaint back to the agency to consider or asking simple preliminary inquiries of an agency to determine answers without the need for a full investigation.

There are a number of outcomes that can result from contacting us. When a complaint about a government agency is received, the most common action we take is to advise the complainant to contact the agency that the complaint is about. We do this because in most circumstances, the most efficient way to resolve a complaint is for the agency to consider and resolve it. Other common actions are to provide the complainant with other advice to resolve their matter or to assist vulnerable or at-risk people by directly transferring their complaint to the agency concerned to consider it further.

While many complaints can be effectively assessed, and a way forward determined, without the need to contact the agency concerned, others require more in-depth investigation to determine the appropriate outcome. We may also investigate a matter even where it is not likely to lead to a better result for the individual concerned, to ensure we provide effective oversight of agencies and influence systemic improvement in public administration.

Often we will decide that we need to engage with the agency complained about to determine what happened. There are two ways we do this—by making a simple enquiry with the agency (533 complaints in 2018–19) through to commencing a more detailed investigation (1,116 complaints in 2018–19).

CASE STUDY

A complainant complained to our Office that the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) had deregistered their company because they had not paid the annual review fees. They told us that even though they had advised ASIC of a change to the address for their company, the annual company review fee invoices were sent to the old address and as a result, they had not paid the annual fee. Once they became aware of the error, they paid the annual review fee. They complained it was not fair to have to pay fees for late payment of the annual review fee.

We conducted preliminary inquiries and asked ASIC for information on how it processed the request to change the company address. After receiving our preliminary inquiry, ASIC realised it had not properly processed the change of address for the company. It reassessed its handling of the matter and agreed to reinstate the company's registration and waive the fees relating to the late payment of the annual company review fee.

Investigating complaints

Investigating complaints remains a core component of the Office's function of providing oversight and assurance of government administrative action and complaint-handling. As a result of an investigation, we may make comments or suggestions to the agency. Comments or suggestions may include recommendations to change or review decisions, policy or procedural changes encouraging formal apologies to complainants and improving the quality of publicly available information.

In 2018–19 we investigated 1,116 complaints, and provided comments or suggestions to the agency in 84 cases. This does not include those cases where the agency agreed to make changes during the course of our investigation.

Outcomes

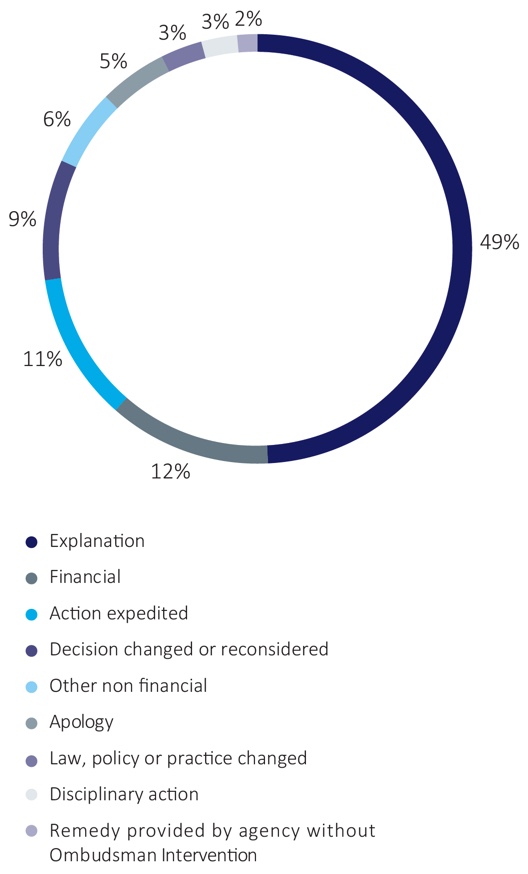

Regardless of what action we take, contact with our Office can result in a variety of outcomes including a better explanation of a decision or process, faster resolution of a matter, reconsideration of a decision and sometimes a financial remedy (for example, waiver of a debt or reinstatement of a payment to which the complainant is entitled).

In other cases, our investigation can result in independent assurance that an agency acted appropriately and made the right decision. While this is not always the outcome a person is seeking in coming to our Office, it highlights that our role is to be independent and impartial—we do not advocate for either individuals or agencies.

Figure 4 sets out the different types of outcomes following investigation of cases. Further work is underway this year to enable reporting on the outcomes we achieve without a formal investigation.

Figure 4—Investigation outcomes

Reviewing our decisions

The Office has a formal non-statutory review process for complainants who may be dissatisfied with the decision reached by the Office about a complaint. Generally, the officer who made the decision is expected to contact the complainant to discuss their concerns and if needed, consider new information or explain the decision in more detail. If the complainant is still unhappy after this contact, they can seek an internal review.

A review manager decides whether to grant a review. A review may not be granted if the review manager cannot identify any concerns with the original officer's decision. If a review is granted, the review manager allocates the review to an experienced officer who was not previously involved in the matter.

In 2018–19 we received 146 requests for review (representing 0.8 per cent of complaints finalised), compared to 155 (0.78 per cent of finalised complaints) received in 2017–18.

The review manager accepted 78 requests for further review. Review officers affirmed the original decision in 62 cases and decided to investigate the matter further in 19 cases.

Reviews are an important part of the Office's commitment to best practice complaint-handling. The Office reports internally to the executive on the issues identified in reviews and uses reviews as an opportunity to continually improve our own practices and procedures.

Accessibility of our services

The Office is committed to ensuring that our services are accessible to all people. It is particularly important that our complaint-handling processes are available in a way that all people can readily access them. In 2018–19 we undertook the following to support that commitment.

Multicultural Access and Equity Plan (MAEP)

In early 2019, the Office launched our 2019–20 Multicultural Access and Equity Plan. The plan outlines our commitment to ensuring that our services meet the needs of all Australians, regardless of their cultural and linguistic background. Through this plan, we outline practical commitments to ensure that multicultural access and equity consideration are embedded in our organisational culture.

The commitments in the plan cover Leadership, Engagement, Responsiveness, Performance, Capability and Openness. These commitments are essential to our vision of creating a service that is equitable so that all Australians are safeguarded in their dealings with Australian Government agencies and prescribed private sector organisations.

Disability accessibility

During 2018–19, we continued to implement recommendations arising from our Office's review of its disability accessibility by specialist disability consultants, WestWood Spice and Partners. We launched our new website, featuring improved layouts and content focussed on ease of use for people wanting to contact our Office. We also rolled out Disability confident managing and recruiting training for our staff, which ensures that recruitment and selection teams are disability aware and confident and that managers are better able to supervise staff with disability.

Indigenous accessibility

A review of the Office's accessibility and inclusiveness of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities was conducted by the Aboriginal communications company Gilimbaa Pty Ltd in 2017. The review considered all aspects of the Office's operations and made recommendations to improve our approach to engaging with Indigenous complainants and stakeholders. During 2018–19, we implemented recommendations promoting and supporting the importance of effective communication with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander audiences, which involved identifying Indigenous champions in our public contact areas, and working across the Office to ensure that complaint-handling practices are culturally appropriate.

We delivered training to staff in how to use Indigenous Language Interpreters to communicate and engage with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities. We also refined our intake processes to improve the identification of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander complainants, enhancing our ability to collect information about the locations, volume and type of complaints from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This information directly improves our services and assists us in identifying current and emerging systemic issues.

Outreach and community and stakeholder engagement

The Office conducts outreach and stakeholder engagement activities to raise awareness of the role of the Ombudsman's Office and to gather information about systemic issues with government service delivery.

Our outreach activities involve holding round table meetings and visiting community organisations to discuss systemic issues with government service delivery. In 2018–19, we conducted outreach in western Sydney, Logan in Brisbane, southern Perth and north-east Alice Springs.

Our stakeholder engagement involves participating in community forums and networks and engaging directly with non-government organisations that represent people accessing government services.

Complaint assurance initiatives

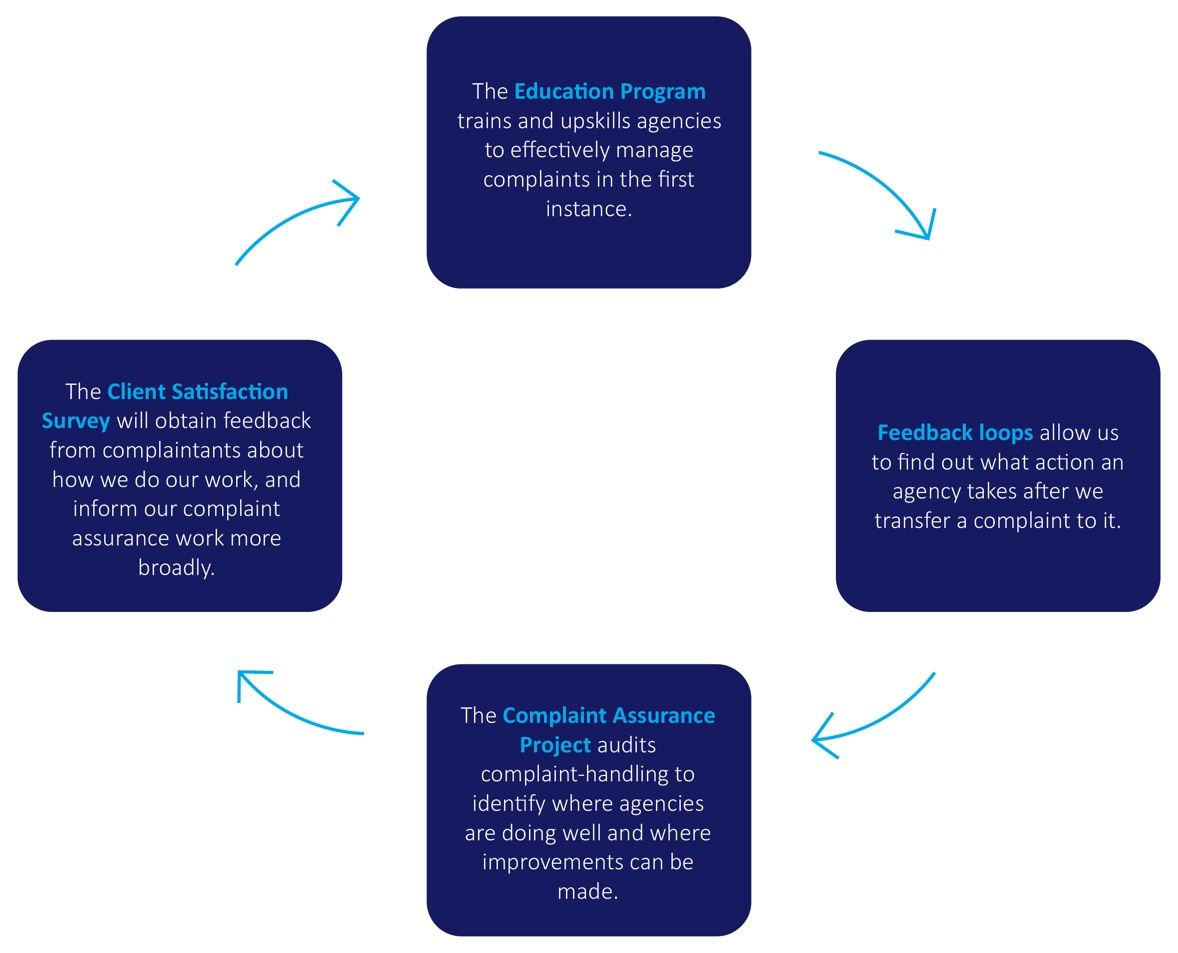

A strong complaint-handling system is an integral part of an agency's performance management and measurement of customer satisfaction. Well-managed complaints can:

- improve trust with people and the perceived integrity of agencies

- lead to better services for people

- identify systemic issues or areas for improvement within agencies.

We often refer the complainant back to the agency about which they are complaining, in order to have their complaints handled by the agency. Starting in 2018–19 and continuing in 2019–20, we have commenced a number of initiatives to assist us to gain assurance that complainants will have their complaints handled appropriately if they are referred back.

We have established an education program, to enable us to share our complaint-handling experience with agency staff. We have trialled a Complaint Assurance Project, to examine complaint-handling policies and practices within agencies to identify best practice and opportunities for improvement. We are rolling out feedback loops for some select complaints we transfer back to agencies, to provide us with assurance that the agency has properly addressed the matter. Finally, in 2019–20 we will be undertaking a satisfaction survey, to critically assess both our own complaint-handling performance and to better understand the experience of those complainants we referred back to the agency.

Amie Meers, Tina Meimaris and Charles Turner visiting the Ampilatwatja Centrelink agent access point, north east of Alice Springs.

Figure 5—Complaint assurance initiatives

Education program

In 2018–19 we initiated an education program targeted at improving complaint-handling by public sector agencies. We developed the program as a way of proactively educating agencies on best practice complaint-handling. Our vision is that with a robust agency-focused education program, we will assist agencies to manage complaints effectively and efficiently while using complaints as a valuable tool to improve their service delivery. This program builds on the Commonwealth Complaint-Handling Forum, which we have successfully held for many years to bring together complaint-handling staff from across Australia.

In May 2019, we introduced a one day interactive complaint-handling workshop based on our Office's Better Practice Guide to Complaint-Handling. The workshop examines the essential elements of an effective complaint-handling system and invites participants to think critically about their agency's complaint-handling processes. The workshop is targeted at frontline complaint-handling staff and their supervisors.

Complaint Assurance Project

The Office is piloting has started a Complaint Assurance Project to review participating agencies' complaint management services in line with the requirements of the Office's Better Practice Complaint-Handling Guide.7 This involves working collaboratively with participating agencies to engage in a self-assessment and oversight process to:

- promote agency-led quality assurance in complaints management

- establish a model for agencies to self-identify trends, systemic issues and areas for improvement

- assist agencies to identify and improve complaint management

- recognise accomplishments and better practice improvements within agency complaint management

- share areas of potential business process improvements with other agencies.

The project involves the completion of a self-assessment questionnaire by the agency and a review of supporting documentation and complaint sampling by our Office.

At the end of the process, our Office will develop a report that identifies best practice and recommendations for improvement. If the pilot is successful, a rolling program involving other agencies will be developed.

On 14 June 2019, the Office hosted the seventh Commonwealth Complaint-Handling Forum at the National Museum of Australia. This year's theme, 'Complaint-handling in the modern world', led to thought provoking presentations and workshops as we explored the current and emerging challenges in complaint-handling. This year's forum was led by joint keynote presentations by Megan Hunter from the High Conflict Institute and David Locke, CEO and Chief Ombudsman of the Australian Financial Complaints Authority.

Workshops by the National Office for Child Safety, the Department of Human Services–Child Support, the Fair Work Ombudsman and the Commonwealth Ombudsman, along with a panel discussion by industry complaint-handling organisations, rounded out another stimulating forum.

Feedback was overwhelmingly positive, with many suggestions to help make the 2020 event another success!

Oversight of government agencies

We work with government agencies to influence enduring systemic improvement in public administration. We do this by monitoring our complaints data, investigating systemic issues and meeting with agencies on a regular basis to explore issues and receive briefings on program or service delivery changes.

For example, in 2018–19 we worked with the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PMC) to monitor the administration of penalties applied to remote job seekers in the Community Development Programme (CDP). Our complaint investigations identified issues associated with the flow of information across the program, participant activity plans and barriers experienced by participants in attempting to access employment services assessment processes.

On 21 September 2018 the acting Ombudsman appeared before the Senate Standing Committee on Community Affairs inquiry into the Social Security Legislation Amendment (Community Development Program) Bill 2018. The bill sought to extend the targeted compliance framework that currently applies to jobseekers to CDP participants, and the Office provided information about issues identified through complaints and from outreach to remote communities.

We also worked with the Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business to monitor complaints about the jobactive program, which represents 80 per cent of complaints about the department. Jobactive program participants are encouraged to make a complaint to their provider in the first instance. Where they are not satisfied with the outcome of their complaint, jobactive participants can access the department's National Customer Service Line (NCSL) either by phone or email. The Department also has a complaint form available on its website.

CASE STUDY

A complainant was a participant in the jobactive program and was referred to a position as a labourer by an employment service provider. They found out they were being underpaid, and their provider referred them to the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) who advised they had a right to leave the position and assisted them in doing so.

The complainant told their provider they had left, but the provider lodged a non-compliance report to Centrelink, resulting in their Newstart Allowance being suspended. When they complained to the National Customer Service Line (NCSL), they were told to contact the Fair Work Ombudsman.

They then made a complaint to our Office. Our investigation identified errors on the part of the provider and found that on the basis of the information that was provided in the complaint to the NCSL, it would have been appropriate for the NCSL to refer the complaint to the provider for further investigation. The complainant's payment was restored, with back pay, and their record corrected.

Department of Human Services

The Department of Human Services (DHS) is responsible for delivering a range of social welfare, health, child support and other payments and services to millions of people across Australia. This includes Centrelink payments and services for retirees, the unemployed, families, carers and students, as well as aged care payments to services that are funded under the Aged Care Act 1997, and Child Support services.

Complaints overview

In 2018–19 we received 11,652 complaints and finalised 11,702. This is a 7.5 per cent decrease in complaints received, compared to 2017–18.

| DHS programs | 2018–19 |

|---|---|

| Centrelink | 10,300 |

| Child Support | 1,100 |

| Department of Human Services | 252 |

| 11,652 |

Centrelink program complaints

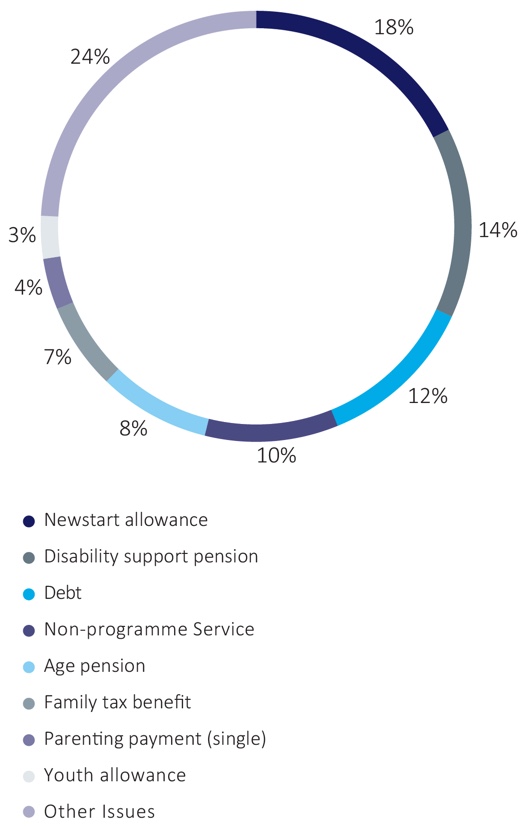

Complaints about Centrelink continue to make up a substantial proportion of complaints made to the Office, representing 55 per cent of the total number of complaints made about Commonwealth Government agencies. Approximately 31 per cent of issues raised in Centrelink complaints are about Disability Support Pension (DSP) and Newstart Allowance (NSA). Figure 6 shows the main issues raised about Centrelink.

CASE STUDY

In 2013, Centrelink granted a claim for a complainant for the Age Pension. In 2017, the person's financial advisers identified that they were incorrectly receiving a reduced rate of Age Pension because Centrelink believed they were a homeowner.

The complainant sought compensation from Centrelink under the Compensation for Detriment caused by Defective Administration (CDDA) Scheme on the basis that their claim had been incorrectly assessed and they had been underpaid for four years. Centrelink assessed the CDDA claim and decided that compensation was not payable.

They made a complaint to our Office. Following our investigation, Centrelink offered compensation in the form of an amount in excess of $25,000, equal to the additional Age Pension that they should have been paid over the four year period.

Figure 6—Centrelink complaint issues

Investigations

In April 2019, the Office published a report on the implementation of recommendations arising from our 2017 report into Centrelink's automated debt raising and recovery system. We found that DHS had made significant progress in implementing our recommendations, but thought some further action was required so made four additional recommendations to improve transparency and fairness. We continue to investigate complaints about this issue.

Feedback loop

We have been working with DHS to establish a feedback loop for complaints that we transfer directly to DHS. We do this where a person has not complained to DHS in the first instance and we think the person is particularly vulnerable and/or will need help with their concerns. DHS provides a quarterly report on all complaints we transfer to the department. The report includes information about whether the person received the outcome they were seeking, and the time it took DHS to contact the person and to resolve the complaint. DHS also provides more detailed information on a sample of complaints each quarter, so we can see the steps DHS took to respond to the complaint.

Child Support Program

Our Office has jurisdiction to investigate complaints about DHS' administration of the Child Support program. This includes child support assessments, registering child support agreements, and collecting and disbursing child support between separated parents and the carers of eligible children.

In 2018–19 the number of complaints received about Child Support decreased by 16.3 per cent. The majority of complaints received in 2018–19 were from paying parents. The main complaint themes were regarding the collection and enforcement of child support liabilities, formula assessments, change of assessments and customer service.

In addition to investigating individual complaints, the Office liaised with DHS on a range of Child Support matters, including the Parent Support Team pilot for vulnerable clients, debt recovery processes, and the continued rollout and implementation of a new information technology system.

National Disability Insurance Agency

The National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) administers the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), a Commonwealth scheme that provides funding to people with disability to assist them to participate in everyday activities. People who enter the NDIS are known as participants.

The NDIS is being introduced across Australia. At 30 June 2019, 298,816 participants had received approved plans (or were in the Early Childhood Early Intervention gateway). Approximately 460,000 participants are projected to be in the scheme by July 2020. How and when people with disability are able to access the NDIS depends on the state or territory in which they live and whether they have accessed disability services before. As at 30 June 2019, people across most of Australia can access the NDIS, with the roll out of the scheme in Western Australia due for completion by June 2020.

The Office handles complaints about the NDIA's administrative actions and decisions. We can also consider complaints about organisations that are contracted to deliver services on behalf of the NDIA, including local area coordinators who conduct information gathering and pre-planning interviews and Early Childhood Early Intervention partners.

Complaints overview

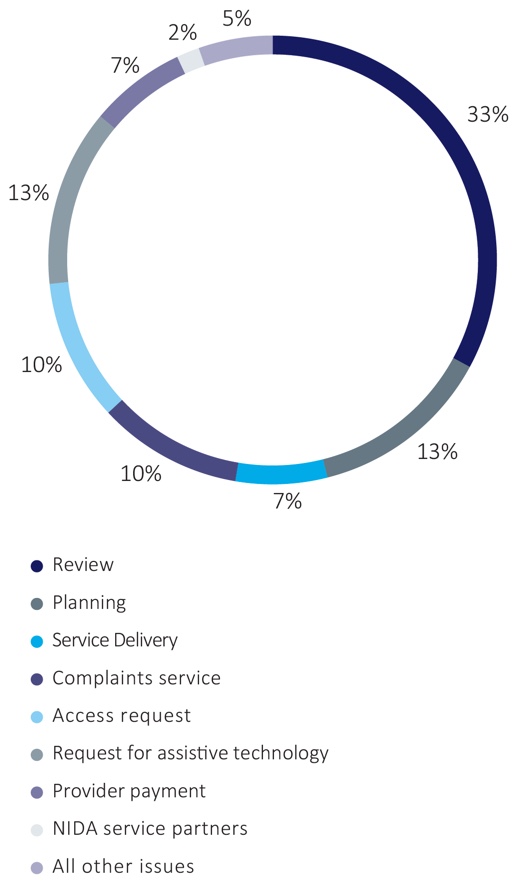

In 2018–19 we received 1,711 complaints and finalised 1,764. This is a 12 per cent increase in complaints received compared to 2017–18. During the same period the number of NDIS participants increased by 62 per cent.

Figure 7—NDIA complaints received

Complaints to our Office in 2018–19 covered many aspects of participants' experiences with the NDIS, as well as providers' experiences. The most common complaint issue was the NDIA's handling of reviews of plans and decisions.

Other common complaint issues included:

- Difficulty and delays in navigating the assistive technology process, and having funding for assistive technology included in plans for things like home and vehicle modifications.

- Dissatisfaction with the NDIA's handling of complaints made to its complaints service.

- Delays in deciding requests for access to the NDIS and confusion about timeframes for receiving an NDIS plan after access to the scheme is granted.

- Dissatisfaction with the process and outcome of planning meetings.

A breakdown of complaint issues is provided in Figure 8.

Figure 8—NDIA complaint issues 2018–19

CASE STUDY

A complainant requested a review of the NDIA's decision to decline the request for specialist funding for a wheelchair (in their child's plan). The NDIA undertook the review and confirmed its original decision. Although the NDIA verbally told the complainant the decision, it did not send them or their child a written decision. Without a written decision, they were unable to seek merits review of the NDIA's decision by the Administrative Appeals Tribunal (AAT).

They complained to our Office. We contacted the NDIA and it sent a decision letter to their child. They were then able to exercise their rights to review the NDIA's decision.

Handling of reviews

In 2018–19, complaints about reviews including delays and decisions continued to feature prominently in complaints to the Office about the NDIA.

We are continuing to follow up the NDIA's implementation of the recommendations made in our public report, Administration of reviews under the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013. The report made 20 recommendations aimed at improving review processes, communication with participants and review timeframes.

Accessing assistive technology

Complaints about the NDIA's administration of assistive technology increased this year to 12.6 per cent of all NDIA complaints to the Office, compared with five per cent of NDIA complaints last year.

Many of the complaints highlight difficulties experienced by participants in having funding for assistive technology included in their NDIS plan and in obtaining clear and timely responses from the NDIA about what is needed to support the assistive technology request.

In late 2018, the Ombudsman made a submission to and appeared before the Joint Standing Committee on the NDIS's inquiry into the provision of assistive technology. Our submission highlighted the issues raised in complaints to the Office including:

- delays in making decisions

- an apparent lack of clear guidance about how to make a request and what information or evidence is required

- inconsistencies in advice about who can prepare assistive technology quotes and what they need to include.

CASE STUDY

A person contacted our Office due to delays in receiving assistive technology in their NDIS plan. They told us they were in hospital and were waiting for the NDIA to approve funds so they could obtain customised mobility equipment, and have modifications made to their home. Once the modifications were made they could leave hospital and go home. They told us that they had followed all the steps including providing quotes and assessments, and despite calling the NDIA multiple times had waited five months for a decision before approaching our Office.

We investigated their complaint. We noted that the request had been handled by multiple teams and there had been lengthy delays in both processing the request and responding to the participant's attempts in following up the NDIA's decision.

During the investigation, the NDIA acknowledged the complexity of this participant's circumstances. It took action to provide a support coordinator to assist the participant in engaging with the hospital and in obtaining the mobility equipment and the required modifications, so the participant could leave hospital and return home.

Defence Force Ombudsman

Our role as the Defence Force Ombudsman involves two main functions. We provide an independent complaints mechanism for serving and former members of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). Since 2016, we have received reports of serious abuse from serving and former members of Defence who feel they are unable to access Defence's internal mechanisms.

Complaints function

As the Defence Force Ombudsman, we receive and investigate complaints about administrative action taken by Defence agencies, including the the three services (Navy, Army and Air Force), the Department of Defence (Defence), the Department of Veterans' Affairs (DVA) and Defence Housing Australia.

Defence complaints overview

In 2018–19 we received 471 complaints about Defence agencies and finalised 491. This is a 27.9 per cent decrease in comparison to complaints received in 2017–18. Complaints about Defence agencies, raised concerns about issues such as:

- termination, separation and transition

- service delivery

- redress of grievance

- Defence force recruiting.

Investigations

In July 2018, the Ombudsman published a report on our Investigation into the Actions and Decisions of the Department of Veterans' Affairs into the handling of a complex case involving compensation and disability benefits. The report made a number of recommendations to improve DVA's administration of veterans' payments. The department worked collaboratively with the Office and accepted all our recommendations. DVA has advised it is implementing significant systemic changes, as part of its transformation agenda, to improve the way it manages and interacts with veterans and their families. The Office will continue to monitor DVA's ongoing work to implement our recommendations.

Defence Force Retirement and Death Benefits Scheme—own motion investigation

On 5 April 2019, the Ombudsman commenced an own motion investigation into the administration of the Defence Force Retirement and Death Benefits (DFRDB) scheme, specifically the issue of commutation.

The investigation is focused on accuracy of information about commutation provided to scheme members by the Department of Defence, ADF and scheme administrators (including the Commonwealth Superannuation Corporation (CSC) and its predecessors).

Given the significant public interest in this matter, we invited public submissions and received 3417 submissions from scheme members. We have also requested and obtained relevant records from Defence and CSC, going back more than 40 years.

We intend to finalise our investigation before the end of 2019. We will publish updates on the progress of the investigation here: ombudsman.gov.au/dfrdb

Abuse reporting function

Since 1 December 2016, the Ombudsman has been able to receive reports of contemporary and historical abuse within Defence. This provides an independent and confidential mechanism to report abuse for those who feel unable to access Defence's internal mechanisms.

Abuse means sexual abuse, serious physical abuse or serious bullying or harassment which occurred between two (or more) people who were employed in Defence at the time.

Our delivery of the abuse reporting program is based around three functions:

- We provide a supportive, trauma-informed liaison role to those who report abuse to the Office.

- We assess all reports of abuse to determine whether they are within our jurisdiction and, if requested by the reportee, whether they meet the government's reparation payment framework.

- We deliver available responses including a recommendation for a reparation payment where available, participation in the Office's Restorative Engagement Program, or a facilitated referral for counselling.

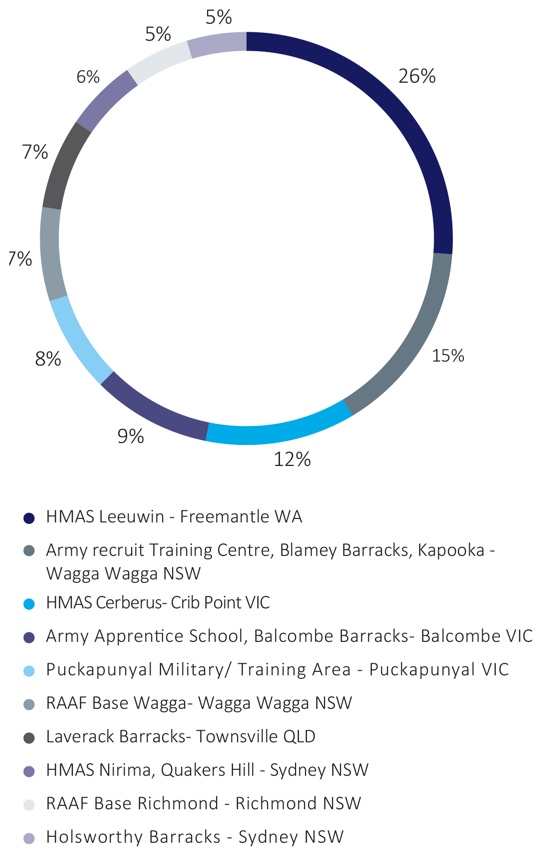

In 2018–19, we received 482 reports of abuse compared to 457 in 2017–18. Of the matters assessed in 2018–19, we accepted 542 reports to be in jurisdiction.

Figure 9—Reports of abuse received

Of the total 542 reports assessed in jurisdiction, the most reported locations were:

Figure 10—Most reported locations

Every person reporting abuse is assigned a dedicated Liaison Officer, who is practiced in communication skills that ensure clear, accurate and empathic messaging and understanding that an experience of trauma can affect a person's ability to engage in processes that may be beneficial. Liaison Officers work closely with reportees to establish rapport and encourage trust.

All reports are thoroughly assessed and the Ombudsman's delegate decides if the report involves serious abuse which is reasonably likely to have occurred in connection with the person's service in Defence. If a report is not accepted, reportees may seek an internal review of our decision.

Most reports of abuse made to our Office relate to conduct and behaviour that occurred many years ago. Of the total 1,101 reports received, only five per cent of reports relate to abuse alleged to have occurred after 30 June 2014.

We receive a range of feedback from current and former Defence members about the processes and outcomes of making a report of abuse to our Office. While many people tell us that it was a positive experience, and in some cases life changing, for some people the process has been challenging and disappointing when the outcome is not what they expected. We value feedback and use it to inform and improve how we manage reports, the information we provide and the assessments we make.

Reparation Payments

On 15 December 2017, the Australian Government determined that for the most serious forms of abuse and/or sexual assault, the Ombudsman may recommend Defence make a reparation payment.

There are two possible payments which we may recommend:

- A payment of up to $45,000 to acknowledge the most serious forms of abuse.

- A payment of up to $20,000 to acknowledge other abuse involving unlawful interference, accompanied by some element of indecency.

If the Office recommends one of these payments, an additional payment of $5,000 may also be recommended where the Ombudsman is satisfied that Defence did not respond appropriately to the report of abuse. As reparation payments are limited, not all reports of abuse will meet the parameters set out in the framework.

Since the announcement of the reparation framework, the Ombudsman's delegate has sent 370 reparation payment recommendations to Defence. As at 30 June 2019, Defence had considered and accepted 327 recommendations.

Restorative Engagement Program

The Restorative Engagement Program is designed to support a reportee to tell their personal story of abuse to a senior representative from Defence in a private, facilitated meeting called a Restorative Engagement Conference. The conference provides the opportunity for Defence to acknowledge and respond to an individual's personal account of abuse.

A secondary objective of the program is to enable a broader level of insight into the impact of abuse and its implications for Defence, which is critical to informing and building cultural change strategies.

Participation in the program is a choice made by the reportees. We explain the objectives of the program to help them make a choice about whether or not to participate.

In 2018–19, a total of 16 Restorative Engagement Conferences were convened with reportees, independent facilitators and Defence representatives. We received feedback via a survey from eight reportees who participated in a conference.

Overall, feedback was positive in terms of the personal benefits such as being able to 'leave bad memories behind' and getting an apology from Defence. Reportees also agreed or strongly agreed they were consulted about the process and had input, felt safe and were supported by the facilitator. Reportees agreed they were able to say what they wanted to say, including about the impacts of the abuse, and they were respected, listened to and believed by the Defence representative.

All reportees who completed the survey agreed or strongly agreed that their relationship, reputation and identity with Defence was repaired or reconciled through the Restorative Engagement Conference.

Defence Health Check

In 2017, the Office established the Defence Health Check as part of our Defence abuse reporting function. The Health Check is a rolling investigation which considers Defence's internal policies and procedures for making and handling complaints about abuse and unacceptable behaviour. In 2018, the Office investigated the adequacy of Defence's written policies for making and responding to reports of abuse. The Ombudsman made six recommendations to Defence to improve consistency and accessibility of the relevant policies.

As part of the Health Check the Office has also completed a review of our Defence abuse reporting function.

We anticipate releasing both reports in the second half of 2019.

The next stage of the Health Check will review the training Defence provides to new recruits in relation to unacceptable behaviour across the three services.

Immigration Ombudsman

The Office investigates complaints about the migration and border protection functions of the Department of Home Affairs and its operational arm, the Australian Border Force (ABF). In addition to dealing with complaints regarding immigration matters, the Office also inspects immigration detention facilities in Australia and elements of offshore processing centres that are within our jurisdiction.

Under the Migration Act 1958 (Migration Act), the Office also has a statutory role to provide the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs an assessment of the appropriateness of a person's detention when that person has been in immigration detention for two years and every six months thereafter.

Complaints overview

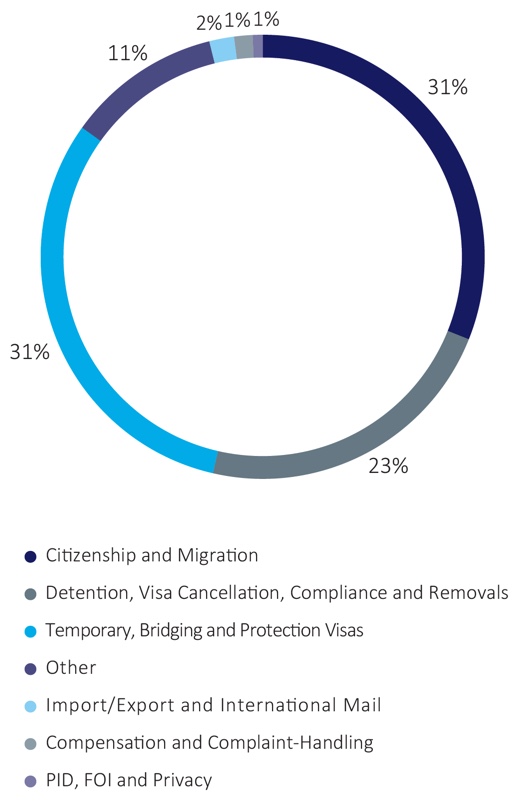

In 2018–19, we received 1,824 complaints about the department, compared with 1,838 complaints in 2017–18.

Complaints concerning Temporary, Bridging and Protection Visas made up the largest category of complaints, followed by Citizenship and Migration, and Detention, Visa Cancellation, Compliance and Removals.

Figure 11—Complaints overview

CASE STUDY

On 22 January 2018, the Department of Home Affairs introduced a new visitor management policy which changed the conditions of entry and entry application process for personal and professional visitors to immigration detention facilities.

The Office monitored the implementation of the policy through our complaints, our inspections of immigration detention facilities and our engagement with stakeholders. In October 2018 we provided an issues paper to the department, outlining our concerns about the policy and making 13 recommendations.

We recommended that the ABF clarify elements of the policy on its website, the application information sheet and the Visiting Multiple Detainees request form; clarify which visitor application process applies to volunteer and community groups and which applies to individuals; and explain how the policy changes would affect these groups on both its website and the Visiting Multiple Detainees request form. The department accepted ten of our recommendations.

In April 2019, the department advised us that the ABF website has been updated to clarify and differentiate the process applying to volunteer and community groups and the process applying to individual visitors. The Office has not received any further complaints raising issues about the introduction of the policy.

Own motion investigations

In December 2018 the Office released an own motion investigation report, Preventing the immigration detention of Australian citizens—Investigation into the Department of Home Affairs' implementation of the Thom Review.8 The investigation looked into the department's implementation of recommendations from the Independent review of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection into the circumstances of the detention of two Australian citizens by Dr Vivienne Thom AM9 at a selection of critical points across the immigration detention process. This identified gaps, where the department's implementation activities had not entirely met its intent or the intent of the relevant recommendations.

Our report made 15 recommendations to the department to address these gaps. The department accepted the Ombudsman's recommendations, 14 in full and one in part. The Office is following up on the implementation of these recommendations.

People detained and later released as 'not unlawful'

The department provides the Office with six-monthly reports on people who were detained and later released as not-unlawful because the department identified the person was an Australian citizen or held a valid visa at the time of detention. Our analysis of these reports indicates that defective notifications continue to be the main cause of inappropriate detention of lawful non-citizens, accounting for 31 of the 44 cases in 2018.

CASE STUDY

A complainant approached our Office as they had recently applied to Centrelink for childcare subsidies and was advised that before their application could be approved, they needed the Department of Home Affairs to update their travel record. The complainant had travelled overseas with their parents when they were a child but their return to Australia was not recorded by the department. The complainant contacted the department, provided exit and re-entry dates and requested that their record be updated.

After some time, they raised a formal complaint with the department about the delay in updating their travel record. As the complainant could not access the subsidy from Centrelink, they were in debt with the childcare centre and their child was no longer able to attend. A response was received from the department which advised the record could not be updated because there was no record of their return to Australia.

The complainant contacted our Office. The Office considered that there was more the department could do to assist and transferred the complaint to the department. On the same day it received the transferred complaint, the department located and corrected the travel record and advised both the complainant and Centrelink of the correction.

Statutory Reporting under s 486O of the Migration Act

Section 486N of the Migration Act requires the Secretary of the Department of Home Affairs to provide the Ombudsman a report on the detention circumstances of any person who has been in immigration detention for two years, and every six months thereafter. This report includes details of the person's case progression, detention history, medical treatment, family information and any relevant criminal or security concerns.

Under s 486O the Office makes an assessment of the detention circumstances of each person, and provides this assessment to the Minister for Immigration, Citizenship, Migrant Services and Multicultural Affairs. The assessment may include recommendations the Ombudsman considers appropriate. The Minister tables a de-identified copy in Parliament, which includes a response to any recommendations.

In 2018–19 we received 1,069 s 486N reports from the department. We sent 722 s 486O assessments to the Minister, including 248 recommendations, which were based on 1,034 reports from the department. The recommendations relate to the following issues that have been evidenced through the detention reports this year:

- There is a cohort of people who are in long term detention, either in the community or a detention facility, for whom there is no apparent resolution to their case. These include people who for various reasons cannot be removed from Australia, but who remain in detention as they have been assessed as not passing the character test imposed by the Migration Act. While we recognise the constraints such circumstances place on the Minister and the department, we continue to make recommendations for an outcome for these individuals.

- There is a small number of Irregular Maritime Arrivals (IMAs) who have received an adverse or qualified security assessment (QSA) and continue to be held in immigration detention. Unlike holders of an adverse assessment, detainees with a QSA may be released from an immigration detention facility, either to a community placement or on a bridging visa and we continue to make recommendations for consideration of whether these detainees could be released from an immigration facility either into community detention or on a bridging visa.

- A number of asylum seekers who arrived in Australia by sea after 19 July 2013 and transferred to a Regional Processing Country (RPC) have been returned to Australia to receive medical treatment. Under current policy settings these people remain liable to be returned to an RPC when their medical treatment has concluded. We continue to make recommendations that the department explore options to address this cohort's prolonged detention.

- The movement and placement of individuals in the detention network that impacts their access to family and support networks and their ability to attend specialist medical or court appointments.

- Delays in case progression, including processing of requests for revocation of visa cancellation decisions.

- Family members on different immigration pathways.

Detention inspections

The Migration Act enables the detention of unlawful non-citizens, such as those who enter or remain in Australia without a valid visa. Detention has been mandatory for all unauthorised maritime arrivals since 199410 and for people whose visas have been cancelled on character grounds since 2014.11

While placement in an immigration detention facility is mandatory for certain cohorts, it is administrative in nature—an individual is detained for the purpose of conducting an administrative function.

Currently the operations of the immigration detention network are not supported by a legislative framework. The reliance on an administrative rather than a legislative framework to underpin the operations of the network remains a concern for our Office.

The Office undertakes oversight of immigration detention facilities. The inspection function has been undertaken under the provisions of the Ombudsman's own motion powers.12

During 2018–19 we inspected the immigration detention facilities listed in Table 2.

| Immigration Detention or Regional Processing Facility | Location | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| Adelaide Immigration Transit Accommodation | Adelaide SA | September 2018 April 2019 |

| Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation | Brisbane QLD | September 2018 June 2019 |

| Manus Island | Papua New Guinea | July 2018 |

| Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation | Melbourne VIC | December 2018 March 2019 |

| Nauru Regional Processing Centre | Nauru | December 2018 |

| Christmas Island Immigration Detention Centre | Christmas Island Indian Ocean Territories | August 2018 |

| Perth Immigration Detention Centre | Perth WA | October 2018 May 2019 |

| Villawood Immigration Detention Centre | Sydney NSW | October 2018 April 2019 |

| Yongah Hill Immigration Detention Centre | Northam WA | October 2018 April 2019 |

| Transfer Operations | Sydney-Melbourne-Perth-Christmas Island-Perth-Melbourne Melbourne-Sydney-Brisbane-Perth-Melbourne | August 2018 March 2019 |

During these inspections we examine the administrative and operational practices and procedures of the centres. The Office provides feedback to the facility after each visit, including any observations and suggestions. The Office submits a formal report to the department at the end of each inspection cycle (every six months) to summarise our inspection activities and observations.

The issues that arose over this reporting period include:

- placement of detainees in the detention network

- security risk rating assessment

- use of certain restrictive practices in detention

- use of security-based models within administrative detention

- internal complaint management

- facilities available within the new high security compounds

- introduction of the high security vehicles

- management of non-medical Alternative Places of Detention (APOD)

Assessments of the services provided to asylum seekers undergoing regional processing on Nauru and/or Papua New Guinea is limited to those functions directly contracted by the Australian Government and provided onsite to asylum seekers and refugees. This assessment does not consider the actions or the services provided by the respective host nations.

Placement of detainees in the detention network

The Australian Government, through the Australian Border Force (ABF) and its respective facility Superintendents, has a duty of care to all detainees.13 The Office continues to be concerned about the number of detainees who are placed in facilities which are in a different state to their families or support networks. We acknowledge that operational needs, such as the shortage of beds in a number of east coast centres and security risk ratings, will have an impact on placement decisions. We have noted improvements in placement decisions, with greater weighting being placed on family, medical and legal considerations.

We encourage the ABF to continue to take all relevant information into account when placing detainees in the network, including considering the positive influence on detainees of being placed in locations that maintain strong family engagement, access to legal representatives and support networks.

Security risk assessments

The Office continues to be concerned about the consequences of an inaccurate or a poorly analysed security risk assessment that is applied to a detainee without consideration of individual circumstances. During our inspections we undertook assessments of the security risk assessment processes in each facility and noted ongoing issues with the algorithm that underpins the security risk assessment tool. The algorithms appear to be rigid in their application and make linkages between behaviours and outcomes that are not supported by the evidence available to the analyst.

The ABF had scheduled a review of its security risk assessment process including the assessment tool for this reporting period, but this did not eventuate.

Restrictive practices in detention

The department and their service providers have a duty of care to both detainees and staff to protect them from violent or aggressive behaviours and damage to people or property. We acknowledge that there are occasions where, for the good order, security and welfare of the facility, a detainee may need to be placed in restraints or moved to a low stimulus environment (High Care Accommodation). However we have noted the following concerns.

Use of restraints

We acknowledge mechanical restraints may be required for detainees who pose an unacceptable flight risk or are of such a violent disposition that there is no other option to address the risk of injury to themselves or others and/or damage to property. We remain concerned that the use of mechanical restraints is the first rather than last choice to address these risks, especially during:

- long haul air transfers where detainees are mechanically restrained with two escorting officers for the duration of the flight

- attendance at medical or other appointments where we have been advised by detainees that they have declined to attend medical appointments as being handcuffed and walked through a hospital or other public area is demeaning and embarrassing.

Security-based model of administrative detention

We acknowledge that the number of detainees currently in immigration detention with histories of violent or anti-social behaviours requires an increased focus on safety and security. During 2018–19 we noted the continued use of 'controlled movement models', with the most restrictive of all operational models being the preferred operating model for the majority of the network. This was particularly evident in facilities where high security compounds were newly commissioned and the detainee population had increased with the transfer of detainees from high security facilities to facilities that had once been a low/medium security facility.

In this model, detainees are restricted to specific compounds and are unable to move freely within the centre. We acknowledge there are circumstances where this model is appropriate, such as in facilities where detainees are vulnerable to coercion or intimidation immediately following periods of unrest or where the detainees' ongoing behaviours warrant a high level of protective security. However, this model should not be the first preference for an administrative detention environment.

We remain concerned that security is consistently outweighing welfare considerations in operational decision making. Both welfare and security considerations are of equal importance and neither should be automatically preferred when operational matters are being decided.

Internal complaint management

The management of internal complaints continued to be one of our primary focuses during the 2018–19 period. Record-keeping and investigative practices remain inconsistent throughout the network. While we noted strong record-keeping and investigative practices in some facilities, we noted a significant deterioration in other facilities. We continued to work with stakeholders during this period to address the shortfalls in record-keeping and complaint resolution practices, including the development of effective complaint management process and internal quality assurance processes.

Facilities

During this reporting period the Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre (IDC) closed and the Christmas Island IDC was placed into contingency mode, then reopened again. Redevelopment of the Melbourne and Brisbane Immigration Transit Accommodation Centres (ITA) and the Yongah Hill IDC were also completed in this period.

The modularised high security compounds at Melbourne ITA and Yongah Hill IDC were commissioned during the latter period of this reporting period. We noted a number of significant shortfalls in the provision of suitable accommodation in these compounds including:

- Mobility access to accommodation units. Most of the new high security compounds do not adequately provide for a mobility impaired detainee and do not appear to meet the required access standards.14 In one of the facilities we observed that the outside areas of the compounds, including recreation space, pose a significant risk of trips or falls for all detainees due to poor drainage and inadequate preparation of the compound prior to occupancy.

- Privacy considerations in reception, rooms and High Care Accommodation.

- Lack of facilities to appropriately distribute medicines.

- Lack of facilities for programs and activities, for example the programs and activities rooms within the compounds had not been fitted out with appropriate equipment and remained empty, the access to seating in the common rooms was poorly designed and there was limited access to individual entertainment.

- The accommodation rooms do not have any capacity for detainees to secure personal property in their possession.

Transport and Escort

During this inspection cycle we observed the introduction of the Serco high security vehicle. This vehicle is based on a custodial services vehicle used to transport convicted criminals between facilities or courts.

During 2018–19 these vehicles were in use without appropriate guidelines or directions in place as to how this vehicle was to be used, under what circumstances and with whose authority.

We acknowledge that the ABF has directed the vehicles be removed from the authorised fleet. We remain of the view that new equipment including vehicles should not be introduced without detailed policy and procedural guidelines being in place.

Alternative Places of Detention (APOD)

An APOD is any place declared to be a place of detention and may include hospital facilities, mental health facilities, and hotel rooms or serviced apartments. APODs are established where it is not appropriate to house a person in an established detention facility and can exist for periods of a few hours to weeks or months.

During 2018–19 we noted an increase in the use of APODs to house family groups with children and other vulnerable detainees including medical transferees and their support from regional processing countries.

We acknowledge that choice and location of an APOD that is not a medical facility is dictated by availability and appropriate cost considerations. However, we have noted that a number of motels used as APODs have limited onsite access to outdoor recreational space, educational, cultural and religious activities. The lack of outdoor space is of particular concern when children are involved.

Where an APOD is established and is likely to be in operation for more than a few days it is reasonable for the detainees to have access to appropriate welfare and engagement services including programs and activities. In a number of locations it was apparent these services had not been provided. In one particular location, service providers were confused as to what level of welfare support should be provided at an APOD, and who should provide it.

Oversight of Law Enforcement

Law Enforcement Ombudsman

Our role as the Law Enforcement Ombudsman involves oversight of the Australian Federal Police (AFP), for which we have three main functions. We assess and investigate complaints about the AFP, receive mandatory notifications from the AFP regarding complaints about serious misconduct involving its members, under the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 (AFP Act), and conduct statutory reviews of the AFP's administration of Part V of the AFP Act.

Complaints overview

In 2018–19 we received 262 complaints and finalised 263 complaints about the AFP.15 This is a 1.6 per cent decrease from complaints received in 2017–18. The issues raised by the public in AFP complaints to our Office concerned:

- inappropriate action, including the failure to investigate complaints or inadequate investigation of complaints

- customer service experiences when making complaints.

Under the AFP Act, the AFP is required to notify our Office about any complaints it receives about serious misconduct matters. The AFP complied with this obligation during 2018–19.

The Office conducted one review of the AFP's administration of Part V of the AFP Act during the year, with the report to be published in 2019–20. We published the 2017–18 annual report under Part V of the AFP Act in May 2019. As part of this year's review, we engaged with the AFP Professional Standards (PRS) team and Safe Place team16 to discuss their management of complaints under Part V of the AFP Act.

CASE STUDY

AFP Safe Place was established to provide support to people who have suffered sexual harassment or bullying and to give them the reassurance that their concerns will be treated with respect, sensitivity and confidentiality. Safe Place is available to former and current AFP members, who are encouraged to bring matters to the team, even if they have already reported previously through existing processes. In 2017–18, we met with representatives from Safe Place to discuss their management of complaints under Part V of the AFP Act.

In 2018–19, we made recommendations to the AFP regarding Safe Place and the handling of complaints. These recommendations included:

- The AFP update its policies and procedures to provide both written and verbal information to complainants to ensure they are provided with consistent information and the integrity of the investigation and decision process can be easily established and reviewed.

- The AFP ensure investigators are aware of appropriate notification practices and procedures.

The AFP undertook to implement our recommendations to improve its policies and procedures in relation to Safe Place. The Office will continue to monitor this program through our reviews under Part V of the AFP Act, regular liaison with the AFP and any complaints we may receive.

Our 2017–18 reviews found the AFP's administration of Part V of the Act to be comprehensive and adequate with matters investigated appropriately. However, we identified some deficiencies in how the AFP responds to practices issues and made several suggestions to improve record-keeping processes, and adherence to legislative requirements and standard operating procedures.

Inspections of covert, intrusive or coercive powers

Oversight activities

In 2018–19, the Office performed oversight functions under various pieces of legislation which grant intrusive and covert powers to certain law enforcement agencies, for example under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979, the Surveillance Devices Act 2004 and Part IAB of the Crimes Act 1914.

We are required to inspect the records of enforcement agencies and report to the Minister17 on agencies' compliance with the above legislation. Reports to the Minister are subsequently tabled in Parliament.

The Office also performed oversight functions in relation to specific coercive information gathering powers18 used by the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO) under the Fair Work Act 2009, and the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) under the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016. Our role is to review and report quarterly to Parliament on the exercise of these powers by the ABCC and FWO.

Overview of our oversight activities in 2018–19

| Power | Legislation | Agencies subject to inspection |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled operations authorities | Crimes Act 1914 – Part IAB | AFP ACLEI ACIC |

| Delayed notification search warrants | Crimes Act 1914 – Part IAAA | AFP |

| Control orders | Crimes Act 1914 – Part IAAB | AFP |

| Industry assistance requests and notices | Telecommunications Act 1997 – Part 15 | All State/Territory police forces, plus: AFP ACIC |

| Telecommunications interceptions | Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 – Chapter 2 | AFP ACLEI ACIC |

| Stored communications | Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 – Chapter 3 | All State/Territory police forces, plus: ACIC ACCC ACLEI AFP ASIC Corruption & Crime Commission (WA) Crime & Corruption Commission (QLD) Home Affairs IBAC (Victoria) Law Enforcement Conduct Commission NSW Crime Commission ICAC (NSW) ICAC (SA) |

| Telecommunications data (metadata) | Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 – Chapter 4 | |

| Surveillance device warrants | Surveillance Devices Act 2004 | All State/Territory police forces, plus: ACIC ACLEI AFP Corruption & Crime Commission (WA) Crime & Corruption Commission (QLD) Law Enforcement Conduct Commission NSW Crime Commission ICAC (NSW) |

| Part V | Part V of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 | AFP |

| Power | Legislation | Agencies subject to inspection |

|---|---|---|

| Exercise of examination powers | Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016 | Australian Building and Construction Commission |

| Exercise of examination powers | Fair Work Act 2009 | Fair Work Ombudsman |

| Function | Number of inspections |

|---|---|

| Inspection of telecommunications interception records under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 | 6 |

| Inspection of stored communications—preservation and access records under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979 | 10 |

| Inspection of telecommunications data records under the Telecommunications (Interceptions and Access) Act 1979 | 10 |

| Inspection of the use of surveillance devices under the Surveillance Devices Act 2004 | 3 |

| Inspection of controlled operations conducted under Part IAB of the Crimes Act 1914 | 3 |

| Total | 32 |

| Function | Number of reviews |

|---|---|

| Review of Fair Work Ombudsman use of its coercive examination powers under the Fair Work Act 2009. | 2 |

| Review of the Australian Building and Construction Commission's use of coercive examination powers under the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016 | 4 |

| Australian Federal Police's administration of Part V of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979 | 1 |

| Total | 7 |

Our approach

Our Office values independence, fairness and transparency. These values inform the way we conduct inspections and reviews and how we engage with the agencies.

We give notice to agencies of our intention to conduct an inspection and provide them with a broad outline of the criteria against which we assess compliance. We encourage agencies to voluntarily disclose any instances of non-compliance to our Office, including any remedial action they have taken.

For each of these inspection and review functions, we have established methodologies we consistently apply across all agencies. These methodologies comprise of test plans, risk registers and checklists. These methodologies are based on legislative requirements and best practice standards, ensuring the integrity of each inspection and review. It is our practice to regularly review our methodologies to reflect legislative change and ensure their effectiveness.

We focus our inspections and reviews on areas of high risk, taking into consideration the impact of non-compliance, such as unnecessary privacy intrusions. We also help agencies in ensuring compliance, through assessing agencies' policies and procedures, communicating best practices to meet compliance and engaging with agencies outside of the formal inspection or review process.

Reports

Our reports detail the extent of an agency's compliance with the legislative requirements for using certain covert, intrusive and coercive powers. We do this by assessing the extent to which agencies are able to demonstrate they have met the relevant legislative requirements.

In addition to agencies' practical compliance, we also consider their organisational culture regarding compliance. We often find that a good compliance culture results in greater levels of practical compliance.

During 2018–19 we produced 17 public reports.19

| Report | Date finalised |

|---|---|

| Quarterly report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 July to 30 September 2017 | July 2018 |

| A report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's activities in monitoring controlled operations under s 15HO of the Crimes Act 1914—for the period 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017 | August 2018 |

| Report to the Minister for Home Affairs on agencies' compliance with the Surveillance Devices Act 2004—for the period 1 January to 30 June 2018 | September 2018 |

| A report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's monitoring of agency access to stored communications and telecommunications data under Chapters 3 and 4 of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979—for the period 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017 | November 2018 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 712F(6) of the Fair Work Act 2009—for the period 15 September to 31 December 2017 | December 2018 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 712F(6) of the Fair Work Act 2009—for the period 1 January to 31 March 2018 | December 2018 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 712F(6) of the Fair Work Act 2009—for the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 | December 2018 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 712F(6) of the Fair Work Act 2009—for the period 1 July to 30 September 2018 | December 2018 |

| A report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's inspection of the Australian Federal Police under the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979—compliance with journalist information warrant provisions | January 2019 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 October to 31 December 2017 | February 2019 |

| Report to the Minister for Home Affairs on agencies' compliance with the Surveillance Devices Act 2004—for the period 1 July to 31 December 2018 | March 2019 |

| A report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's monitoring of agency access to stored communications and telecommunications data under Chapters 3 and 4 of the Telecommunications (Interception and Access) Act 1979—for the period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 | March 2019 |

| A report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's activities under Part V of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979—for the period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018 | May 2019 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 January to 31 March 2018 | June 2019 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 April to 30 June 2018 | June 2019 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 July to 30 September 2018 | June 2019 |

| Quarterly Report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 October to 31 December 2018 | June 2019 |

To ensure procedural fairness, reports that incorporate our inspection or review results are given to each agency for an opportunity to comment on our findings before the results are finalised. Depending on our reporting requirements, the final report is either presented to the relevant Minister20 for inclusion in their annual report or for tabling in Parliament, or forms the basis of our Office's published reports.21.

For our published reports we remove reference to any sensitive information that could undermine or compromise law enforcement activities.

Although we produced a number of reports during 2018–19, we were unable to finish one of our annual inspection reports, two quarterly review reports and a report on the activities under Part V of the Australian Federal Police Act 1979.

The following reports will be finalised early in 2019–20:

- A report on the Commonwealth Ombudsman's activities in monitoring controlled operations under s 15HO of the Crimes Act 1914—for the period 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2018.

- Our quarterly report by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 65(6) of the Building and Construction Industry (Improving Productivity) Act 2016—for the period 1 January to 31 March 2019.

- Two quarterly reports by the Commonwealth Ombudsman under s 712F(6) of the Fair Work Act 2009—for the period 1 October to 31 December 2018 and for the period 1 January to 31 March 2019.

Parliamentary Joint Committee appearances

In 2018–19 we appeared before and made submissions to the Parliamentary Joint Committee on Intelligence and Security regarding the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Bill 2018.

We briefed the Parliamentary Joint Committee on the Australian Commission for Law Enforcement Integrity (ACLEI) regarding ACLEI's controlled operations. We also briefed the Parliamentary Joint Committee for Law Enforcement regarding controlled operations by the AFP and the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC).

Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Act 2018

In December 2018 the Telecommunications and Other Legislation Amendment (Assistance and Access) Act 2018 amended, among other things, the Surveillance Devices Act. These amendments established a new intrusive power, through a new type of warrant, called a computer access warrant. It also included a new type of emergency authorisation for access to data held in computers. Amendments were implemented to address industry identified capability gaps and strengthen law enforcement agencies' ability to collect encrypted information. Our Office has oversight of the Surveillance Devices Act, including how law enforcement agencies use these computer access warrant powers.

The Assistance and Access Act also provided certain law enforcement agencies with new powers under Part 15 of the Telecommunications Act 1997 to request or require assistance from a communications provider in order to enforce the criminal law. Agencies must advise our Office if they issue a request or notice and we may inspect, and/or prepare a report about agencies' use of the industry assistance powers.

As agencies increase their use of these new intrusive powers, our Office's oversight will also increase.

Stakeholder engagement

During 2018–19, we provided advice and training to law enforcement agencies about compliance issues and best practice in compliance and complaint-handling. This included participating in, and presenting at forums and workshops held by the law enforcement community, as well as formal meetings with agencies.

In June 2019 the Office hosted the first of three forums for representatives of the 21 enforcement agencies we oversee. The forum, held in Brisbane, focused on compliance when using covert and intrusive powers. The forum was an opportunity for attendees to discuss best practices, concerns and newly legislated powers, and to obtain information about preparing for 2019–20 compliance inspections. We will hold forums in Canberra and Melbourne in July 2019.

Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

The Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment (OPCAT) is an international treaty designed to strengthen protections for people in situations where they are deprived of their liberty and potentially vulnerable to mistreatment or abuse. OPCAT was ratified by the Australian Government on 21 December 2017.

OPCAT requires signatory countries to establish domestic oversight bodies known as National Preventive Mechanisms (NPMs), which undertake a regime of preventive inspections into places of detention. Ratification of OPCAT also requires the Australian Government to accept visits from the United Nations Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (SPT), which comprises of international experts on detention and related functions.

At the time of ratification, the Australian Government made a declaration under Article 24 of OPCAT formally delaying the obligation to establish Australia's NPM for an additional three year period. The mandate allowing for in-country visits by the SPT has not been delayed.

As each government is proposed to retain authority for oversight of places of detention in their jurisdiction, Australia's NPM will be a cooperative network (the NPM network) of Commonwealth, state and territory inspectorates (NPM bodies), facilitated and coordinated by an NPM Coordinator.

The Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman is appointed as the NPM body for places of detention under the control of the Commonwealth and as the NPM Coordinator. Regulations establishing both functions came into effect from 10 April 2019.22